Imagine a courtroom. Picture those big wooden panels that line the grand hall of a traditional Crown court. The deep reds of the carpets. The judge sitting loftily on a bench, at the front, draped in black gowns, donning that full-bottomed wig. And all the lawyers surrounding you, speaking Latin and legalese, bewildering you with their words.

You have not been here before, but, suddenly, you find your life depends on your correct participation. You will have spent extra time ironing your clothes and polishing your shoes. You may have spent weeks picking out an outfit. Perhaps you already know what you would wear.

How does it feel to stand trial here? Is this somewhere you want to be? From here, how much do you think you will learn and grow? And do you think there might be a better place where you could improve yourself?

This is the metaphor we are often given for Yom Kippur. The Heavenly court and the earthly one. The trial of our souls. The God of Justice, who sits in judgement over us.

We beg for clemency:

סלח לנו – forgive us

We announce our expectation of a just verdict:

סלחתי כדברך – I have forgiven according to your plea.1

We rejoice in the judgement:

אשרי נשוי פשע כסוי חטאה – happy are those whose transgression is forgiven, whose sins are pardoned.2

This is the courtroom of our hearts.

C. S. Lewis, the great 20th Century English author, famed for his Chronicles of Narnia, picked up on this aspect of our thinking. When he wasn’t writing beloved children’s novels, Lewis dabbled in biblical studies as a lay Anglican theologian.

C. S. Lewis writes: “The ancient Jews, like [Christians], think of God’s judgement in terms of an earthly court of justice. The difference is that the Christian pictures the case to be tried as a criminal case with himself in the dock; the Jew pictures it as a civil case with himself as plaintiff (sic). The one hopes for acquittal; the other for a resounding triumph with heavy damages.”3

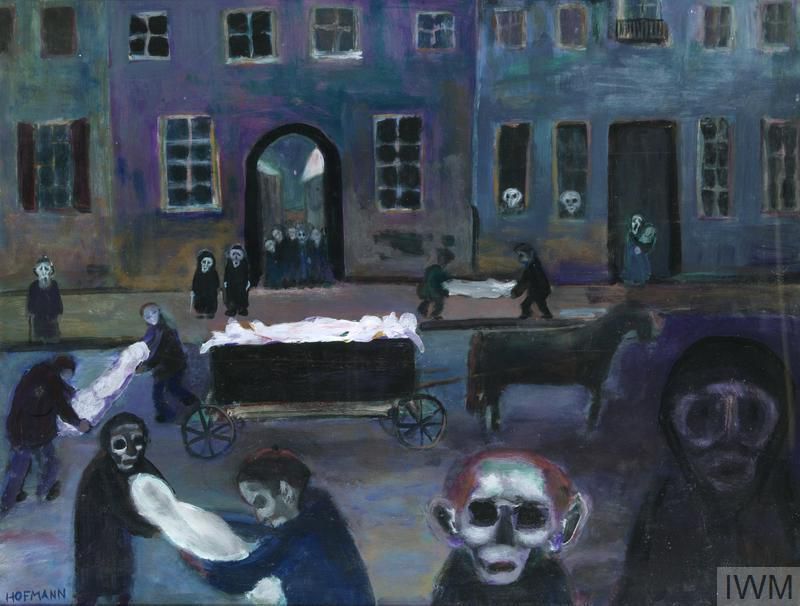

Now, Lewis is no antisemite. In fact, he repudiated the hatred of Jews, long before it became fashionable to do so.4 He is eager to point out that, at his time of writing, immediately after the Second World War, the Christian had much to atone for, and the Jew had much to charge against God.

In many ways, he has us down. We do indeed take this as an opportunity to bring all our charges against God, and to vent our grievances against the injustice of the universe. Lewis is talking about ancient Israelite religion; the religion of Scripture.

Lewis would, I’m sure, willingly acknowledge that we modern Jews also share much in common with modern Christians, in terms of our admissions of guilt and prayers for pardon.

C. S. Lewis has astutely picked up that we see all this as a trial.

But where he errs, I think, is in his understanding of what an ancient Jewish court was. The tribunal of our ancestors looked nothing like the judge’s dock of today.

A metaphor that worked so well for poets and liturgists many centuries ago can become quite damaging when it is used with the projection of our criminal justice system.

Where today, a court can dole out sentences of imprisonment, the goal of the ancient court was about restitution and social harmony.

Where today, the court expects to find a person innocent or guilty, the ancient court sought to make sure everyone felt like they had a place in their community.

The focus of our sacred writings is to create a society based on compassion, community accountability, and healing.

When we rethink what justice looked like for the authors of our Torah, concepts of trials, pardons, and sentences start to look very different. By seeing the court through ancient eyes, we can re-imagine the trial as a process of growth and healing.

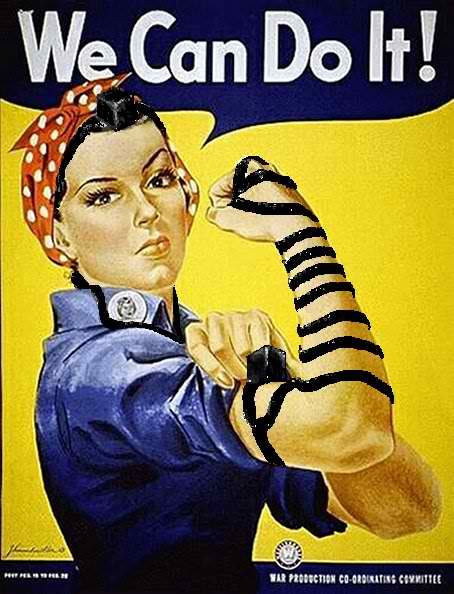

We get mere glimpses of what the earliest courts might have been. In the book of Judges, the archetypal ideal of the judge is Deborah, the prophetess. Her court is a base underneath palm trees in the hill country. We receive an image of her sitting there, while Israelites come up to have their disputes decided.5 Her court was one where people came to negotiate and be heard, but there is no indication they came to be punished. This was in the time of the Judges, the earliest of Israelite civilisations.

Later, however, ancient Israel developed a class system and a monarchy. With a state system came power and punishments. In the book of Samuel, King David pursues after the city of Avel Beit-Maacah, threatening capital punishment against everyone who rebels against him. Here, an unnamed elder-woman comes out. She admonishes the general, saying: “we are among the peaceful and faithful of Israel, will you destroy God’s inheritance?” She rebukes them with a reminder of the old system – that, before there were kings, people used to come and talk out their issues in the city. The generals agree to spare the city, providing they can enact punishment against one ringleader.6

From these two stories, we can garner an insight into what justice may have looked like in the earliest part of the biblical period. The first thing we notice is that women were leaders. This, then, may be a justice system from before patriarchal power was cemented. We also do not detect any hint of crime and punishment. Instead, the courts seem more like public cafes, where experienced negotiators help community members talk through their problems. If this is correct, we are looking at a very different type of court.

Still, courts did develop in ancient Israel, but not like those of today, nor even of the surrounding empires. In our narratives, most of the times that characters are imprisoned, it is outside of the Land of Israel, by a Pagan power, and unjustly.

Joseph is sent to prison in Egypt on trumped-up charges without any due process.7 Samson the warrior is sent to toil at grinding grain in the jailhouse by the Philistines, not because he has done anything wrong, but as a prisoner of war.8 When the Babylonian rulers send Daniel to the Lion’s Den, it is because of xenophobic laws that stop him practising Judaism.9

Our Scripture treats prisons as something foreign, where good people are sent for bad reasons.

Even when we do see examples of prisons in Israel, they are always treated by the Torah’s authors with contempt. Three of our prophets are sent to prison: Jeremiah;10 Micaiah;11 and Hanani.12 In every single case, this is a monarch warehousing a prophet because they are speaking truth to power. In the Torah’s view of justice, it is hard to see how prisons could have any meaningful role at all.

That does not mean this was a world without punishment. Scripture presents exile, flogging, and even death as options for what might constitute justice in the ancient world.13

Yet, based on our commentaries and traditions, we have the impression that such penalties were implemented only in the most egregious cases. What somebody had to do was so heinous that the death penalty would almost never actually occur.14

In the Mishnah, we read, the court that puts to death one person in seven years is bloodthirsty. Rabbi Eleazar Ben Azariah takes it even further, saying, ‘One person in seventy years.’ Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Akiva say, ‘If we had been in the Sanhedrin, no one would have ever been put to death.’15

What kind of justice system was this then? No prisons, no death penalty? No patriarchy, no punishments?

The ancient court sounds more like people just sitting around having a chat.

What if it were? What if, instead of biblical justice being all about burning and smiting, it was mostly about negotiating and feeling? How would that change how we look at our tradition? How would it change how we approach our relationship with God?

Perhaps I am over-egging how different the biblical court was. If so, bear with me.

I am well aware of how terrible some of the Torah’s punishments were. I am also conscious that what I am describing is so outside of our reality as to make it feel fictitious. If the world of restorative justice I am describing never really existed, please at least indulge me in entertaining the possibility that it could.

We are not, in this room, coming up with a proposal for how to govern Britain. We are just asking what metaphors work when we think about how to hold our own hearts on Yom Kippur. For me, the metaphor of court cases has proven really problematic, and I am looking to explore new ones with you.

The problem of the courtroom metaphor initially struck me quite suddenly. I was talking with my therapist about an issue that I felt kept coming up in my own behaviours. I said: “I’ve got another case to talk about…”

He looked around the room and said “you know you’re not on trial here, right?”

I think I had expected, on some level, that, through counselling, I could be acquitted or found guilty for all my past deeds and thought patterns.

I had built a prison in my own heart, to which I could sentence the parts of myself I liked least. I had conjured up a jury in my head, who would judge all my actions, according to the standards I had set myself. According to the standards I imagined God has set for me.

What was I doing? The point of therapy is not punishment or exoneration. It’s to learn and grow, and find ways of being better in the life I actually have. The point is not to condemn or discard my negative traits or past mistakes. The point is to work towards loving all of myself and learning from all I have done.

Perhaps you can relate to this. Have you imagined how you might punish others, or cast them into our prison in your heart? Maybe you even seek to punish people or get them out of your life. Maybe you, too, have hoped there were parts of yourself you could lock away.

We cannot apply the carceral system to our spirit. When we are doing wrong or feeling guilty, we must be free to look ourselves in the eye, and change willingly.

Is this not what God wants from us, after all? That we make amends, grow, become better. That we embrace ourselves and each other. That we turn from our ways and live.

If, then, we are in a court with God, we should make it one where we are in conversation with a loving elder, not facing a law lord who seeks to punish and acquit.

So, let us imagine a new court. It is not the court we thought into existence at the start of this sermon. It is a very ancient one, where our ancestors went thousands of years ago. Deborah’s court.

You are in the dusty scrubland of Canaan, and a few yards away you can see an oasis. People are gathering around it to fetch water. They are laughing and catching up and telling stories. They are feeding their livestock: sheep, goats, donkeys, camels.

At the edge of this well is a row of palm trees, and the tribal leaders sit, drinking sweet tea. You cannot go to prison. There is no prison. You cannot be acquitted, because nobody thinks you are guilty. You are just a person, a member of the community, looking for a way through a problem. The goal will be to find a solution that benefits everyone, and that sees maximum spiritual growth.

When you come away from this court, you can say “happy is the one whose sin is forgiven.” You don’t mean that you are relieved because you thought you were in trouble. You mean you are jubilant, because you are at peace with yourself, your community, and your God.

Let this be your court. Let this be the place you take your heart over Yom Kippur.

Come before God, not as a claimant nor a defendant, but as a congregant, seeking growth.

And thank God that there is no prison in your heart; only an opportunity for ongoing healing and change.

May this be where we judge ourselves. May this be where we judge others.

And let us say: amen.

- Birkat Selichot ↩︎

- Psalms 32:1 ↩︎

- CS Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms ↩︎

- PH Brazier, A Hebraic Inkling: C. S. Lewis on Judaism and the Jews ↩︎

- Judges 4:5 ↩︎

- II Samuel 20 ↩︎

- Genesis 28 ↩︎

- Judges 16 ↩︎

- Daniel 6 ↩︎

- Jeremiah 37 ↩︎

- I Kings 19 ↩︎

- II Chronicles 16 ↩︎

- Ezra 7:25-26 ↩︎

- eg. BT Sanhedrin 71a ↩︎

- M Makkot 1:10 ↩︎