Every day, we pray for the right kind of rain.

The Amidah praises God’s holiness and dominion over the natural world.

We change how we address God in rhythm with the seasons. In the summer, we thank God for making dew descend. in the winter, for bringing on heavy rains.

For us living in cities, we can feel quite disconnected from how important this water cycle is. I only catch snippets of how it causes concern. A radio broadcast says British farmers are worried that there hasn’t been enough frost in January. In a supermarket, a cashier tells me there is a shortage of aubergines because there wasn’t enough rain in Portugal this year.

The cycle of the right rains affects whether we have enough to eat. It can mean the difference between living safely and losing everything. There is a reason the greatest catastrophe our ancestors could imagine was a flood.

This week, we gained a sense of how important and delicate the rain cycle is.

At the start of the week, I was heading back from a holiday in the Lake District. It was searing hot. The hottest summer we’ve ever had, people kept saying. As I climbed mountains, normally soft moss felt like dry straw under my hands. The shops had stopped selling barbecues and matches.

Everyone said that the slightest spark could set the whole forest on fire. We would wind up like California or the Amazon, with acres burnt to a crisp. Thankfully, it didn’t happen, but I left with an awareness of the forests’ fragility and a deep concern that England was not ready for climate catastrophe.

Only days later, I came back to intense flooding. The rains fell intensely, relentlessly. I thanked God that I was safe inside as the skies turned black and stayed that way for what seemed like days. The area around our synagogue was drenched. Charlie Brown’s roundabout flooded again. Some in this community saw damage to their property. Members of our synagogue were displaced: moved initially to the higher floor of the care home, then relocated.

I was taken aback by how well our care team took to handling the crisis. Claire, Sue, Debz and others made sure everyone who might be affected received calls, and that anyone who needed help got it. They showed the very best of what this synagogue is for.

But I was most impressed by the bnei mitzvah students I met this week. Jacob and Layla, twins, are preparing to come of age around Pesach, at the time when we stop praying for heavy winter rains and start celebrating the gentle dew. I asked them what they want to be when they grow up. Jacob wants to be a primary school teacher. Layla says she wants to be an environmental activist.

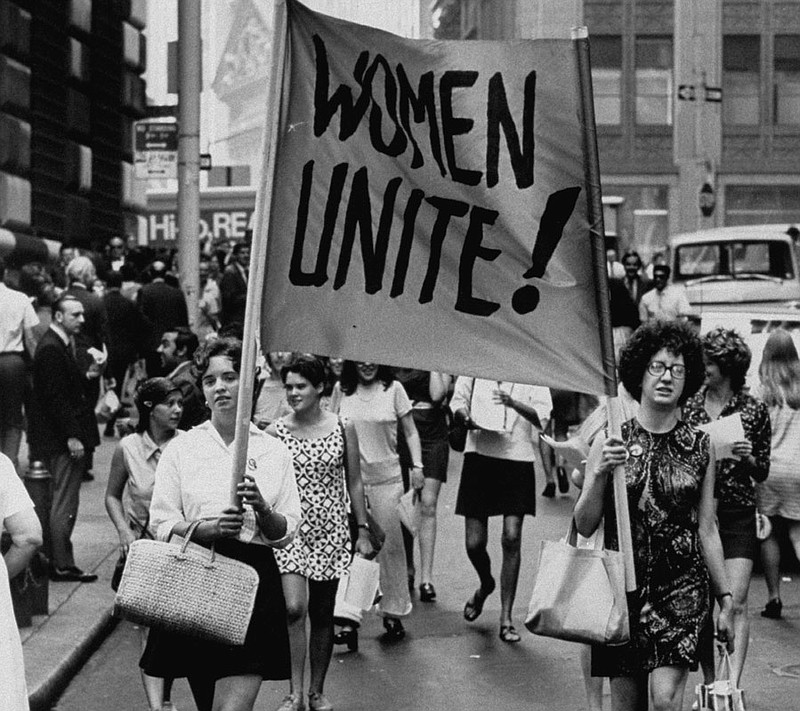

I have to be honest. When I was Layla’s age, I had no idea campaigning could be a job. It is a testament to her curiosity and sense of justice that she has found this out.

But it is also a wake-up call of how dire things are with our environment that Layla has to think of this job. The problems we saw this week had many causes. We have a rapidly changing climate. Companies have over-consumed fossil fuels and spoiled the ecosystem. Developers have built on flood plains. Much of the development after the Olympics destroyed natural wetlands, worsening the situation. But all of these factors share a common problem: we have taken nature for granted.

In this week’s parashah, we read:

If you listen, if you truly pay attention, the Eternal One your God will grant the right rains at the right times: autumn rain for autumn and spring rain for spring. You will be able to eat and so will your cattle.

But you must guard yourself against a straying heart. If you serve other gods and bow down to them, God’s anger will blaze out against you. God will shut up the sky. There will be no rain.

This text might feel familiar. It is the second paragraph of the Shema, found on page 214 in your siddur for the Shabbat morning service. You may have read it before, but it’s unlikely you’ll have heard it read aloud in any service.

It is the custom of this synagogue, and of all Reform synagogues, to read these verses in silence. So, why do we whisper it?

One reason is that we are very uncomfortable with what is implied theologically here. It suggests that good things happen to good people and bad things to bad people. We know this isn’t true. The righteous suffer and the wicked prosper. Our rabbis knew long ago that there is no individual reward for good deeds in this life. So we won’t say it out loud when we have doubts about it.

But what if it is true? The warnings in these verses are not about how God might deal with individuals, but the impact of actions on entire groups of people. If you don’t pay attention to the ethics of Torah, you all can be destroyed. If you worship gods other than the Source of all creation, you will find yourself helpless before the forces of nature. Cause and effect. Action and consequence.

In the biblical world, worshipping other gods meant turning to material things. Whereas the idol-worshippers bowed down to wood and stone, what marked out the ancient Israelites was that they only prayed to the transcendental God, who held all of nature in balance.

And that is what is happening in our world today. We are disregarding our ethical obligations to care for the planet, and we are seeing what happens. People have substituted the Eternal God for the material elilim of oil and gas. We have traded humility before nature for the arrogant belief that we can control and manipulate our environment without consequences.

Now we are living the impact. We are dealing with the wrong rains. We are witnessing floods here, in China, in Germany, in New York, and in India.

The Torah warns us: “Do not believe you have made all this with your own hands!”

We may have built cities and roads and bombs and planes, but we didn’t make the grass grow. We haven’t made the sun shine. It’s not us that makes the rains fall.

All that is in the hands of a supreme Creator, who has charged us with protecting and sustaining this planet. We must hear, and truly pay attention, to that God, whose Word calls to us today. We must take up the challenge of replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy; of rebuilding our world in harmony with nature, rather than against it; of tackling carbon emissions and climate disaster. We must enable Layla to inherit a living planet so that she actually has something to protect.

We must act now.

Shabbat shalom.

This sermon is for South West Essex and Settlement Reform Synagogue, 31 July, Parashat Eikev