Everything hangs in the balance.

Rosh Hashanah is a moment when all judgement is suspended. The scales are suspended, and the weights could fall either way.

At this moment, anything can happen. We reflect on how precarious life is, and how delicately all is held together.

In the light of Rosh Hashanah, our own lives come into focus. How fragile is our existence.

The rest of the year, we take for granted this delicate balance that allows us to go on living. Today, we notice how remarkable our lives are, and assess what we are doing with them.

Have we embraced life’s blessings and sought to make the most of our days? Have we multiplied joy and generosity in others? What were the moments we squandered or took for granted?

At Rosh Hashanah, we acknowledge our vulnerability. We listen for God’s voice within us. We hear the messages this day brings. God, in turn, hears us.

Then, we find a way to go on. We affirm our lives.

The stories of Rosh Hashanah point us to moments of precarity. We read of times when life almost did not come about, and of moments when life almost came to an end. Through these ancestral tales, we access our own vulnerability.

Hannah longs for a child to be born to her barren womb. She asks: “why do I exist?” Then, God hears her anguish, and she gives birth to a boy. His name is Samuel, meaning God hears.

Sarah laughs at the thought that she could conceive in old age, then God remembers her, hears her, and she has Isaac.

Isaac is destined to be Abraham’s heir, then Abraham takes him up to Mount Moriah to kill him.

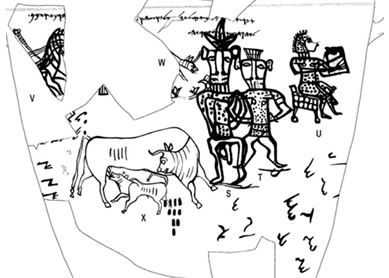

When we picture the Binding of Isaac, we can clearly see Abraham’s raised hand – slaughtering knife outstretched to the sky – ready to murder his own son. We are struck by the moment when all hangs in the balance.

Finally, God speaks, and Isaac is to be killed no more.

In all these vignettes, we find ourselves caught in stories of people whose lives are racked with precarity, but who listen out for God’s voice, take away a message, and find a way to go on that affirms life.

Interwoven with this story of the main characters, our ancestors, is another story, of people living more marginal lives. The story of Hagar and Ishmael speaks even more explicitly to life’s precarity.

In Orthodox communities, where they observe the second day of Rosh Hashanah, the story of Hagar and Ishmael is usually read today. Here, in the Liberal lectionary, wherein we follow the Israelis and hold by one day chag, we are given the option of reading either Isaac’s or Ishmael’s story.

I have opted to read the story of Ishmael because I believe it speaks most clearly to the festival’s theme of life’s uncertainty. Everything about the lives of Hagar and Ishmael is left to the hands of those more powerful than themselves.

Hagar is called a handmaid – a word that glosses over the gross crime inherent in a purchased human being.

A handmaid had no property, no income, and no family to come and redeem her. Most handmaidens were separated from their own kin, and stripped of their original language.

Hagar’s name means “the foreigner.” The Torah calls her “the Egyptian.”

She was beholden to her mistress, Sarah. Hers is the most precarious position one could have in life.

A handmaid cost more than a male servant because the handmaid could produce the most valuable good: more slaves.

Unlike the other women in our readings, Hagar does not long for a child. She expresses no desire; she offers no consent. She is simply used as a vehicle so that Sarah can have a son.

Abraham will take her as a concubine. The child will be Sarah’s property and Abraham’s heir.

This is already a dangerous situation. If she does not give birth, Hagar fails to deliver on the terms of her purchase. If she does have a child, she could become a rival to her mistress.

That is precisely what happens.

Hagar becomes pregnant, and Sarah immediately flies into a jealous rage. Hagar runs away, but has nowhere to go. She can either risk the harsh desert as a single pregnant woman, or she can return to an abusive household.

For Hagar, everything hangs in the balance. Then, God hears her and intervenes. An angel tells her that God knows her suffering, but promises that her life will get better.

She will bear a son. He will be a highwayman, attacking everyone, and attacked by everyone. His name will be Ishmael, meaning “God has heard.”

As with all our protagonists in Rosh Hashanah stories, Hagar finds her life in the balance. She realises how precarious her existence is. Then, she listens for God. Hearing God, she finds a way to move forward.

So, Hagar returns. And her life hangs in the balance once more.

This is where the Rosh Hashanah reading begins.

Here, Sarah sees Ishmael playing and demands of Abraham “cast out that slave and her child, because that son-of-a-slave will not share in the inheritance of my son Isaac.”

Abraham followed Sarah’s words, and sent Hagar out into the desert with nothing more than some bread and a skin of water.

She wandered about in the wilderness of Beersheva until they had completely exhausted her water.

We are told that Hagar sat an arrow-shot away from Ishmael.

This language seems to make us consider Hagar’s own thoughts: in this moment, Hagar thinks: “maybe I could put the boy out of his misery.” But she cannot do it. She cries out “I do not want to see the child die” and bursts into tears.

Then God hears. God hears Ishmael’s voice crying out, and sends forth an angel from Heaven.

Every bit of hope was lost. Everything hung in the balance. But Hagar listened. And God listened. And they heard each other. And Hagar found a way to go on.

The angel says: “כִּי שָׁמַע אֱלֹהִים אֶל קוֹל הַנַּעַר בַּאֲשֶׁר הוּא שָׁם” – “for God has heard the voice of the boy where he is.”

In the Talmud’s treatise on Rosh Hashanah, this is the hook our rabbis use to tell us about our own place before God.

The rabbis say this means that God hears Ishmael in the moment when he cries out.

To God, Ishmael’s past and future actions matter not.

God does not care that Ishmael comes from the lowest and most vulnerable place within Israelite society. God does not care about the prediction that Ishmael will go on to be a highwayman. All that matters is that Ishmael cries out at that moment.

This, says the Talmud, is how we should all see ourselves on Rosh Hashanah. Rabbi Yitzhak declares “every person is only judged according to their deeds at their moment of trial.”

We are only judged by our hearts in this moment of reflection.

We are not our past mistakes, nor our future errors. We are the people that God beholds today. We are the people who chose to turn up, on this Rosh Hashanah, who knew we wanted to engage with our own souls.

That is all that God sees.

This is a part of the Talmud’s more general argument about Rosh Hashanah, that it is a time when everything hangs in the balance.

Our rabbis teach that we should all imagine that the whole world is finely balanced between good and evil, and that it is our responsibility to tip the scales.

Moreover, say the rabbis, our own hearts are precariously weighted, with an even chance of falling to the side of good or evil. In this analysis, then, the fate of the whole world can rest on just how we direct our own hearts.

So, we need to take every opportunity to place a greater load on the scale of good.

The Talmud offers things we can do to make such a change: give to charity, call out in prayer, and change our behaviour. Any one of these actions can cause a shift in that delicate balance.

A small prayer, a slight modification to how we act, a donation to a righteous cause – any of these can transform everything.

We live in a time when all can feel uncertain. Life seems nerve-wracking. At times, it does indeed feel like the balance of all the scales in the world is tilting ever more toward evil.

The Talmud tells us that we still have some control. We can still be a force for good. We can still nudge the fine weightbridge an inch towards goodness.

The Torah gives us examples of people whose own lives hung in the balance. They listened for God, and God listened for them. And God answered “I have heard you where you are.”

So, if you feel like you are hanging in the balance, hang on in there.

God is hanging in there with you.

Shanah tovah.