Before the Enlightenment, the world was governed by unknowable spirits and invisible entities.

There was so much we did not know.

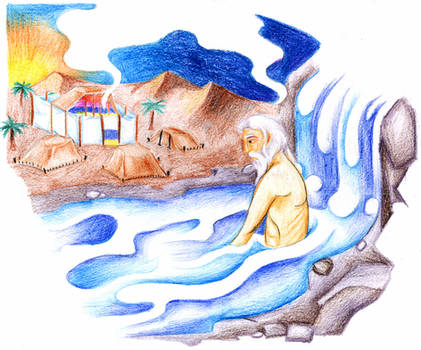

If your farm didn’t produce any crops or the skies did not give you enough rain, you did not have modern technology to inform you about drought predictions for the next three years. You would have no way to know that the water coming from your clouds was directly connected to oceans miles away.

But you had your priests, and your rituals, and your superstitions. You had small gods in the hill country to which you offered libations. And, so far, when you had upheld your traditions, the rain came as it was supposed to.

When you got sick with a skin infection, you could not see a GP who would consult a modern medicine manual and give you a cream that would clear it up in just a few days. You would not have knowledge about germs, allergies, and viruses.

But you had your priests, and your rituals, and your superstitions. You had your rules governing sin and repentance. You had reliable experience that bodily suffering could be healed by atonement. And, so far, when you had upheld your traditions, the rain came as it was supposed to.

Please hold this in mind as we read this week’s Torah portion.

It may be easy for a modern mind, after the Enlightenment, to scoff at the strange priests, rituals, and superstitions that govern these chapters in the Book of Leviticus.

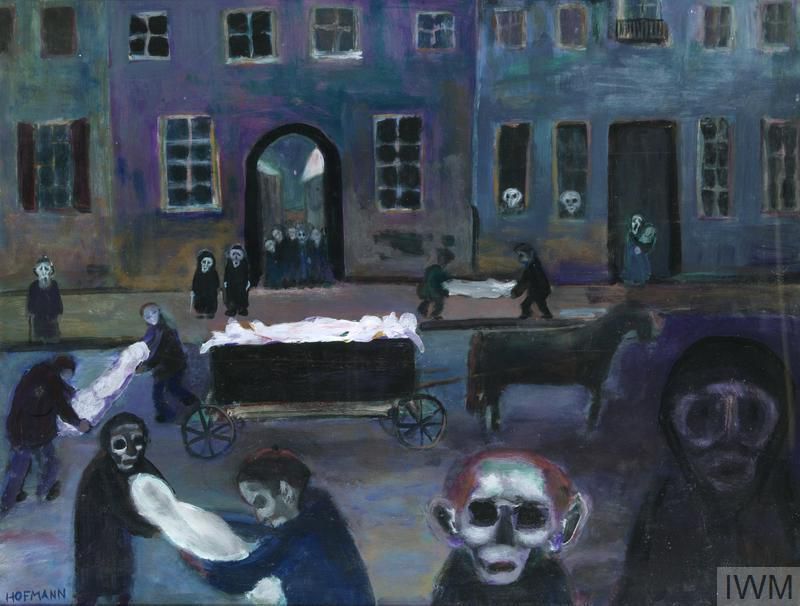

You might feel slightly embarrassed to imagine the rites our ancestors slit open goats, threw their entrails around and burned them for days until they stunk out a tent as expiation for their sins.

You might squirm at the vivid descriptions of cotton-clad priests flailing around the limbs of slaughtered cattle to win the favour of their god.

It may even seem primitive how they delight at the animal fat creating explosive fire, which they see as evidence of their god’s approval.

But they were doing what they could with what they knew. And they were engaging earnestly with what they did not know. Beyond the world they experienced was an unfathomable mystery, and they wanted to draw closer to it.

Indeed, only verses later, we get an insight into their own feelings of inadequacy. We get a real sense that they knew how much they did not know.

Nadav and Abihu do absolutely everything right. They follow the priests, carry out the rituals, and trust in the superstitions. They are formally inducted into all the correct practices by their father, Aaron the High Priest.

They do everything right. And then they die.

The burning animal fat explodes in a blaze that kills them both.

How can our ancestors make sense of this?

Our Torah gives two answers. The first is from Moses. Moses recalls a prophecy when God said: “Among those who approach me I will be proved holy; in the sight of all the people I will be honored.’”

We may interpret this as a way of Moses defending God. Moses is saying: while this may feel like a violation of our belief system, it is in fact proof of it. Holiness is a very dangerous quality.

God has demonstrated how sacred it is to engage in the rituals. God has shown what honour and risk are involved in holy service.

So, for Moses, this sudden death of their priests does not undermine their belief system. It’s just evidence of how little they understand about their sacred rituals. In the fire, they have reached the limits of their knowledge.

Aaron, too, offers an answer. Silence.

We may interpret Aaron’s unspoken response variously. We may read into it horror, resignation, anger, acceptance, or solemnity.

But regardless of what he was feeling, we see that Aaron has no intellectual answer to the problem. He neither agrees nor disagrees with Moses. Aaron finds the limits of speech. He finds the boundaries of what he can even express.

Moses and Aaron lived in a world of unknowable spirits, governed by superstition. They made sense of their confusing world through priests and sacrifices. And no matter how well they constructed their rituals, they still found their limits.

There were things they did not know.

But we live in an era after such theologies. From the 17th Century onwards, Western Europe was gripped by a profound truth.

As the people challenged the unlimited power of the established church, philosophers pulled apart the stories religions had told.

This was the Enlightenment.

No more would they be hoodwinked by magical thinking or damned by promises of divine retribution. Everything, every idea, would be subjected to ruthless scrutiny. The greats of these generations would challenge the tenets of even science itself.

We live now in a world formed by their ideas. While our ancestors were beholden to talismans, omens, and sacrificial fire, we have evolved to hold modern ideals of truth and rational enquiry.

So, why hasn’t religion disappeared?

Isn’t that the obvious next question?

We have rid ourselves of superstitions, but synagogues are stronger than ever. Most of the world is still deeply religious. Despite constant predictions of its demise, faith remains stronger than ever.

For those who wish to understand God’s persistence after the Enlightenment, they may want to look to Immanuel Kant.

Kant was the last of the Enlightenment thinkers. His impact on this period of intellectual history was so great that some even date its end to his death.

Kant was a profound writer on truth, ethics, the scientific method, and what we can really know. He was also a devout Christian.

Kant was animated by the same questions that bothered our ancestors who witnessed Nadav and Abihu die.

He was not confused about why burning fat could cause a blaze, or why religious rituals didn’t always yield the same results. Those were the questions of the past.

The question still lingered, however: why does it seem like there is no justice in the world? Why do bad things happen to good people, and why do the wicked seem to get away with it? Why, no matter what happens, does evil seem to persist?

In his essay, The Miscarriage of All, Kant says he will put God’s justice before the trial of reason. Kant contemplates all the possible answers.

Maybe what we think is evil isn’t really. Maybe the world works in ways we don’t understand so that evil has to be permitted. Maybe there are other forces in the world beyond God’s goodness.

And Kant gives us an answer, which is… we don’t know.

All of these explanations only expose the limits of our understanding.

None of the answers anybody has come up with is satisfactory.

We are finite beings trying to understand Infinite Truth.

And still, says Kant, we retain our faith.

For Kant, none of these questions undermine the existence of God’s justice. They just show what we do not know.

So, perhaps we need to approach these stories with more humility and less contempt.

The ancient priests may well have splashed ox blood around an altar to ward off sin, but we are no closer to answering the questions that motivated their rituals.

We are barely separated from them by any time at all.

We are still just animals, scrambling in the dark, trying to make sense of our world.

And we still need each other, with all our beliefs and rituals, to get through this life that can seem so unjust.

We are each other’s guides through a mystery we may never resolve.

We need to be humble about what we do not know.