“Hineni he’ani mi-ma’as – behold, I am poor in deeds and lacking in merit. Nevertheless, I come trembling in the presence of You, O God, to plead on behalf of Your people Israel who sent me, although I am neither fit nor worthy of the task. You who examine hearts, be my guide, and accept my prayer. Treat these words as if they were spoken by one more righteous than me. For you listen to prayers and delight in repentance. Blessed are You, O God, who hears our prayers.”

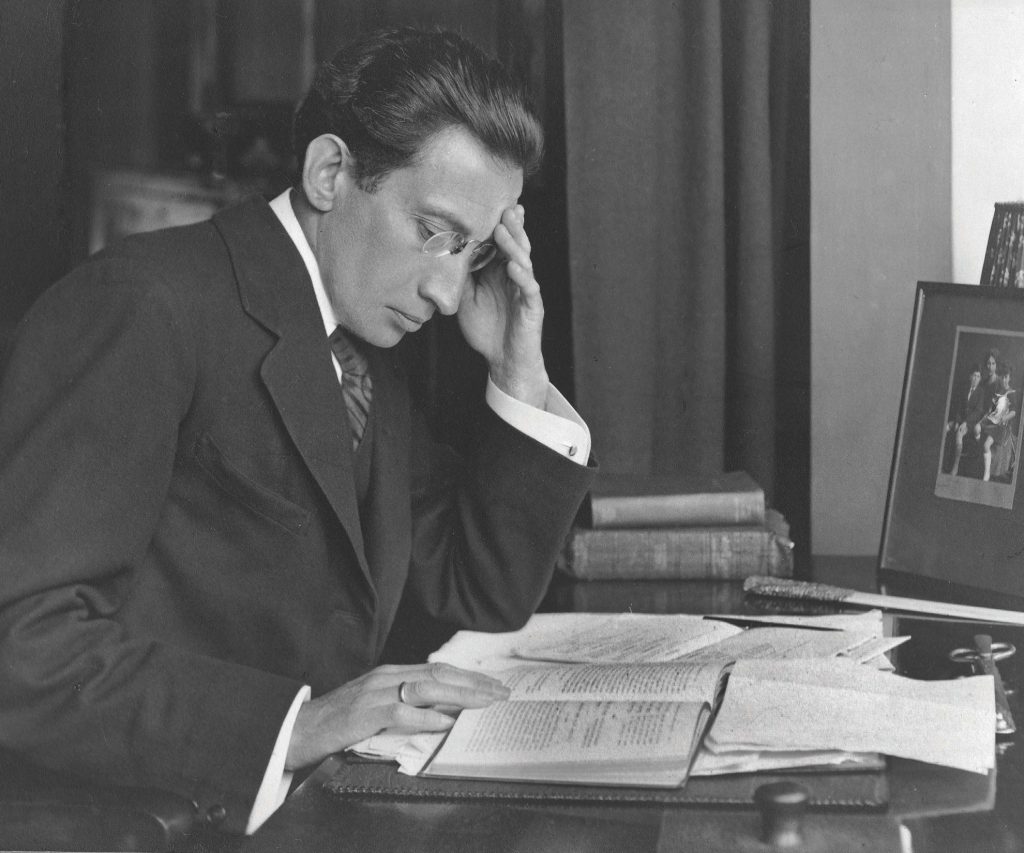

In the synagogues of medieval Europe, the service leader used to begin with this public prayer of atonement, openly acknowledging their own inadequacy.

In the Liberal world, we have been shaped by the Victorian attitude that eschewed public vulnerability. So, instead, this prayer is given out to rabbis to read privately to themselves.

The days when we had to pretend to be perfectly put-together are over. In our age, we recognise that openly sharing our insecurities builds a more emotionally authentic culture, where people are better at handling their feelings.

So, this year, I not only quietly recite this prayer in my office, but share it with you openly.

This year, these words feel more profound than usual.

This is a sensitive time, and I know how fragile so many hearts are.

In the build-up to these Days of Repentance, an American Masorti rabbi, Joshua Gruenberg, wrote:

“Rabbis stand before their congregations with trembling hearts. We know that every word matters. We know that words can wound and words can heal. And we know that in a climate like this one, the margin for error feels impossibly thin. […] The only way we will find wholeness is if we grant each other the space to be imperfect, the courage to be vulnerable, and the grace to be human.”

As this year came to an end, I thought back on the conversations I’d had with you over my time here. I thought back over some of the pain and worry you had felt, and realised just how much stress some members of the community were feeling.

Words can, indeed, hurt and heal. They matter. I want to honour that, by reflecting on the pain some of you have expressed.

We come here because we want to be together, in our fullness, with all our wounds and trauma, so that we can move towards healing.

To that end, let’s consider how we can approach anxious and hurting people with compassion. That is, after all, what we all need from each other.

The world has changed greatly in the last few years. So much feels more precarious.

Ten thousand people rallied at Tommy Robinson’s far right march in London to a speech by Elon Musk telling the crowds to get ready for violence against immigrants. The news from Israel and Gaza, and Russia and Ukraine, and Sudan and Ethiopia, keeps rolling in, feeling ever worse.

For me – and I know for some of you – the horrors of October 7th and the ensuing assault on Gaza marked a major turning point. In many of us, these events have brought up trauma responses we didn’t even know we had.

Since then, so much has unfolded that is out of our hands. This can feel painful when your instinct is to find solutions and assume control.

We have to accept our own limitations. I sometimes recite to myself the Serenity Prayer: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Those of us within this room do not have the power to bring about peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians. We cannot get the hostages back or stop the starvation of Gaza.

That feels hard. If it were up to the members of this synagogue I have no doubt that the whole world could live in peace.

I am certain that we could indeed solve the country’s problems and fix our hurting planet. But nobody seems to be letting us do that, outside of setting the world to rights over kiddush.

But that does not mean we have no power at all.

The one area where we have real power is in our own homes and our own community.

And, there, we have the power to decide how much compassion we feel.

Even in the face of our own trauma and fear, we can choose to feel compassion for others.

Perhaps you can relate: in the immediate aftermath of October 7th, I felt intensely isolated. I felt a void where compassion ought to be.

I felt, among Jews, my own people, that I struggled to find many people who felt compassion for the people in Gaza.

On the left, as much my natural home as the synagogue, I struggled to find many people who felt compassion for Israelis.

Initially, I narrowed my circle to a small niche of Progressive Jews with left-wing opinions. It was comfortable and reassuring, when what I needed was to feel safe.

But if I was looking for compassion in the world, I needed to bring it into the world. I needed to model it.

Not just with the people who I knew felt like I did, but also with those whom I assumed were miles away from me.

It is easy to love humanity in general, and fine to pity people on TV. It is much harder to love the people nearest you when you feel so distant, or to understand them when it feels like they are living in a different world.

How could I look for compassion elsewhere if it wasn’t in my own heart?

How can we look for compassion if we do not feel it?

You can’t expect others to extend compassion to strangers when you can’t even have conversations with the people you already know.

I felt then – I still feel – that, perhaps, if we can feel compassion in our synagogues, and extend it out towards the world, and that others could extend their compassion too, then it might cause something to shift.

And, ultimately, that shift might make this world, which is harsh and unkind, a little better than it has been.

The message of compassion is already explicit in the liturgy of our Yom Kippur service.

God’s name is Compassion.

We read the refrain that repeats throughout the High Holy Days: “Adonai, adonai, el rachum vechanun… a God compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in compassion and faithfulness…”

It is a beautiful invocation of God’s qualities to help us through Yom Kippur.

The verses come from Moses’s second acsent of Mount Sinai, when he takes the new set of the Ten Commandments in his hand. As Moses walks down the mountain, God comes with him.

As Moses chants out these declarations of God’s mercy, it is as if Moses has truly understood what kind of God he is dealing with.

He learns how the world really works. He sees that it is governed by compassion.

Just before coming to get the new tablets of the law, Moses had seen the Israelites worshipping a golden calf, and smashed up the first set of the Ten Commandments.

These are great sins: idol worship and wanton destruction are strictly prohibited. The Israelites have been wayward. Moses has been angry.

Still, God, abounding in compassion and faithfulness, says: “Try it again. Have another go.”

In the Talmud, Rabbi Yohanan teaches that whenever the Jewish people sin, they should think back to this verse.

In the repetition of “Adonai, Adonai,” the Jews should understand that God is their Loving Creator before a person sins, and God is their Loving Creator after a person sins and performs repentance.

God is always willing to give people another chance.

In the same section of Talmud, we learn that, in the moment when Moses recited those words, God made a covenant based on thirteen attributes of mercy. It was a promise that God would always hear our prayers.

Later, in the Middle Ages, the French commentator Rashi elucidated what these thirteen attributes were.

In each word, says Rashi, is a reflection of the type of compassion God feels.

God is slow to anger to give you a chance to repent.

God is abundant in mercy, even with those who don’t deserve it.

God remembers good deeds even for a thousand years.

Even when we hear that God holds grudges for three and four generations, Rashi says that this only refers to people who maintain the evil ways of their ancestors. If they repent, all can be forgiven of them too.

This is how one truly maximises compassion.

So, let us be compassionate.

Let us maximise how much compassion we feel.

Our own community and our own homes are small places where we can truly practise compassion in a world where it seems so sorely lacking.

Last week, in her Rosh Hashanah address, Rabbi Angela Buchdahl, of the American Reform movement’s flagship synagogue in New York, reflected on how the division in the world was creating strife even within her synagogue.

She urged her congregation to practise compassion, saying:

“It now seems that any expression of compassion for “the other side” is regarded with suspicion – as disloyal, or even threatening. Is our capacity for empathy so finite? Are our hearts so small, that if we increase our empathy for certain people, that we need to reduce it for others — until one day, we conclude: that ‘other side’ is not deserving of any compassion?”

Here, the “other side” could be so many different groups in this increasingly polarised and hostile world.

We all want to feel like people understand our own side, but struggle to extend our understanding the other way.

You don’t have to agree with people to love them. You just have to be curious, and try to understand them.

Some days, we may be capable of less compassion than others. On those days, let’s give ourselves grace, take time out, and remember how flawed we all are.

Even on our worst days, we can always try to understand each other. We can hold our own hearts while making them permeable enough to feel others’ pain too.

When people challenge us, let’s look for the best in them. Imagine their best intentions, and try to consider what problems they might be facing.

We are, all of us, flawed and temperamental. We all ask good grace of others, and we can all give it in return.

This year, let’s try to feel compassion for the people in our own families and homes.

Let’s try to find compassion for the people in our neighbourhoods. Perhaps we will shift something in them.

Let’s find compassion for the people in our community, so that we can hold each other, in our diversity, through these trying times.

And, as much as we can, let’s try to find compassion for everyone.

It won’t change the news cycle, but it might change you. And you might change others.

It is a small contribution to this world, but it is a mighty one.

It is the best that we can do.

Behold, I am poor in deeds and lacking in merit. Nevertheless, I come trembling in the presence of the One who hears the prayers of Israel. O God, You listen to prayers and delight in repentance. Blessed are You, O God, who hears our prayers.

Amen.

Kol Nidrei 5786, Kingston Liberal Synagogue