In the distant past, people made small gods. They carved out wooden statuettes to represent fertility, or hewed rocks into the shapes of animals that would bring them good luck. They made depictions of stars and planets, which would help them in their daily struggles. The ancients looked after the gods – giving them food, drink, rest, and clothes. In return, their little talismans looked after them.

When Abraham was born, he lived among the idol worshippers of Ur. He had no teacher nor guide, but came to understand, through his own reasoning, that God was the only Creator of all things, and that the world was governed by an invisible Force that could not be depicted. The totems people served were not gods at all, and could have no impact on the world.

As a result, he went around smashing up and destroying every idol and household God he could find. He went around telling everyone that the worship of idols was a great lie, and that the One True God would destroy anyone who bowed down to them. He enjoined his followers, the descendants of Abraham, that they, too, must destroy all idols.

This poses a question: what is so bad about idol worship?

If these are just empty vessels, why fear them? If they are not really gods, what harm can they do? Why should idols be so concerning that we must smash them up everywhere we find them?

By the time we get to the end of Moses’s life, here in the Book of Deuteronomy, the aversion to idol worship is even more intense.

At the start of Re’eh, Moses instructs the Israelites to find every idol, tear down the pillars, smash up the altars, cut down their gods, and destroy any memory that these false gods ever lived there.

If a seer comes to you, says Moses, and they say they have had a vision that you should worship idols, you must kill them instantly. You must purge them and their evil words.

If your own brother, sister, mother, father, or friend wants you to worship idols, Moses says, show them no pity. Don’t try to stop anyone from killing them. In fact, make sure it is your own hand that strikes them down.

And if you find out that there is a town where people worship idols, go and kill everyone in it. Bring everyone from the town together and slaughter them. Bring everything from that town into the square and burn it to the ground. Destroy that city in its entirety and never let anybody rebuild it.

This feels like something of an over-reaction.

How can idol worship be so bad that it is worse than murder, worse than cutting off your own kin, worse even than razing a city to the ground? Why should this practice of building little statues be so intimidating that it requires such destruction?

This feels completely out of place with our moral sensibilities. That’s not just a modern thing.

Even in the 13th Century, rabbis were worried about this injunction. Rambam, the great rabbinic decisor who codified all of the Torah’s laws, was also concerned.

Rambam lived among Muslims and Christians in medieval Egypt. He admired and appreciated them. He read the works of the great Greeks who had never known monotheism, like Plato and Aristotle. He found them wise and inspiring. He was deeply opposed to fundamentalism and chauvinism. Rambam, like us, was not really up for burning cities to the ground just because they did not follow our God.

Rambam says: don’t worry. The world for which these laws were written no longer exists. People don’t worship idols any more. Whatever perverse practices the Pagans once did, they are not doing them now.

Even if they did exist, we would not have the authority to burn a city to the ground like that. You would need a Sanhedrin – a court of 71 learned judges who could recite the laws in their entirety – and we have not had one of those for many centuries.

Even if the idol worshippers did still exist, and we did still have a Sanhedrin, the Sanhedrin would necessarily make sure to do everything possible to educate the idolaters away from their ill-conceived practices, help them to repent, and find ways to make sure they can live in the true religion of monotheism.

So, don’t worry, says Rambam, we can forget about all that.

But the trouble is we can’t.

It’s there in the Torah. We read it every year. Rambam still has to go and codify all these bloody edicts, that make such monsters of people who pray to fetishes.

And Rambam does not answer my fundamental question. The people who bow down to wood and stone might be wrong; their beliefs might be misplaced; but what is so bad about giving a drop of wine to a brick?

The most compelling answer I have found comes from a 20th Century psychoanalyst. Erich Fromm was born in Frankfurt, Germany, at the start of the last century. He studied psychiatry and philosophy among the greats of his generation, then moved, in 1934 to America, where he became a leading writer and critic of modern society. Needless to say, he was Jewish.

In 1976, Erich Fromm wrote a landmark book called “To Have or To Be.” This text became the cornerstone of the anti-consumerist movement.

Fromm engaged seriously with our religious texts. He saw them as inspiring people with a serious psychological message about how to live.

The difference between real worship and idolatry, says Fromm, is not what you worship, but how you do it. He calls it the “being mode” and the “having mode”.

The problem with idolatry, says Fromm, is that it makes you think God is something you can own.

Hebrew monotheism is a rejection of the entire enterprise of having a god:

“The God of the Old Testament is, first of all, a negation of idols, of gods whom one can have… The concept of God transcends itself from the very beginning. God must not have a name; no image must be made of God.”

Fromm writes:

“God, originally a symbol for the highest value that we can experience within us, becomes, in the having mode, an idol. In the prophetic concept, an idol is a thing that we ourselves make and project our own powers into, thus impoverishing ourselves. We then submit to our creation and by our submission are in touch with ourselves in an alienated form. While I can have the idol because it is a thing, by my submission to it, it, simultaneously, has me.”

So, for Fromm, idol worship isn’t over at all. In fact, it is a pitfall any of us can stumble into. If you think that faith is something you can have, rather than a way of living, you are guilty of idolatry. Fromm says:

“Faith, in the having mode, is a crutch for those who want to be certain, those who want an answer to life without daring to search for it themselves.”

Fromm goes further. It’s not just about God. It’s about everything. Do you want to be in this world, or do you want to have it? If you think you can have it, you will never be satisfied. But if you can truly be in it, you will find no need to have any desires met. Fromm says:

“The attitude inherent in consumerism is that of swallowing the whole world.”

Fromm even extends his philosophy to how we love. Do not try to have love, he warns, but try to be in love.

“To love is a productive activity. It implies caring for, knowing, responding, affirming, enjoying: the person, the tree, the painting, the idea. It means bringing to life, increasing his/her/its aliveness. It is a process, self-renewing and self-increasing.”

If we take Fromm seriously, we have a whole new way of looking at the world. Inspired by the prophets, everything we do can be about existing and loving and being. We can reject the whole ideology of possessing.

That is what is wrong with idolatry. The artefacts of the Pagans aren’t just wooden blocks. They tell us a way of living. The wrong way of living. They direct us to control and own.

Rambam may be right. The idolaters do not exist in cities any more.

Instead, today, they live in our own minds. And we must burn them down, if we are to be truly free.

Shabbat shalom.

Tag: rambam

What did Jonah do inside the whale?

A simple Jew prays to God on Yom Kippur, and says “Ribon shel olamim, ruler of the Universe, I do not have much to repent of. Not compared to you. Unlike you, O God, I have not taken away children from their parents; I have not taken away parents from their children; I have not allowed disease and starvation and war. Compared to you, Holy One, I have been a saint. So, this year, I won’t be repenting. It’s your turn to repent.”

The rabbi asks him, “what were you praying there?”

He tells her all that he’s said.

She says: “You fool! You let God off too easy. You should have told God to bring about the Redemption as well.”

I don’t know about you, but I haven’t felt much like repenting this year. After all, what have I done, compared to the enormity of wrongs perpetrated?

I haven’t killed anyone or waged any wars. I haven’t robbed anyone or embezzled any funds. To the best of my knowledge, I haven’t brazenly lied or misled. I certainly haven’t intentionally hurt anyone. I’m just not in the same league as the great sinners of our time.

And I don’t much feel like growing this year, either. Other years, I have enjoyed the stillness of Yom Kippur for reflection on being better. But I don’t feel like doing it this year.

Sure, I’m grateful for turning off my phone so I don’t have to look at all the bad news, but that’s more about self-care than self-improvement. I’m more interested in switching off from the world than in switching onto myself.

I mean, really, do I have to move? The world is changing so much, and not for the better. Shouldn’t I be allowed, as a one-off, to stop constantly evolving and just be as I am for a bit?

You know who else just wanted to stay still?

Jonah.

I think Jonah knew exactly how I am feeling now.

He was perfectly alright where he was, before God got involved and told him he needed to go and sort out all the problems of the world.

Who was Jonah in the scheme of things? He certainly was not a big player in the wrongs of the world. All of Nineveh’s sins were enormous and happening miles away. Why should he have to change himself?

So, when God called on Jonah to get up, that was already asking too much.

Jonah ran away to Tarshish. He shouted at God: “haven’t you got bigger fish to fry?”

God said: “you want to see a big fish? I’ll give you a big fish!”

One came along and swallowed him whole.

Now, all of the story before is about Jonah not wanting to move and all of the story after is about what happened after God moved him.

What happened in the whale, however, should really interest us.

This year, I feel like I’m in the whale. I am sitting in a puddle from which I feel like I cannot budge. I am stuck here and have no idea how to get out. All around me, the waves are crashing down and there’s nothing I can do to stop them.

(A pedant will point out it’s not actually a whale. Technically, it’s a big fish, and the idea of it being a whale came later. But, technically, I’m not actually inside a whale at all, I’m in a synagogue, so I’m going to stick with the idea of the whale because it feels evocative.)

Now, I’m not even on the level of Jonah. My task is not nearly as big and I am not even inside a literal whale. So Jonah should be a good starting-place for my feelings of stubbornness and obstinacy.

What did Jonah do inside that whale? He despaired. He observed. He prayed. He sang. He learnt. And, eventually, he repented and grew.

So, this Yom Kippur, let’s engage with the whale. Let’s focus just on the three days Jonah spent inside the belly. Maybe we can learn from Jonah what to do when everything feels too overwhelming but we know we have to change anyway.

The second chapter of the book of Jonah is not narrative-form, like the rest of the book. Only the first verse, where Jonah gets swallowed by the whale, and the last verse, where the whale spits Jonah back out again, follow a linear storyline.

The rest of the chapter, only eleven verses long, reads more like a poem. It is a song, where each verses contains a parallel structure. It would fit just as well in the Book of Psalms, where there are similar supplications to God.

If the second chapter of Jonah is a journey, it is only a spiritual one. Jonah himself remains completely static, stuck in the belly of the beast.

His soul, on the other hand, begins in the depths of despair, goes through questioning and defeat, recognises the glory of God, and finally comes out committed to getting out there, thanking God, making offerings, and taking part in the deliverance.

This feels like the most important chapter to us, then. We are just sitting and standing in the same space. But we are expecting our souls to move.

I am feeling stuck in a world I cannot change, but I know I have to get somewhere else spiritually. We can’t just sit around here and hope to become better people. We know it needs work. But without a narrative, how do we know what to do?

Well, in the spaces left by the absence of narrative, the rabbis come up with their own stories. Pirkei deRabbi Eliezer is a collection of creative writing, compiled over many generations, that retells the biblical stories. These are our midrash, and in this rabbinic fan-fiction, we get a story to go with everything that Jonah says.

From these stories, we might come up with our own meanings of what we should be doing here.

The first thing Jonah does is acknowledge where he is. He accepts that he is in the belly of the fish.

The midrash gives us a grandiose interpretation of what that looked like. It was like entering into the great synagogue: an enormous, echoey chamber. The fish’s eyes were two great windows, so that Jonah could see what was going on underwater. Inside the fish was a giant pearl, which illuminated the belly and shone out towards the sea. With a lamp and windows, Jonah had a clear vision of where he was.

What can we learn from this? We learn that we need to be honest with ourselves about where we are. The world is a bit of a mess right now, and there’s no point putting on a happy face and pretending everything is OK. Equally, we are pretty safe here. We in this room are not under attack, and the risk we would be is very low.

So, start by taking stock of reality. Where am I? I’m in a synagogue, sitting on a comfy chair, with my feet planted on firm ground. I can see the lights of the room and smell that familiar sweet must of this religious space.

But it’s not enough to just say where we are. We need to say how we feel. That’s what Jonah does next.

He says: “I am crying out to God from my narrow-straits, please answer me.” Jonah says, “I am crying out from the belly of Hell, may God hear my voice.”

The midrash says, that’s exactly where the whale took him. It plunged him right down into the depths and showed him the gates to Hell.

So, we need to do the same. We need to ask ourselves how we are really feeling. Be honest about the frustrations and worries and anger we feel.

Next, Jonah finds a way to relate what is going on to what has gone before. In the depths of the ocean, Jonah says, he sees the billows and waves and reeds.

According to the midrash, this is because the whale took him on a tour, not just of the sea, but of Jewish history. The whale showed Jonah the foundations of the earth, deep on the ocean-floor, and reminded him that God had made the world. The fish took him to the Sea of Reeds, and showed him the flora of the spot where the Israelites had crossed out of Egypt.

Faced with adversity, we have to remember that it has happened before. Once, there was nothing, then the world came into being. Once, we were slaves, but then we were freed. Wars and persecutions and empires have all come before and, somehow, our people have survived.

We, as individuals, have also survived challenges before. How recent was the Covid pandemic? We can take pride in our own resilience at getting through such troubles before.

Knowing what had gone before, Jonah was able to feel confident that he could face what was to come. Jonah cries out: “You saved my life from the very pits, O Eternal One my God!”

The midrash says that this came when the whale took Jonah down to meet the great sea-monster of the deep, Leviathan. Jonah told that nautical dragon: “You may think you are going to swallow me up, but I carry the promise of Abraham, and I know that one day, when God chooses, it will be you who gets eaten by the righteous.”

Like Jonah, let’s look at the problems ahead of us, and say: “I have faith. I can face you.”

Next, Jonah reflects back on what he has learned. He notices: “Those who cling onto empty folly forsake their own welfare.” He had been willing to stay where he was, clinging onto old vanities, but he did so at the expense of his own soul.

So, he proclaims, instead: “I, with loud thanksgiving, will sacrifice to You, God.”

We, too, can be grateful for what we have, and take on this next year in service of our Creator.

That is the journey on which Jonah took his soul, and it is where I hope to take mine over this Day of Repentance.

I said I wanted to stay still, but stillness is not inactivity. The Rambam understood that serious thinking was the most active you could be. It connects you directly to that Most Active Intellect: the thinking, living God.

In stillness, you can nurture who you are. Jonah was stuck in an underwater pit, but that was when he got most energised. It was when he really engaged in the audit of his soul.

This year, I have spoken to friends and community members and witnessed them say things they normally would never. People who would ordinarily be very liberal, turn racist. People who are normally very peaceful, justifying violence. People who are normally pretty discerning, regurgitating conspiracy theories. People who are usually nuanced, turn to absolutist thinking.

I am not saying this with any judgement. I say it because I’ve done it too.

And when I meet this now, I try to say to myself: I know you are scared and angry, and while you are feeling scared and angry, you can hold all those feelings. You are inside the whale.

But one day, please God, you will be released from this whale, and you will have to reckon with who you became there.

Take care of your soul. It is a precious gift. Don’t let it become too cynical or warped by the horrors that surround it.

That’s my goal for this Yom Kippur: to hold my soul with gentleness, and ask it to be porous and empathic and kind.

I am here, inside the whale. I cannot change what whale I am inside. I cannot stop the waves from crashing or remake the world so it is less scary.

I can only change what I can change. And what I can change, in this moment, on this Yom Kippur, is myself. I just have to deal with who I am here and now.

So, let’s be like Jonah. Let’s accept the whale we’re in, and, yes, despair, but also observe, pray, sing, learn, repent.

And it may be that, when we finally get blown out from that great fish’s blowhole, we might still be better people than when we got swallowed up.

Amen.

The point was not to sacrifice your children

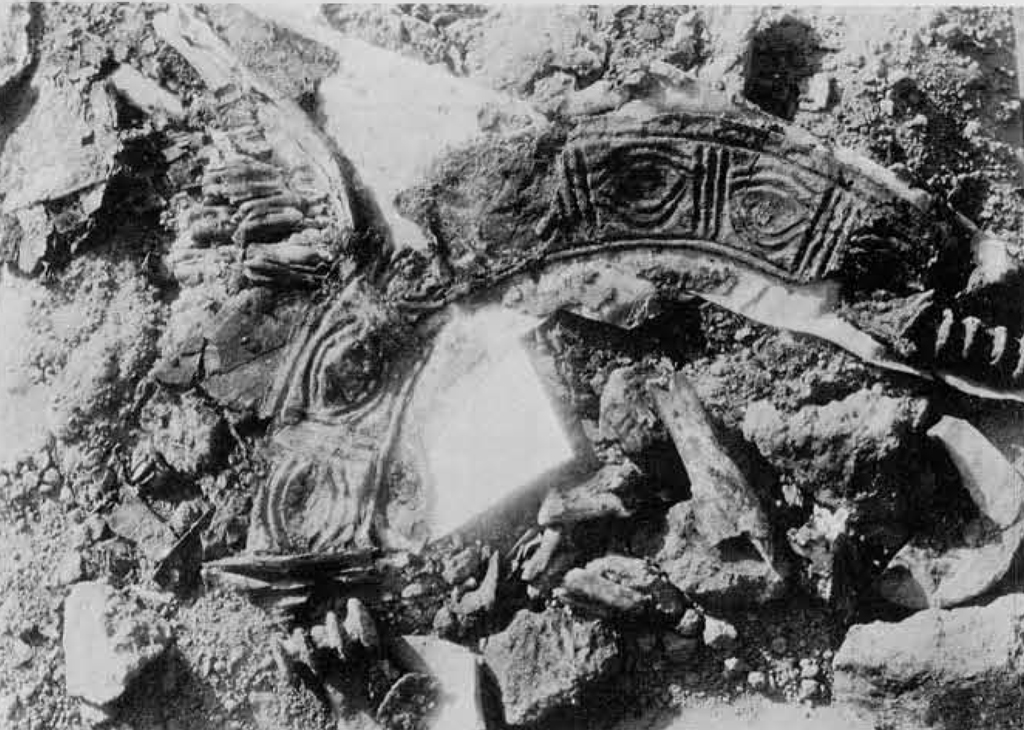

In 1922, archaeologists dug up a site in modern-day southern Iraq. There, they found incredible spans of gold and sophisticated armour, and Iron Age Sumerian artefacts, encased within stone walls. They dubbed this place “the Royal Cemetery of Ur,” an ancient Babylonian mausoleum.

On that site, they also discovered evidence of hundreds of human sacrifices. Among the human sacrifices, a considerable number were children.

Nearly all of the skeletons were killed to accompany an aristocrat or member of the royal family into the afterlife. Some had drunk poison. Some had been bashed over the head with blunt objects. After their death, many were exposed to mercury vapour, so that they would not decompose, but would remain in a lifelike posture, available for public display.

This site dates to sometime around 2,500 BCE in the ancient city of Ur. According to our legends, another figure came from the ancient city of Ur sometime around 2,500 BCE.

His name was Abraham.

In the biblical narrative, Abraham wandered from Ur to ancient Canaan, where he began to worship the One God, and founded Judaism.

The world in which Abraham purportedly lived was rife with child sacrifice. Across the Ancient Near East, archaeologists have uncovered remains of children on slaughtering altars. They have found steles describing when and why they sacrificed children. They have found stories of child sacrifice from the Egyptian, Greek, Sumerian, and Assyrian civilisations.

So problematic was child sacrifice in the ancient world that our Scripture repeatedly condemns it. The book of Leviticus warns: “Do not permit any of your children to be offered as a sacrifice to Molech, for you must not bring shame on the name of your God.” The prophet Jeremiah describes disparagingly how the Pagans “have built the high places to burn their children in the fire as offerings to Baal.” In the Book of Kings, King Josiah tears down the altars where people are sacrificing their children.

Abraham put a stop to the practice of child sacrifice. It seems to happen suddenly, and without warning, and with even less explanation. No reason is given why he abruptly ended all the cultural deference that had gone before and opposed an entrenched religious practice.

The question we now must ask is: why?

One reason that comes to mind is that it is so obviously immoral. Surely it should be self-evident that you don’t kill kids! But that wasn’t obvious to all the people around Abraham. And that wasn’t obvious to traditional commentators, either. In their world, the morally right thing was always to obey God.

A traditional reading says that Abraham stopped child sacrifice in obedience to God. In the story we read today, Abraham is called upon by God to go up on Mount Moriah and slay his son. Only at the summit, when he holds up his arm to murder Isaac, does God stop him, telling Abraham that he has proved his devotion to God by not withholding his son, and that he does not have to kill Isaac.

Yet there are several problems with this story. If we adhere to the traditional reading, God still wanted child sacrifice, and felt that doing so would prove Abraham’s devotion. In fact, nearly all traditionalist readers interpret it this way,saying that obedience before God should be a sacred virtue. A conservative reader of the Bible says that the moral of the story is that we should be subservient to God, and do what we are told.

God said not to perform child sacrifices, so we no longer do. That would mean, then, that if God had said child sacrifice was permitted, we would still be doing it.

In 2007, the Israeli philosopher Omri Boehm offered a radical reinterpretation of the story of the binding of Isaac. The story, Dr Boehm argues, is not about Abraham’s fealty to God, but his disobedience. Dr Boehm shows how, reading against the grain of traditional interpretation, this is not a story where God changes tact and decides not to ask for child sacrifices anymore, but where Abraham rebels against authority and refuses to commit murder.

For Boehm, what was truly radical about the Binding of Isaac was that it set out a new set of values, completely at odds with those of the Ancient Near East. Where other cultures practised child sacrifice because it was part of their established culture, Abraham resisted and put life above law. Where others encouraged obedience to authority, so much that poor people could be killed in the palaces of Ur to serve their masters in the afterlife, Abraham made a virtue of rebellion. For our ancestor Abraham, refusing to follow orders, even God’s, was the true measure of faith. By not killing, even if God seemingly tells you to, you show where your values really lie.

This is not a story about obedience, but rebellion. And that message – of resistance against authority in defence of human life – has much to teach us today.

Boehm reconstructs what the archetypal story of child sacrifice was in the Ancient Near East. Across many cultures and time periods, there was a familiar refrain to how the story went. The community is faced with a crisis: some kind of famine, natural disaster, or war. The community realises that its gods are angry. To placate the gods, the community leader brings his most treasured child and sacrifices him on an altar following the traditional rites. Then, the gods are pleased and the disaster is averted.

We can see that the biblical narrative clearly subverts the storytelling tradition that was around it. In other cultures, the community leader really did sacrifice his special child, and that really did please their Pagan god. In our story, the community leader does not sacrifice his special child, and the national God proclaims no longer to desire human sacrifice. This is already then, a bold message to the rest of the world: you might sacrifice children, but we will not.

Boehm takes this a step further and looks at source criticism for the text. Most scholars of Scripture accept that Torah is the work of human hands over several centuries. One of the ways we try to work out who wrote which bits is by looking at what names for God they use. Whenever we see the name “Elohim” used for God, we tend to think this source is earlier. Whenever we see the name “YHVH” used for God, we tend to assume the source is a later edit by Temple priests.

The story of the binding of Isaac is odd because it uses the name “Elohim” almost the entire way through, until the very end, when the angel of God appears and tells Abraham not to kill Isaac. That means that most of the text is from the early tradition and only the very end part, where the angel of God tells Abraham not to kill Isaac, comes from the later priests.

So, Boehm asks, what was the earlier version of the text? If you take out the verses where God is YHVH and have only the version where God is Elohim, what story remains?

Well, in the version that we know, where both stories are combined, an angel of God calls out and tells Abraham not to sacrifice Isaac. That’s the bit where God is YHVH. If you take that out, and have only God as Elohim, Abraham makes the decision himself. No angel comes to tell him what to do. Next, if we cut out the parts where God is YHVH, there is no praise from the angel, telling Abraham he made the right choice. Instead, you get a story where Abraham deliberately disobeys his God because he loves the life of his son more.

The earliest version of the text, before the Torah was edited and a later gloss was added, is one in which Abraham is commanded by God to sacrifice Isaac, goes all the way up Mount Moriah, and then refuses. Without prompt or praise from God, Abraham decides to sacrifice a ram instead of his son. In the earliest version of the biblical narrative, when source critics have stripped away priestly edits, God tells Abraham to sacrifice his son and Abraham rebels.

The earliest version, then, is an even more radical counter-narrative to the other stories of the Ancient Near East. Not only do we not sacrifice children. We also recognise that sometimes you have to say no to your god. In this version, rebellion is more important than obedience, especially when it comes to human life.

This isn’t just a modern Bible scholar being provocative and trying to sell books. In fact, Boehm shows, this was also the view of respected Torah scholars like Maimonides and ibn Caspi. These great mediaeval thinkers didn’t think of the Torah as having multiple authors, but they could see that multiple stories were going on in one narrative. One, they thought, was the simple tale of obedience, intended for the masses. But hiding between the lines was another one, for the truly enlightened, that tells the story of Abraham’s refusal.

Boehm terms this “a religious model of disobedience.” By the end of the book, you go away with the unshakable impression that Boehm is right. True faith, he says, is not always doing what you think God is telling you. Sometimes it is reaching deep within your own soul to find moral truth. Sometimes you really show your values by how you defy orders.

In his conclusion, Boehm takes aim at Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, an American religious leader, who lives in the West Bank settlement of Efrat. Rabbi Riskin had said, in his analysis of the binding of Isaac, that Abraham was a model of faith by his willingness to kill his son. Riskin insisted that he was willing to sacrifice his own children in service of the state of Israel.

This, says Boehm, is precisely the opposite of the message of the binding of Isaac. The point was not to let your children die. The point was to bring a final end to child sacrifice. The point was not to submit to unjust authority, but to rebel in defence of life.

Rabbi Riskin does not realise it, but by offering child sacrifice, he is really advocating for the Pagan god. He is describing the explicitly forbidden ritual of allowing your children to die.

Abraham thoroughly opposed these false gods who demanded ritual murder. They were idols; and child sacrifice a monstrous practice that we were supposed to banish to the past. The very essence and origin of Jewish monotheism is its thorough rejection of killing children.

Boehm could not have known how pertinent his words would become. This year has been one of the worst that those of us connected to Israel can remember. Beginning on October 7th, with Hamas’s horrendous massacres and kidnappings, the last Jewish year has seen us rapt in a horrific and seemingly never-ending war.

This year, thousands of Israelis were killed. This is the first time in a generation that more Israeli youth have died in war than in car crashes. Reading through the list of names, it is remarkable how many of the soldiers were teenagers.

That is not to even mention the 40,000 Palestinians whom the IDF have killed. According to Netanyahu’s own statements, well over half were civilians. Around a third were children. As famine and food insecurity rises, the risk of deaths will only accelerate. It has been agonising to witness, and I cannot imagine how painful it has been to live through.

Yet, during my month in Jerusalem, I saw that the voice of Abraham has not been extinguished. There are few groups I hold in higher esteem than the Israeli peace movement. Against untold threats and coercion, in a society that can be intensely hostile to their message, they uphold Abraham’s injunction against killing.

One of the leaders of the cause against war was Rachel Goldberg-Polin. On October 7th, her 19-year-old son, Hersh, was kidnapped by Hamas. His arm was blown off and he was taken hostage in Gaza. From the very outset, Mrs. Golderg-Polin argued fervently for a ceasefire and a hostage deal that would bring her son home. She warned that the only way her son would come home alive would be as part of political negotiations.

At the end of August, as Israeli forces neared to capture Hersh as part of a military operation, Hamas shot her son, Hersh, in the head.

Rachel Goldberg-Polin’s refusal to give up hope, refusal to sacrifice her son, and steadfast insistence on peaceful alternatives is a true model of Abraham’s faith.

And it involves serious rebellion too. When I met with hostage families in Jerusalem, I was shocked to hear how, for protesting against the war to bring their families home, they had been beaten up by Ben Gvir’s police. I saw this with my own eyes when I marched alongside them. People shouted and jeered at them, and the police came at them with truncheons.

In July, when I went with Rabbis for Human Rights to defend a village in the West Bank against settler violence, we were joined in our car full of nerdy Talmud scholars by a surprising first-timer. A strapping 18-year-old got in to volunteer in supporting the Palestinian village. What was most remarkable was that he himself lived in a West Bank settlement.

He explained that he had refused to serve in the military. He did not know that others had done it before, or that there were organisations to support Israeli military refusers. Instead, he said, he thought to himself: “if I don’t go, they won’t kill me; if I do go, I might kill someone.” What could be a truer expression of Abraham’s message: no to death! No to death, no matter the cost.

He really had to rebel. For refusing to serve in the war, the conscientious objector I met spent seven months in jail. Still now, there are dozens of Israeli teenagers in prison because they would not support the war.

Throughout my time in Jerusalem, I attended every protest against the war and for hostage release that I could. One of the most profound groups I witnessed was the Women in White, a feminist anti-war group going back decades. One of these women, with grey hair and the look of a veteran campaigner, held a placard that read in Hebrew: “we do not have spare children for pointless wars.”

Is this not exactly what Abraham would say? We will not sacrifice our children on the altar of war!

Theirs is truly the voice of Abraham, the true voice of Judaism. It is the voice that opposes child sacrifice. Theirs is the voice that upholds the God who chooses life.

Talmud tells us that, when we blast the shofar one hundred times on Rosh Hashanah, we are repeating the one hundred wails of Sisera’s mother when she heard her son had died. Sisera was, in fact, an enemy of the Israelites, who waged war on Deborah’s armies, and was killed by the Jewish heroine, Yael. Still, at this holy time of year, we place the grief of Sisera’s mother at the forefront of our prayers.

We take the cry of every mother who has lost a child and we make it our cry.

Thousands of years after the Sumerian Empire had ceased existing, archaeologists dug up its remains, and saw a society that practised child sacrifice. From the very fact of how they carried out murder and permitted death, the excavators could tell a great deal about what kind of society this was. One that killed people to serve their wealthy and their gods.

One day, thousands of years from now, historians may look upon us too, and ask questions about what our society was like, and what we valued. May we take upon ourselves the mantle of Abraham.

May they look back and say that we chose to value life. May they look back and see that our people despised death and war. May they look back on us and see a society that practised faithful disobedience.

Amen.

Why Jews do not believe in Hell

When I was a teenager, I went on some kind of away day with other Progressive Jewish youth.

The rabbi – I can’t remember who – told a story.

A woman dies and enters the afterlife. There, the angels greet her and offer her a tour of the two possible residencies: Heaven and Hell.

First, she enters Hell. It is just one long table, filled with delicious foods. The only problem is that they all have splinted arms. Their limbs are fixed in such positions that they could not possibly feed themselves. They struggle, thrusting their hands against the table and the bowl. Even if they successfully get some food, they cannot retract their arms back to their mouths. They are eternally starving, crying out in anguish. That was Hell.

Next, she enters Heaven. Well, it’s exactly the same place! There is a long table, filled with delicious foods, and all the people sitting at it have splinted arms. But here, there is banqueting and merriment; everyone is eating and singing and chatting. The difference is simply that, while in Hell, people only tried to feed themselves, here in Heaven they feed each other.

She ran back to Hell to share this solution with the poor souls trapped there. She whispered in the ear of one starving man, “You do not have to go hungry. Use your spoon to feed your neighbor, and he will surely return the favour and feed you.”

“‘You expect me to feed the detestable man sitting across the table?’ said the man angrily. ‘I would rather starve than give him the pleasure of eating!’

The difference between Heaven and Hell isn’t the setting, but how people treat each other.

At the conclusion of this story, one of the other teenagers – I can’t remember who, but I promise it wasn’t me – put his hand up and said: “But I thought Jews don’t believe in Hell?”

The rabbi shrugged and said: “True. It’s just a story.”

Years later, though, the story, and the resultant question, have stuck with me.

Was it just a story? Do Jews really have no concept of Hell?

The truth is complicated.

Among most Jews, you will find very little assent to the idea of punishment in the afterlife.

In part, that is simply because most of Judaism does not have a clear systematic theology. There is no Jewish version of the catechism, affirming a set of views about the nature of God, the point of this life, and the outcomes in the next.

Rather, Judaism holds multiple and conflicting ideas. On almost every issue, you can find rabbinic voices in tension, holding opposite views that are part of the Truth of a greater whole. We don’t mandate ideas, we entertain them.

So, a better question would be: does Judaism entertain the idea of Hell?

And the answer is still: it’s complicated.

Yes, it does. The story that rabbi told of the people with the splinted arms comes from the Lithuanian-Jewish musar tradition. It is attributed to Rabbi Haim of Romshishok.

The idea of pious Jews going on tours of Heaven and Hell has a long history. In the Palestinian Talmud, a pious Jew sees, to his horror, his devoted and charitable friend die but go unmourned. On the same day, a tax collector, a collaborator with the Roman Empire, dies and the entire city stops to attend his funeral.

To comfort the pious man, God grants him a dream-vision of what happened to each of them in the afterlife. His righteous friend enjoys a life of happiness and plenty in Heaven, surrounded by gardens and orchards. The tax collector, on the other hand, sits by waters, desperately thirsty, with his tongue stretched out, but unable to drink. Where one gave in this life, he received in the next. Where the other took in this life, he was famished in the next.

This is a revenge fantasy. The story comes from oppressed people coming to terms with the success of their conquerors and the humiliation of the good in their generation.

The fantasy is powerful, and the motifs repeat throughout Jewish history. In almost every generation, you can find people pondering about how bad people will be punished and good people will be rewarded when this life is over.

But, with equal frequency, you can find Jewish scepticism about this view of the world. The Babylonian rabbis warn us not to speculate on what lies in the hereafter, for God alone knows such secrets. Our greatest philosophers like Rambam and Gersonides strenuously deny any concept of post-mortem torture.

These debates have persisted even into the modern era. During the Enlightenment, there were those who claimed that a rational religion could have no place for the primitive nonsense of Hell. Equally, there were those who said belief in divine retribution was the hallmark of a civilised belief system.

So where did the idea come from, asserted so confidently by that teenager on a day trip, that Jews have no concept of Hell?

The truth is it is very recent.

In surveys of attitudes, Jewish belief in Hell plummeted after the Second World War.

In all the revenge fantasies and horror stories that people could concoct about Hell, not one of them sounded as bad as Auschwitz.

There is no conceivable God who is cruel enough to do what the Nazis did. No such God would be worthy of worship.

We have no need to fantasise about freezing cold places filled with trapped souls, or raging furnaces. We need not imagine a world after this one where people are starved and tortured and brutalised. We know that world has already existed here on earth.

Isn’t Hell already here still? Doesn’t it still exist right here in this world for all those mothers putting their toddlers in dinghies hoping the sea will take them away from the war? Don’t those horrors already exist in for people working in Congolese gold mines or Bangladeshi sweat shops?

Hell is already here. It is war and occupation and famine and drought and slavery and trafficking. There is no need for nightmares of brimstone when people are living these things every day.

That was the point of the story that rabbi was telling us.

The difference between Heaven and Hell isn’t the setting, but how people treat each other.

We already live in a world of plenty. We have the flowing streams and gardens and orchards our sages imagine. But, like the inhabitants of Hell, we are pumping sewage into the streams, turning the gardens into car parks, and logging the orchards for things we do not need.

We are sat before a fine banquet where there is enough for everyone, but half the population are not eating while a tiny minority are engorged with more than they need. We are living the vision laid out in the parable.

Yes, this world is a Hell, but it could be a Heaven too.

The difference between Heaven and Hell isn’t the setting, but how people treat each other.

Look at all that we have. Look at the support we can give each other. We may have splinted arms but all we need do is outstretch them.

We have the capacity to annihilate all hunger, poverty, and war. We really could end all prejudice and oppression. This planet could be a paradise!

And, if we know that we can make this world a Heaven, why would we wait until we die?

Shabbat shalom.

Creating cultures of repentance

We are, apparently, in the grips of a culture war.

It must be an especially intense one, because the newspapers seem to report on it more than the wars in Syria, the Central African Republic, or Yemen, combined.

According to the Telegraph, this war is our generation’s great fight. It was even the foremost topic in the leadership battle for who would be our next Prime Minister, far above the economy, climate change, or Coronavirus recovery.

Just this last month, its belligerents have included Disney, Buckingham Palace, the British Medical Journal, cyclists in Surrey, alien library mascots, and rural museums.

But which side should I choose? One side is called “the woke mob.” That seems like it should be my team. After all, they are the successor organisation to the Political Correctness Brigade, of which I was a card-carrying member when that was all the rage.

The so-called “woke mob” are drawing attention to many historic and present injustices. From acknowledging that much of Britain was built on the back of the slave trade to criticising comedians who say that Hitler did a good thing by murdering Gypsies, they are shining a light on wrongs in society.

The trouble is, I hate to be on the losing side. For all the noise and bluster, this campaign hasn’t managed to get anyone who deserves it. The most virulent racists, misogynists, abusers, and profiteers remain largely unabated.

Even if they were successful, I find the underlying ideas troubling. It seems to assume that people’s wrong actions put them outside of rehabilitation into decent society. Some people are just too bad.

This strikes as puritanical. While the claims that so-called “cancel culture” is ruining civilisation are wildly overstated, it is right to be concerned by a philosophy that excludes and punishes.

So, will I throw my lot in with the conservatives? Perhaps it’s time I joined this fightback against the woke mob.

On this side, proponents say that they are combatting cancel culture. How are they doing this? By deliberately upsetting people. They actively endeavour to elicit a reaction by saying the most hurtful thing they can.

When, inevitably, these public figures receive the condemnation they deserve, they go on tour to lament how sensitive and censorious their opponents are. As a result, they get book deals, newspaper columns, and increased ticket sales.

Ultimately, this reaction to “cancel culture” is a mirror of what it opposes. It agrees that people cannot heal or do wrong. It celebrates the idea that people are bad, and provides a foil that allows people to prop up their worst selves.

If this is the culture war, I want no part in it. Neither side is interested in the hard work of repentance, apologies, and forgiveness. It offers only two possible cultures: one in which nobody can do right and one in which nobody can do wrong.

This is the antithesis of the Jewish approach to harm.

Our religion has never tried to divide up the world into good and bad people. We have no interest in flaunting our cruelty, nor in banishing people.

Instead, the Jewish approach is to accept that we are all broken people in a broken world. We are all doing wrong. We all hurt others, and have been hurt ourselves. The Jewish approach is to listen to the yetzer hatov within us: that force of conscience, willing us to do better.

The culture we want to create is one of teshuvah: one in which people acknowledge they have done wrong, seek to make amends, apologise, and earn forgiveness.

A few weeks ago, just in time for Yom Kippur, Rabbi Danya Rutenberg released a new book, called Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World.

Rabbi Rutenberg argues that Jewish approaches to repentance and repair can help resolve the troubled society we live in.

She locates some of the issues in America’s lack of repentance culture in its history. After the Civil War, preachers and pundits encouraged the people of the now United States of America to forgive, forget and move on. It doesn’t matter now, they said, who owned slaves or campaigned for racism, now they were all Americans.

The Civil War veterans established a social basis in which there was no need for repentance or reparations, but that forgiveness had to be offered unconditionally. Without investing the work in true teshuvah, they created an unapologetic society that refused to acknowledge harm.

We, in Britain, also have an unapologetic and unforgiving culture, but our history is different.

True, we also failed to properly address our history of slavery. When the slave trade was abolished at the start of the 19th Century, former slave traders and slave owners were given substantial compensation. The former slaves themselves were not offered so much as an apology.

But we have not been through a conscious process of nation-building the way the United States has.

In fact, Britain has not really gone through any process of cultural rebuild since the collapse of its Empire. In 1960, the then Prime Minister Harold Macmillan gave his famous speech, in which he acknowledged “the wind of change” driving decolonisation. Whether Brits liked it or not, he said, the national liberation of former colonies was a political fact.

At that time, he warned “what is now on trial is much more than our military strength or our diplomatic and administrative skill. It is our way of life.” Britain would need to work out who it was and what its values were before it could move forward and expect the family of nations to work with it.

More than 60 years later, it seems we still have not done that. As a nation, we are simply not clear on who we are. We do not know what makes us good, where we have gone wrong, or what we could do to be better.

So, we are caught in shame and denial. Shame that, if we admitted to having caused harm, we would have to accept being irredeemably evil. Denial that we could be bad, and so could ever have done wrong.

The two sides of the so-called “cancel culture” debate represent those two responses to our uncertainty. Those who are so ashamed of Britain’s history of racism and sexism that they have no idea how to move forward. And those who are so in denial of history that they refuse to accept it ever happened, or that it really represented the great moral injury that its victims perceived.

This creates a toxic national culture, stultified by its past and incapable of looking toward its future.

So, Rabbi Rutenberg suggests, we need to build an alternative culture, one built on teshuvah. We need a culture where people feel guilty about what they have done wrong and try to repair it. For those who have been hurt, that means centering their needs as victims. For those who have done wrong, that means offering them the love and support to become better people.

Rutenberg draws on the teachings of the Rambam to suggest how that might happen. The Rambam outlined five steps people could take towards atonement, in his major law code, Mishneh Torah.

First, you must admit to having done wrong. Ideally, you should stand up publicly, with witnesses, and declare your errors.

Next, you must try to become a better person.

Then, you must make amends, however possible.

Then, and only then, can you make an apology.

Finally, you will be faced with a similar opportunity to do wrong again. If you have taken the preceding steps seriously, you will not repeat your past mistakes.

For me, the crucial thing about Ruttenberg’s reframing of Rambam, is that it puts apologies nearly last. It centres the more difficult part: becoming the kind of person that does not repeat offences. It asks us to cultivate virtue, looking for what is best in us and trying to improve it.

You must investigate why you did what you did, and understand better the harm you caused. You must read and reflect and listen so that you can empathise with the wronged party. And, through this process, you must cultivate the personality of one who does not hurt again.

That is what Yom Kippur is really about. It is not about beating ourselves up for things we cannot change, nor about stubbornly holding onto our worst habits. It is not about shrugging off past injustices, nor is it about asking others to forget our faults.

It’s about the real effort needed to look at who we are, examine ourselves, and become a better version of that.

If there is a culture war going on, that is the culture I want to see.

I want us to live in a society where people think about their actions and seek to do good. I want us to see a world where nobody is excluded – not because they are wrong or because they have been wronged. One where we are all included, together, in improving ourselves and our cultural life.

To build such a system, we need to start small. We cannot change Britain overnight.

We have to begin with the smallest pieces first. Tonight, we begin doing that work on ourselves.

Gmar chatimah tovah – may you be sealed for good.

Why do people get sick?

Why do people get sick?

In a year when so many have experienced ill health, it is worth asking why this has happened. Throughout the pandemic, we have been reminded that some will get the virus with no symptoms; some will get the virus and recover; some will get the virus and will not recover. But what determines who gets sick and who gets better? Who decides who has to suffer and who will not?

There are plenty of medical professionals in this congregation who can answer part of that question much better than I can. Statistics, underlying factors, mitigating circumstances, health inequalities, access to medicine. All of these things certainly play a role.

But they don’t answer the fundamental question that animates us: why? Why my loved one? Why me? That is not a medical question but an existential one. It is about whether there is a God, whether that God cares, and what a religious Jew might do to change their outcomes.

For that, we look to the Jewish tradition. Let’s start with this week’s parashah. Here, we read one of the earliest examples of a supplicatory prayer. Moses sees his sister, Miriam, covered in scaly skin disease. He cries out: “El na rafa na la.” God, please, heal her, please. We hear the desperation in Moses’ voice as he twice begs: “please.” Don’t let her become like one of the walking dead.

In this story, there is a clear explanation for why Miriam gets sick and why she gets better. Miriam’s skin disease is a punishment. She insulted Moses’ wife, talking about her behind her back with Aaron.

When she gets healed, it is because she atones for her sins and Moses forgives her. She goes to great lengths of prayer and ritual to have her body restored. Sickness is a punishment and health is a reward.

In some frum communities, you might still hear this explanation. All kinds of maladies are offered as warnings for gossiping. When people get sick, they’re encouraged to check their mezuzot to make sure their protective amulets are in good working order.

In some ways, these are harmless superstitions. When everything feels out of control, why not look for reasons and things you can do? But hanging your beliefs on this is dangerous. Plenty of righteous people get sick and plenty of wicked people lead long and healthy lives.

If you follow the logic of this Torah story, you run the risk that, when your loved one’s health deteriorates, you might blame them for their ethical conduct, when really there is nothing they could do. It is a cruel theology that blames the victim for their sickness.

In the Talmud, the rabbis felt a similar discomfort. They decided that skin diseases were an altar for atonement. When people got sick, it was God’s way of testing the most beloved. The righteous would suffer greatly in this world so that they would suffer far less in the next.

When Rabbi Yohanan fell ill, Rabbi Hanina went to visit him at his sick bed. He asked him: “Do you want to reap the benefits of this suffering?” Rabbi Yohanan said he did not want the rewards for being sick, and was immediately healed.

We hear these ideas today, too. People will say that God sends the toughest challenges to the strongest soldiers. But I don’t think this theology is any more tenable. How can anyone say to a child with cancer that their sickness is an act of God’s love? Who could justify such a belief?

No. The truth is that these theories of reward and punishment should leave us cold. We live in a world full of sickness and suffering, and it’s attribution is entirely random.

Maimonides, a 13th Century philosopher, saw that these explanations for sickness did not work. He was a doctor; the chief physician to the Sultan in Egypt. He had read every medical textbook and saw long queues of people with various ailments every day. How could he, with all his knowledge, think that sickness was a punishment or a reward?

Maimonides taught that God has providence over life in general but not over each life in particular. God has a plan for the world, but is not going to intervene in individual cases of recovery. He disparaged the idea that mezuzot were amulets or that people could impact their health outcomes with prayer.

I feel compelled to agree with Maimonides’ rationalist Judaism. Sickness is random and inexplicable. So is health. The statistics and medical knowledge that I set aside at the start of this sermon have much better answers than I can muster.

So, what do we do? We, who are not healthcare professionals or clinicians seeking a cure?

Like Moses, seeing the sickness of Miriam, we pray. We pray with our loved ones, not because we think it will make God any more favourable to them, but because it is a source of comfort to those who are sick. Praying with someone shows that you love them and care about their recovery. We do it for the sake of our loving relationships.

Like Rabbi Hanina, seeing the sickness of Rabbi Yohanan, we visit the sick. We attend to people, not because we imagine we can magically cure them with words, but because company is the greatest source of strength in trying times. We go to see people in hospital, not for their bodies, but for their souls.

And, like Maimonides, we approach the world with humility. We refuse to believe in superstitions that are false or harmful. We accept that we live in a mystery and there is much we do not know.

In this time of sickness and difficulty, it is very Jewish to ask: “why do people get sick?” The Jewish response to questions is to ask more questions. And the most Jewish question we can ask here is: “when people are sick, how can I help?”

Shabbat shalom.

I gave this sermon at Newcastle Reform Synagogue for Parashat Behaalotchah on 29th May 2021.

Go for yourself

Trying to get by with biblical Hebrew with modern Hebrew speakers is difficult. Among a group in Jerusalem this summer, I tried to coax out a dog, saying “Lech lecha, celev.” The Israelis around me burst out laughing. “What? What did I say?” I asked. “Nothing,” they said. “It doesn’t mean anything.”

I had just repeated the first words of our parashah, when God instructs Abraham to get out of Haran and go to Canaan. Without context, the expression was bizarre. Phrases that were once meaningful in this language can lose their sense. But, for our commentators throughout history, this specific phrase has been perplexing. Without the vowels we might think it is emphatic – a repetition of the same verb, telling Abraham “go, go, get out.” But the Masoretic markings are quite clear. This is not “lech lech” but “lech lecha” – which could be read ‘go to yourself’, or ‘go for yourself’, or ‘go as yourself’… It is a strange construction.

Ramban suggests that it’s just an idiom of biblical Hebrew. He points to other examples in Jeremiah and Deuteronomy where similar constructions are used. But that answer feels disappointing. Why this idiom? And why here? Every idiom has a purpose, even if that purpose isn’t even entirely clear to the native speaker.

The answer I like best comes from Rashi. Rashi says “go for your own benefit, for your own advantage”. This puts the rest of the sentence into context: “and all the families of the earth shall be blessed through you.” Don’t go for their sake. Go for your own sake. But when you go for your own sake, when you go knowing that you are seeking out a blessing for yourself, then everyone will receive that blessing too.

It calls to mind the distinction between charity and solidarity. That idea was summarised by Lilla Watson, an Australian indigenous rights activist, in her address to the UN Women’s Conference in Nairobi in 1985: “If you have come here to help me you are wasting your time, but if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” Watson herself has challenged the attribution, saying that it was thinking that had come out of collective work by indigenous women in Queensland over a long period of time.

Indeed, differentiating between charity and solidarity has long been a feature of thought for oppressed peoples. Charity, seeking to help people for their own sake without any regard for your own, is surely a noble feeling. But it leaves the person who gives it feeling better than the one who receives it. For the one who gives it, it leaves them feeling helpful, assuages their conscience, and contributes to a sense that they are doing the right thing. For the recipient, it can leave them feeling powerless, pitied, supported, and not treated as a full human being.

Charity is ultimately, too, not that helpful to the one giving it. It turns human interaction into a form of sacrifice, based on guilt, self-effacement and pity. It forces people to ignore their own lived realities and struggles, and put themselves at a position of distance from others.

While charity can address material needs in a positive way, it reminds everyone of the power relations that caused the need for charity in the first place. It reminds the donor of their power and the receiver of their lack. It can even reinforce those structures, as the impoverished turn to the donors as a source of wealth rather than looking to their own talents. The donor can impose restrictions on how the money is used or on how the receiver might conduct themselves in ways that ultimately secure the authority of the donor.

Solidarity asks us to “lech lecha” – to go for ourselves, to go as ourselves. It asks us to come to problems as full people with our own issues and concerns that we need to address. It asks us to treat everybody as if they, too, are going for themselves: full human beings who have a great deal in common with us and their own unique purposes.

Solidarity requires both parties to feel vulnerable together. It asks that the person motivated to give charity considers their own interests and what stake they have in changing the current circumstances. It also asks both parties to work together: they have a common interest and need to empower each other. Solidarity places people’s self-respect and cooperation at the centre of organising change.

Rambam picks up this theme in his eight levels of ‘tzedaka’. The word ‘tzedaka’ is often translated as ‘charity’, but it shares a common root with the word for ‘justice’. The concepts of charity and solidarity are held together by this same word, so Rambam needed to spell out the differences between different forms of giving. Like the indigenous activists of Australia, Rambam puts solidarity on a much higher level than charity. He considers “empowering others with meaningful employment” to be the highest level of tzedaka. Unlike giving into the hands of the poor, empowerment such as this ensures that everyone’s dignity is preserved, and everyone benefits from the work.

So it is that G-d says to Abraham: “Go for your own sake and all the families of the earth will be blessed through you.” When you go out considering your own self-respect first and foremost, it follows that everyone else can act from theirs. Abraham does not go out to save the world. He goes out to save himself. But by being prepared to take risks for his own soul, he sets an example and sets the wheels in motion that everybody can seek out G-d’s blessing.

That is how the nations became blessed through Abraham. As we approach the challenges of our day, we should seek to ask the same questions as he was forced to. What do I really need? What does G-d require of me? How can I see others as full human beings and respond to their needs? How can I go for myself, so as to be a blessing for others?

Go for yourself, and all the nations of the world will be blessed through you.

I gave this sermon on the morning of Thursday 18th October at Leo Baeck College for Parashat Lech Lecha.