At present, Reform and Liberal Judaism are deciding whether to become a single movement. You will be able to vote on this, and I encourage you to do so.

As the procedural questions unfold, it is hard to imagine how strongly felt the ideological divisions were between the two movements, even forty years ago. I believe, however, that those differences are now almost entirely within the movements, rather than between them.

On some fronts, we will find unity, and on others, differences will remain.

There is one point, however, which, to me, is so intrinsic to Liberal thought that I could not stand it to see it lost. That is: there is no such thing as a Jewish race.

There is no such thing as Jewish blood, as a Jewish womb, as Jewish DNA, or as Jewish features.

It is precisely because our Liberal tradition teaches that there is no Jewish race that we have been able to fully embrace converts and, from the very beginning, accepted patrilineal Jews.

These ideas were critical stumbling-blocks to merger attempts in previous decades. Reform Judaism would not accept patrilineal Jews, and insisted that converts went and were reborn from the “Jewish womb” of a mikvah.

In the past few years, Reform Judaism has come to accept patrilineal Jews, and Liberal Judaism has come to accept that the mikvah can be a meaningful ritual.

Yet not everyone has come to accept the underlying ideology that made these matters so central to Liberal Judaism. The originators of our movement saw Judaism as a religious community, where Jewishness was communicated socially, not “biologically.”

That is no longer a sectarian issue. There are Reform rabbis who ardently agree on this point; and there are Liberals who, instead of denying any racial Jewishness, focus on being “inclusive” about who belongs.

Rejecting the idea of a Jewish race was absolutely foundational to early Liberal thinkers. Regardless of whatever new ideas emerge as rabbis come together, I intend to hold doggedly to their understanding of Jewishness.

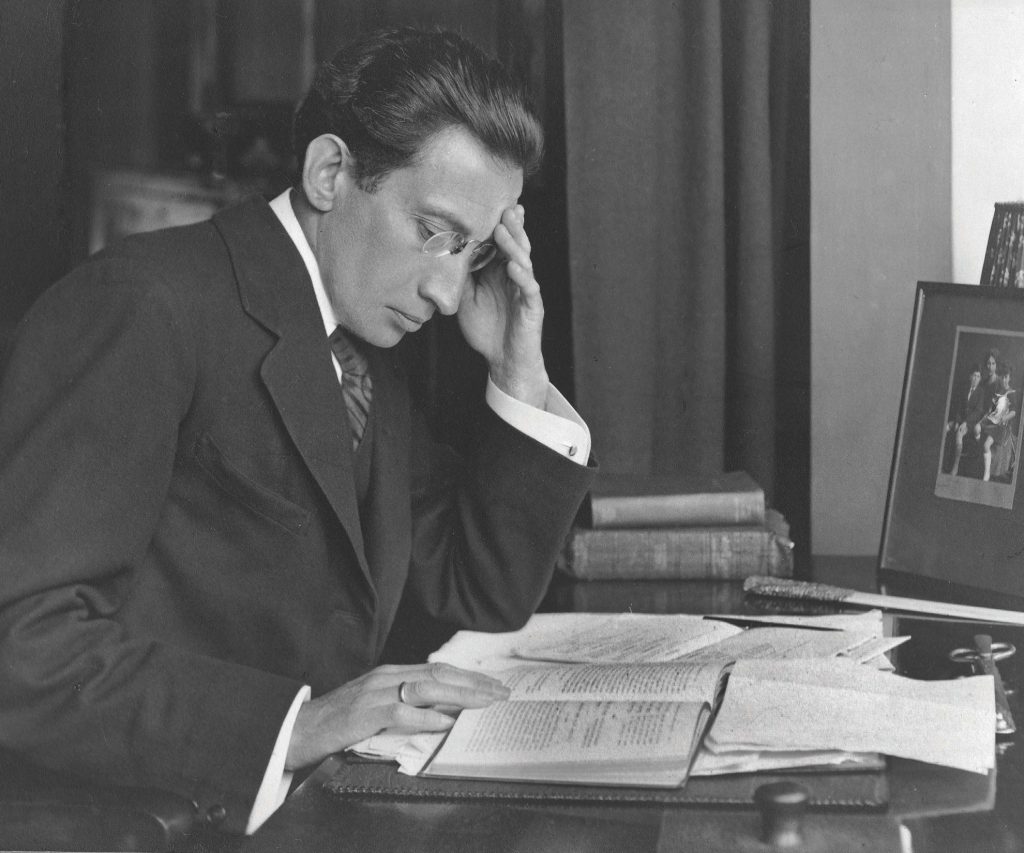

Israel Mattuck was the first Liberal rabbi in the UK. In 1911, he was recruited by Lily Montagu and Claude Montefiore from America to lead the Liberal Jewish Synagogue in St John’s Wood. He was a prolific preacher, ideologue, and scholar.

At the LJS, Dr Mattuck taught a Confirmation class, for 16-year-olds affirming their faith. He later took his notes and turned them into a book, entitled Essentials of Liberal Judaism so that everyone would know what he thought it meant to be a Jew.

Jews, he insisted, were not a race, but spanned the globe. What made people Jewish was that they held Jewish ideas, followed a Jewish way of life, and kept Jewish observances.

He wrote: “In spite of all the differences among them, the Jews of the world constitute a people; but they are a people in a different sense from any other people. Their unity is based on religion and history.”

Editing in 1947, Mattuck was eager to avoid any misconceptions. He insisted that this history was not an unbroken tale of misery and persecution, but one of great spiritual achievements. We were, he said, the first witnesses to God’s unity through the revelation at Sinai. Our history was that of the prophets, the priests, the scholars, the mystics, and all those who sought to reach closer to religious truth.

Mattuck was clear that you could not be Jewish in anything more than name if you rested on race. You want to be a Jew? Walk humbly with God, taught Rabbi Mattuck from the prophet Micah.

There is no race – only a demand to live right.

Now, you may be thinking, this all sounds a lot like the Critical Race Theory that Mr Trump so zealously warned us about. Indeed it is! And the American President has good reason to fear people taking a critical approach to race.

In the USA, races were invented to divide and rule people so that the wealthy whites could maintain their plantation economy. Poor whites were incentivised to enforce and uphold slavery by being given some privileges on the basis of their skin colour.

As a result, they felt they could identify with the rich whites, even though they had very little in common with them socially or economically. Using racism, they demeaned and humiliated the stolen Africans so that they would not have the confidence to challenge their own condition.

That is why race-critical scholars in America have the slogan: “race exists because of racism, not the other way round.”

In Race: A Theological Account, the African-American scholar of religion J. Kameron Carter shows how racist ideology had earlier roots – in how European Christians treated Jews.

To create a system where Jews were second-class citizens, they needed an ideology where Jews were defective human beings. So they made up stories about Jewish bodies, Jewish blood, Jewish noses and hair – even Jewish horns – to justify their system of oppression. It was a nasty division for the purposes of exploitation.

This was exactly why Mattuck was so resistant to talk of Jews as a race, and so adamant about our religion.

In 1939, Mattuck wrote his first major work, What are the Jews?, which was a harsh rebuttal, not only to Jewish racial nationalism, but to racial nationalism as such.

We belong everywhere, he asserted. In the Age of Enlightenment, all citizenship should be communicated on civic grounds, never on ethnic or religious ones.

A Jew, he felt, could be a nationalist, but they must first adhere to the religious calling. That is: they could be Jewish and happen to have nationalist leanings, but it could not define them as Jewish.

Nevertheless, he thought that, by properly conceiving of ourselves as a religion, we would be more likely drawn to universal ethics. We would measure our Jewishness by our conduct towards others and our connection with our God, rather than by the supposed quality of our genetic make-up. We could pull apart the stories that separated people and build common bonds.

Racial thinking, thought Mattuck, must be resisted.

Race is a horrible and divisive lie. Religion is a beautiful and unifying truth.

I want to be open about why this idea is hard for others to hold.

It is more demanding. It says that nobody can take their Jewishness for granted, and must work for it. It means that you cannot be “born” Jewish, but have to live Jewish. It sets high ethical and practical demands on anyone who claims Jewishness.

When we say that there is no Jewish race, we also mean that somebody with an unbroken chain of matrilineal descent but without any Jewish upbringing or identity must also learn how to be Jewish, in the same way as a patrilineal Jew would. Everyone has to properly engage with the traditions and practices. Contrary to the doctrine of inclusion, this makes us more exclusive than the Orthodox.

Denying the existence of a Jewish race also has profound implications for how we engage with Israel. If we are a religious community, the demand to achieve a Jewish ethnic majority – still less racial supremacy – is not just grotesque. It is absurd. The measure of whether the state was sufficiently Jewish would not be by how many Jews there were, but by how well it upheld Jewish moral values.

Yet it is precisely because of this more demanding approach to Jewishness that I will keep holding onto it. The call that we be moral in our dealings, conscientious in our practices, and connected with our traditions is a far better one than the narrow pull of racial nationalism.

Through such a religion, we may connect to every other Jew in a spirit of solidarity.

Through religion, we may connect to all of humanity, by recognising our shared Creator.

Through religion, we may draw nearer to the mystery that is our God.

Through religion, we may live out the words of our haftarah: “For you who revere My Name, the sunbeams of righteousness will rise, with healing in their wings. Then you will go forth and skip about like calves from the stall.”

Shabbat shalom.