There are ways of remembering intended to make you forget.

There are ways of forgetting intended to help you remember.

So, says the Torah, remember in order not to forget.

This week is Shabbat Zachor, the Sabbath of remembrance. Just before Purim, we are called to read three additional lines of Scripture. Deuteronomy instructs:

Remember what Amalek did to you on your journey out of Egypt [… ] You shall erase the memory of Amalek from under heaven. Do not forget.

Remember… erase the memory… do not forget.

Is the demand to remember not contradicted by the insistence on erasing the memory?

Is the commandment to remember not exactly the same as the one not to forget?

Perhaps not. There are ways of remembering that encourage forgetting, and ways of forgetting that make you remember.

Alan Bennett’s play, The History Boys, is an exploration of what it means to teach history, and what we can learn from it.

In a powerful scene, the newest teacher, Tom Irwin, takes his sixth-form grammar school students on a tour of a war cemetery.

As they walk, he tells them:

The truth was, in 1914, Germany doesn’t want war. Yeah, there’s an arms race, but it’s Britain who’s leading it. So, why does no one admit this?

That’s why. The dead. The body count. We don’t like to admit the war was even partly our fault cos so many of our people died. And all the mourning’s veiled the truth. It’s not “lest we forget”, it’s “lest we remember”. That’s what all this is about -the memorials, the Cenotaph, the two minutes’ silence-. Because there is no better way of forgetting something than by commemorating it.

The truth to these words is palpable. In every village square throughout Britain there is a stone column, inscribed with names. The Cenotaph is so finite. Its concrete defies questions. You cannot ask it: what did they die for?

As we lay wreaths, the liturgy intones that the war dead “made the ultimate sacrifice.” These words carry such gravity that you forget it was a conscript army. You dare not ponder: who sacrificed them, and for what cause?

Then, there is silence. So much silence that you cannot hear the echo: was it worth it?

Real memories are not fixed. They are fluid and living, constantly opening up new interpretations and interrogations. When you really remember, you pore over the details with others, seeking perspectives you missed, guided by a quest for greater understanding. You always want to know what you can learn from it, since the memory teaches something new to each moment.

But, as Alan Bennett’s character teaches us, that is not what happens with certain war memorials.

They are ways of remembering in order to make you forget.

There are, too, ways of forgetting to make you remember.

In 1988, the Israeli historian and Holocaust survivor, Yehuda Elkana, wrote an article for HaAretz called The Need to Forget. Not long after its publication, this article entered the new Jewish canon as one of the most challenging and profound commentaries on Shoah memorialisation.

In it, he warns against the danger that Holocaust consciousness poses to Israeli society.

He writes:

I see no greater threat to the future of the State of Israel than the fact that the Holocaust has systematically and forcefully penetrated the consciousness of the Israeli public.

Reflecting on the school trips to Yad Vashem, Elkana comments:

What did we want those tender youths to do with the experience? We declaimed, insensitively and harshly, and without explanation: “Remember!” “Zechor!” To what purpose? What is the child supposed to do with these memories? Many of the pictures of those horrors are apt to be interpreted as a call to hate. “Zechor!” can easily be understood as a call for continuing and blind hatred.

So, says Elkana, while the rest of the world may need to remember the Holocaust, the Israelis needed to learn to forget it. They needed to uproot the injunction to remember “to displace the Holocaust from being the central axis of our national experience.”

Elkana’s invocation of forgetting is also an invitation to remember. Forget the past in order to remember that we have a future. Forget the cruelties inflicted on our people in order to remember that we are greater than our misery. Forget the wars in order to remember the possibility of peace.

Elkana is not talking about an alternate reality where everyone wakes up tomorrow with amnesia about the last hundred years of history. He is talking about an active process of forgetting: forgetting by asking new questions and building new memories.

These are ways of forgetting intended to help you remember.

There are ways of remembering intended to make you forget.

But, the Torah tells us: remember in order not to forget.

What type of remembering would this be?

A full remembering, the type repeated twice by our parashah, the kind that forces you not to forget.

This remembering, then, must be one that always asks questions and returns to itself. A history that invites constant revision and ever wants to teach new lessons.

For the last sixteen months, Israel has been gripped by war. It has been unavoidable as its details have filled our news feeds and lives.

I know it is too soon to start the painstaking soul-searching involved in real remembering.

But it is plenty early enough to forget.

Already there are those who would like us to forget, so that they can eschew their own accountability.

How easily we can be made complicit in their acts of wilful forgetting.

So I have been considering how to fulfil the Torah’s commandment to remember.

I want to remember in fullness and complexity, always returning to new questions.

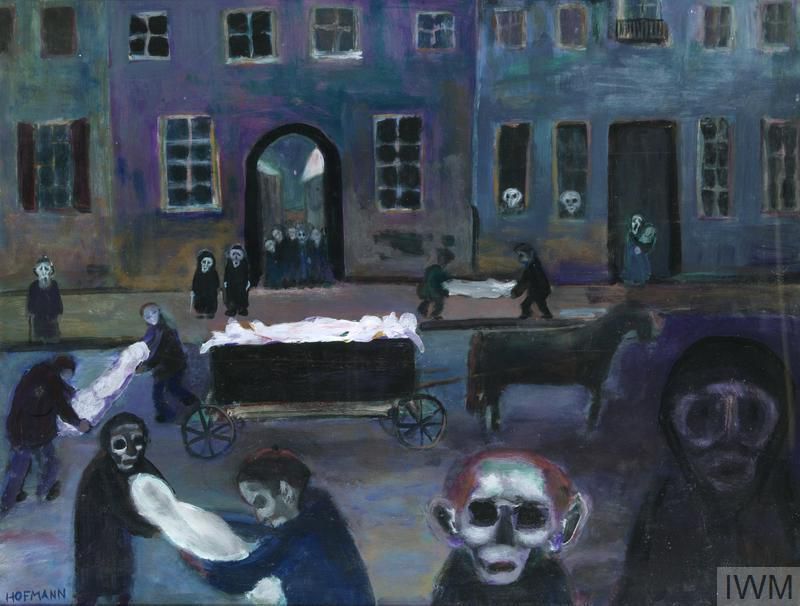

I want to remember all the suffering, for there has been so much suffering.

I want to remember all the dead. Every name. There are so many names.

I want to remember all those responsible. Every name. There are so many names.

I want to remember all the alternatives, because there have always been so many options, and there are still so many other ways.

I want to remember completely who I have been, who we have been, at best and at worst throughout this whole time.

It is too soon to remember.

It is too much to remember.

It is too painful to remember.

But, if we do not remember, we will forget.