“The history of a community, like the history of an individual, is marked by the recurrence of periods of self-consciousness and self-analysis. At such times its members consider their aggregate achievements and failures, and mark the tendencies of their corporation.”

These are the opening words of an essay that gave birth to our Jewish movement.

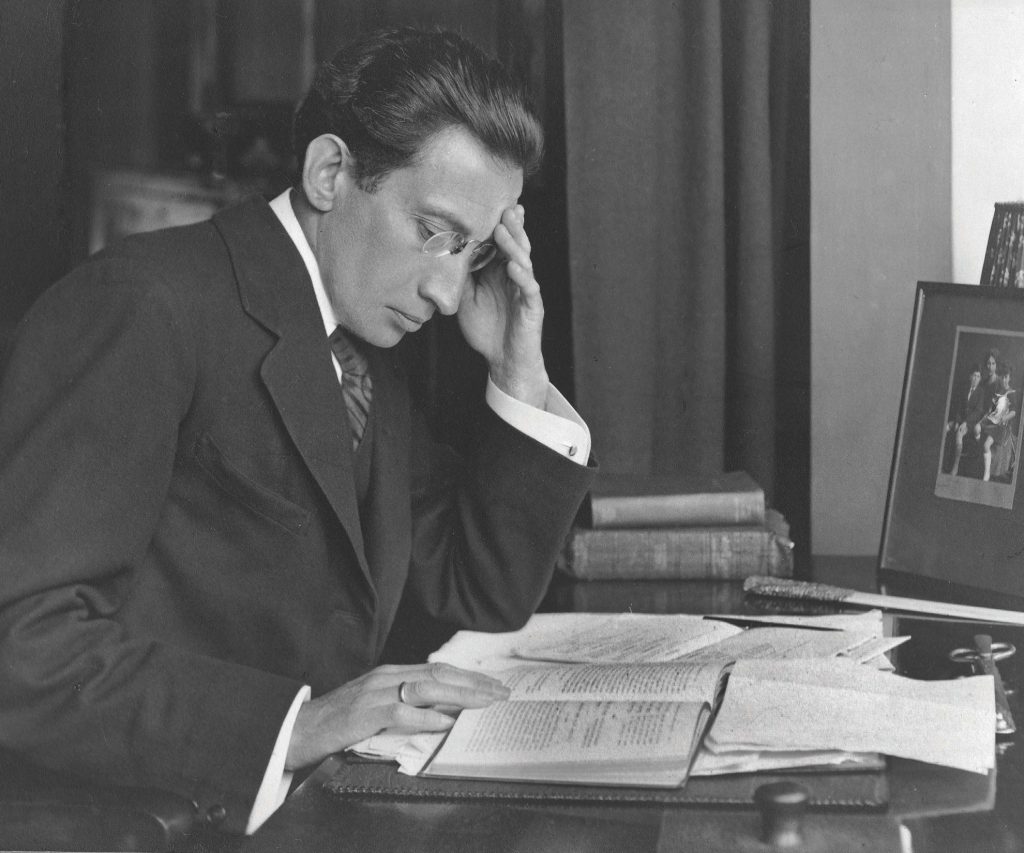

In 1898, a social worker named Lily Montagu published an essay in the Jewish Quarterly Review, entitled “The Spiritual Possibilities of Judaism Today.”

What this pioneering thinker asked of Jewish London was that it take stock of what it had achieved and what it wished to be. Only by giving an honest and sober account of where we were, could we imagine a better future for our Jewish life.

This is the perfect time to revisit that essay. We are forming a new movement, which will be far bigger and broader than Miss Lily could have anticipated, and may even soon make up the majority of British Jews. Is that not summons enough to the period of introspection Montagu required of us?

But, more than that, when you look at her essay from over 120 years ago, you can see that the issues Montagu wanted to address had much in common with the challenges facing us today.

Montagu was scathing in her perception of Anglo-Jewry. She accused it of “materialism and spiritual lethargy” and charged “that Judaism has been allowed by the timid and the indifferent to lose much of its inspiring force.”

Judaism, she felt, was supposed to be a great and inspiring system that would draw Jews closer to God and motivate its adherents to face the real-world challenges of the day. Instead, it had been captured by a lazy spirit that wanted nothing more than to assimilate, appease the establishment, and provide a lackluster imitation of religious rituals. Does that sound familiar?

Montagu assessed how London’s Jews actually lived. She called them “East End Jews” and “West End Jews,” but was clear that this was not just a geographical phenomenon. She was talking about class, culture, and background.

The “East End Jews” of her day were working class, poor, Ashkenazi immigrants. They were highly observant, but obedient to a fault. They followed along with the old words they already knew, but rarely spent much time thinking about what any of those prayers might mean for their soul. Their main motivation for practising Judaism was a combination of superstition and fear.

“West End Jews,” by contrast, were from higher classes and mixed ethnic backgrounds. They were materialistic, obsessed with status, and only attended synagogue because they thought it was more respectable to be Jewish than to have no religion at all. Yet, she said, by replacing real religion with possessions and status, they ultimately still had a vacuum where religion ought to be.

These types of Jews, as Montagu described them, don’t exist in the same way today as they did then. However much one might nostalgise the factory-working Jews of the Whitechapel shtetl or the days when Jewish aristocrats held drawing room parties in Maida Vale, that world is gone. Economic disparities persist, but far less visibly, and without entire Jewish cultures built around location and class.

She warned that, although the Jews of her age might be economically divided, they still had the same thing in common: their religion was vapid and empty. It was about having an identity rather than having a relationship with God. For both sets of Jews, Montagu argued, Judaism needed a complete spiritual revival.

Apparently, a great number of people agreed with her, because over the years and decades that followed, many came together to form congregations for exactly this purpose. Together, they made the Jewish Religious Union, which then became Liberal Judaism, and is now becoming part of Progressive Judaism.

Our Judaism has, indeed, been reinvigorated. We have opened up new approaches to liturgy, prayer, and worship. Synagogue teams come together to make sure that every Shabbat and festival is meaningful.

Montagu warned a previous generation that they would have to actually live Jewishly, or they would not be Jewish at all. Her prediction has come true, as some generations have just shaken off their roots, while others have decided to commit to Jewish life entirely.

One happy surprise is that, through the Liberals’ embrace of converts, we have Jews who are committed and educated in ways previously unknown in earlier generations. The dedication of converts has also inspired those who might have taken their Jewishness for granted to step up their game, learn more, and embrace their heritage.

Miss Lily did not just advocate for spiritual revival, but wanted to see Jews play a full role in the life of Britain. Full citizenship had only been granted to Jews a few decades previously, and Montagu wanted Jews to rise to the challenge.

Other communal bodies felt that the best thing for Jews to do was toe the establishment line, tell the government how wonderful they were, and hope that they would let us stay in the country without impeding on our religious practices. Our founders wanted us to embrace a more expansive sense of citizenship.

They wanted us to say: we live here, this is our home, and we have the right to change it. They wanted us not to grovel before power, but to make demands of it. They wanted us to ask ourselves “what does God require of our country?” and go about pushing for it.

This wasn’t something that belonged to one political persuasion. The intellectual leader, Montefiore was a capital C Conservative. The first Liberal rabbi, Mattuck, was a socialist who wanted the religious institutions to unite with the unions for revolution.

Montagu herself was a political Liberal. She was a suffragist and social reformer. She believed that the pursuit of peace and human rights were sacred commandments. She dedicated herself to alleviating poverty.

While politically diverse, our founders held in common a conviction that Jews could, in conversation with our God, make demands.

We could change the world. The world, too, could change us, and we should not be afraid of it or hide away in ghettos.

Montagu asserted that the youth were crying out for a Judaism that made moral demands and had something to say to their society. If their elders did not rise to the challenge, the next generation of Jews would vanish away into nothingness.

Montagu knew such Jews because her daily life was taken up as a social worker in London’s youth clubs.

I believe we are facing such a challenge today. Many Jewish young adults are looking at us, including in the movement she founded, and see a Judaism that is reluctant to take stands for fear of rocking the boat. They see a Jewish life where God is, at best, a nice accessory tacked onto a cultural centre. If we look honestly at our own institutions, can we deny their aspersions?

Throughout my twenties, I was one of these disaffected young people, bewildered by why my institutions were so ambivalent on the moral issues of the day, from massive inequality through catastrophic climate change to ongoing Israeli military occupation.

I felt acutely the absence of religious conviction in the establishment and in the institutions. There were pioneering rabbis who led the way on some issues, like gay rights, women’s equality, and refugees, but they were often marginal, and their impact could be felt only dimly in most synagogues. There was a gap.

In terms of our spiritual life, there were peer-led groups that tried to engage in serious prayer and text study, but you’d struggle to find any evidence for their existence in most synagogues.

I do not know how many young Jews fell by the wayside, but I stuck around. I had a strong sense, at least from my peers, that a better Judaism was possible. That we could speak out on social issues and we could have meaningful spirituality. That the Judaism of tomorrow might be more meaningful.

Now, in my thirties, I am a part of the establishment I railed against, and I feel that the issues facing Jewish youth are even worse. The moral and spiritual vacuum has only grown wider, and it looks even harder to fill.

I worry that the demands of our age for renewed spirituality and moral meaning are being quietly subsumed under a banner of “inclusivity.”

Inclusion is a positive and noble goal, but it must be inclusion in something. It must have real substance, if it isn’t just trying to market synagogue membership to the lowest common denominator while offering nothing and standing for nothing.

The challenge facing our movement is, I think, not so much to be broader, but to go deeper. We need to have a deeper relationship with God. We need to ask ourselves searching questions about what God demands of us. We need, as they did over a century ago, a thorough moral and spiritual revival.

In her essay, Montagu warned: “no fresh discovery can be made exactly on the lines of the past; the temperament of one generation differs from that of another.” We cannot apply Montagu’s methods in the same way today.

But we can ask the same questions that she did, and go through a serious process of reflection, as she suggested.

We can look together for new ways of revitalising our spiritual life, and put God at the centre of our synagogue.

We can work together to provide bold answers to the moral questions of our age. We can ask ourselves what God demands of Britain and hold up those prophetic clarions to our leaders.

These are the spiritual possibilities for Judaism today.

That is the spiritual challenge facing our new movement.

If we can rise to it, Progressive Judaism may yet last another century and beyond.