When I was a teenager, I went on some kind of away day with other Progressive Jewish youth.

The rabbi – I can’t remember who – told a story.

A woman dies and enters the afterlife. There, the angels greet her and offer her a tour of the two possible residencies: Heaven and Hell.

First, she enters Hell. It is just one long table, filled with delicious foods. The only problem is that they all have splinted arms. Their limbs are fixed in such positions that they could not possibly feed themselves. They struggle, thrusting their hands against the table and the bowl. Even if they successfully get some food, they cannot retract their arms back to their mouths. They are eternally starving, crying out in anguish. That was Hell.

Next, she enters Heaven. Well, it’s exactly the same place! There is a long table, filled with delicious foods, and all the people sitting at it have splinted arms. But here, there is banqueting and merriment; everyone is eating and singing and chatting. The difference is simply that, while in Hell, people only tried to feed themselves, here in Heaven they feed each other.

She ran back to Hell to share this solution with the poor souls trapped there. She whispered in the ear of one starving man, “You do not have to go hungry. Use your spoon to feed your neighbor, and he will surely return the favour and feed you.”

“‘You expect me to feed the detestable man sitting across the table?’ said the man angrily. ‘I would rather starve than give him the pleasure of eating!’

The difference between Heaven and Hell isn’t the setting, but how people treat each other.

At the conclusion of this story, one of the other teenagers – I can’t remember who, but I promise it wasn’t me – put his hand up and said: “But I thought Jews don’t believe in Hell?”

The rabbi shrugged and said: “True. It’s just a story.”

Years later, though, the story, and the resultant question, have stuck with me.

Was it just a story? Do Jews really have no concept of Hell?

The truth is complicated.

Among most Jews, you will find very little assent to the idea of punishment in the afterlife.

In part, that is simply because most of Judaism does not have a clear systematic theology. There is no Jewish version of the catechism, affirming a set of views about the nature of God, the point of this life, and the outcomes in the next.

Rather, Judaism holds multiple and conflicting ideas. On almost every issue, you can find rabbinic voices in tension, holding opposite views that are part of the Truth of a greater whole. We don’t mandate ideas, we entertain them.

So, a better question would be: does Judaism entertain the idea of Hell?

And the answer is still: it’s complicated.

Yes, it does. The story that rabbi told of the people with the splinted arms comes from the Lithuanian-Jewish musar tradition. It is attributed to Rabbi Haim of Romshishok.

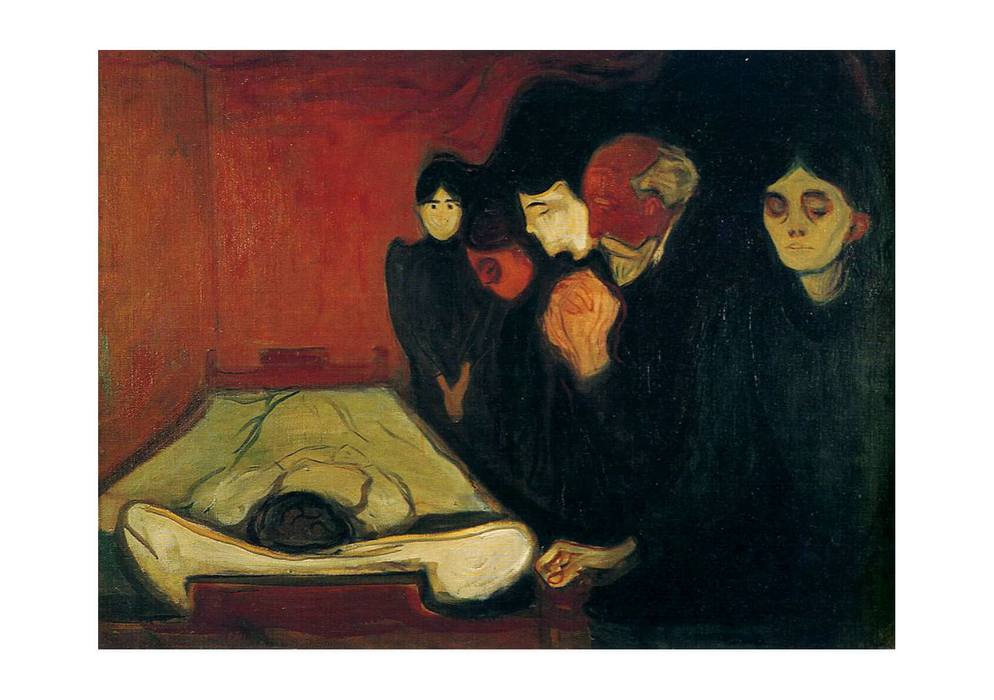

The idea of pious Jews going on tours of Heaven and Hell has a long history. In the Palestinian Talmud, a pious Jew sees, to his horror, his devoted and charitable friend die but go unmourned. On the same day, a tax collector, a collaborator with the Roman Empire, dies and the entire city stops to attend his funeral.

To comfort the pious man, God grants him a dream-vision of what happened to each of them in the afterlife. His righteous friend enjoys a life of happiness and plenty in Heaven, surrounded by gardens and orchards. The tax collector, on the other hand, sits by waters, desperately thirsty, with his tongue stretched out, but unable to drink. Where one gave in this life, he received in the next. Where the other took in this life, he was famished in the next.

This is a revenge fantasy. The story comes from oppressed people coming to terms with the success of their conquerors and the humiliation of the good in their generation.

The fantasy is powerful, and the motifs repeat throughout Jewish history. In almost every generation, you can find people pondering about how bad people will be punished and good people will be rewarded when this life is over.

But, with equal frequency, you can find Jewish scepticism about this view of the world. The Babylonian rabbis warn us not to speculate on what lies in the hereafter, for God alone knows such secrets. Our greatest philosophers like Rambam and Gersonides strenuously deny any concept of post-mortem torture.

These debates have persisted even into the modern era. During the Enlightenment, there were those who claimed that a rational religion could have no place for the primitive nonsense of Hell. Equally, there were those who said belief in divine retribution was the hallmark of a civilised belief system.

So where did the idea come from, asserted so confidently by that teenager on a day trip, that Jews have no concept of Hell?

The truth is it is very recent.

In surveys of attitudes, Jewish belief in Hell plummeted after the Second World War.

In all the revenge fantasies and horror stories that people could concoct about Hell, not one of them sounded as bad as Auschwitz.

There is no conceivable God who is cruel enough to do what the Nazis did. No such God would be worthy of worship.

We have no need to fantasise about freezing cold places filled with trapped souls, or raging furnaces. We need not imagine a world after this one where people are starved and tortured and brutalised. We know that world has already existed here on earth.

Isn’t Hell already here still? Doesn’t it still exist right here in this world for all those mothers putting their toddlers in dinghies hoping the sea will take them away from the war? Don’t those horrors already exist in for people working in Congolese gold mines or Bangladeshi sweat shops?

Hell is already here. It is war and occupation and famine and drought and slavery and trafficking. There is no need for nightmares of brimstone when people are living these things every day.

That was the point of the story that rabbi was telling us.

The difference between Heaven and Hell isn’t the setting, but how people treat each other.

We already live in a world of plenty. We have the flowing streams and gardens and orchards our sages imagine. But, like the inhabitants of Hell, we are pumping sewage into the streams, turning the gardens into car parks, and logging the orchards for things we do not need.

We are sat before a fine banquet where there is enough for everyone, but half the population are not eating while a tiny minority are engorged with more than they need. We are living the vision laid out in the parable.

Yes, this world is a Hell, but it could be a Heaven too.

The difference between Heaven and Hell isn’t the setting, but how people treat each other.

Look at all that we have. Look at the support we can give each other. We may have splinted arms but all we need do is outstretch them.

We have the capacity to annihilate all hunger, poverty, and war. We really could end all prejudice and oppression. This planet could be a paradise!

And, if we know that we can make this world a Heaven, why would we wait until we die?

Shabbat shalom.