“It makes no sense to hate anybody. It makes no sense to be racist or sexist or anything like that. Because whoever you hate will end up in your family. You don’t like gays? You’re gonna have a gay son. You don’t like Puerto Ricans? Your daughter’s gonna come home Livin’ La Vida Loca!”

This quotation is so erudite, you may wonder which ancient sage said it. That was in fact, the comedian Chris Rock, in his 1999 “Bigger and Blacker” set.

I must have been about 10 when I heard that line, but it has always stuck with me. Over the years since, I have watched it become true. The world is so small that whatever bigotries someone holds, the people they hate are bound to end up in their own homes.

Recently, I realised that this had happened to me. I hope I am not much of a hater, but a friend pointed out to me how much I used to make jokes about Surrey. I used to say that we should saw around the county lines of Surrey and sink it into the sea, drowning all the golf courses and making a shorter trip for Londoners to the beach.

Now, here I am, eating my words. I am about to marry a man from Surrey and have all my in-laws in Surrey. I’m the rabbi for a congregation in Surrey, and looking to move as soon as I can to Surrey. That thing I hated, even in jest, is right here in my family and inside of me.

I had some terrible stereotypes that everyone who lived here was a tax-dodging, fox-hunting billionaire. They weren’t grounded in reality. They were just about my own fears, projected onto people I had never met.

Chris Rock was right. Whoever you hate will end up in your family.

More than that: whoever you hate is already something inside of you.

All of us can do it: we can stereotype, generalise, and project all our antagonisms onto a group as a way to cast off all the fears we have about ourselves. What do we call someone who captures all this externalised hatred? A scapegoat.

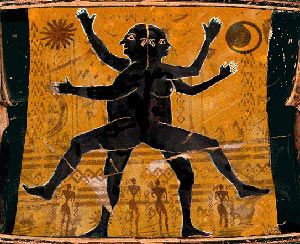

In this week’s Torah portion, we read about the original scapegoat. As part of the rituals for collective atonement, Aaron the High Priest gets two goats and brings them into the tabernacle. They pick straws for the goats.

The lucky one is to be sacrificed for God. Onto the lucky one, Aaron ceremonially transmits all the sins of the Israelites, then chases it out into the wilderness. As it scarpers off, the scapegoat symbolically carries away all of the Israelites’ misdeeds.

The biblical narrative describes a psychological trick we can all play on ourselves. When we are ashamed of something inside ourselves, we take all that fear, turn it into hatred, and throw it at whatever unwitting bystander will carry it.

Is this not precisely what Britain has been doing to trans people?

Gender is changing. The roles of men and women are shifting dramatically. There are so many new ways to live gender, to express ourselves, and to talk about our identities.

Rather than embrace these changes and think about what opportunities they can afford us all to be more free, reactionary parts of British society have whipped up a concoction of bigotry and thrown it all at trans people. Every anxiety our bigots have about gender has been exaggerated and projected onto one small part of the population, who have been turned into monsters through these prejudiced eyes.

It makes sense that people will find social changes scary and destabilising, but why should trans people bear the brunt of those fears?

A few years ago, I went to hear a panel of esteemed Jewish leaders give a retrospective talk about the ordination of gay, lesbian, bi and trans rabbis. On the bimah was Rabbi Indigo Raphael, Europe’s first openly trans rabbi.

In his opening words to the congregation, Rabbi Raphael proclaimed: “I am a transgender man. I am not an agenda; I am not an ideology; and you can’t catch trans by respecting my pronouns.” The room immediately erupted into applause.

He should not need to say it. He shouldn’t need to defend his own existence, but such is the level of moral panic in parts of Britain that he has to assert his right not to be scapegoated before he can even teach Torah.

In the last few weeks, trans people have been subjected to legal rulings and government decrees that may make their lives unlivable and keep them from basic participation in public life. Like the goats of the ancient world, they are being cast out into the wilderness to carry away all of people’s fears.

It should not be this way.

When we feel like scapegoating others, the best thing to do is look inside ourselves. We need to face our fears and work out why others bother us. The chances are, it’s something in ourselves that we’re not happy with, and when we need to get right with our own souls.

When we get to know those we “other” we get to know ourselves better. And when we realise we can like the difference in others, we learn more about what we can like in ourselves.

Reflecting on this, Margaret Moers Wenig, an American Reform rabbi wrote an essay called “Spiritual Lessons from Transsexuals.” She talks about how knowing trans people has enriched her own spiritual life.

Interacting with trans people, Rabbi Wenig says, has taught her that all of us can craft our bodies as we will; we are all more than just our flesh and blood; we have living souls that can differ from others’ assumptions; that only God knows who we truly are. These are wonderful lessons that can only be learned when we turn away from fear and embrace curiosity.

They chime with my own experiences. At first, knowing trans people made me question myself. If gender is something we can change, am I really a man? With time, seeing other people embrace their gender and become who they are has made me feel far more happy in my own gender. I am a man, and I like being a man, and I like being an effeminate man.

When we turn away from fear, we see that we have no need for scapegoats. The parts within us don’t need to be divided up so that some are holy and others need to be chased out into the wilderness. Every part of us is for God.

The world has more than enough hate. It’s time we swapped it for loving curiosity.

After all, Surrey, it turns out, is rather lovely.

Shabbat shalom.