As you know from all the advertising hype, there is a film out at the moment that deals with some of the most complex moral and philosophical questions of our time. It is already touted to win many awards, and has spurned fantastic conversations about truth, ethics, and politics.

I’m talking, of course, about Barbie.

Barbie already holds such a sentimental place in my heart. While the other boys liked wrestling, Fifa and war toys, I just wanted to play with my dolls’ hair.

I know, you’d never guess it. The butch man you see before you was once obsessed with the Dreamtopia Mermaid Barbie.

So, last week I did my duty as a good consumer, and went to the cinema for the first time since Dead Pool 2 came out. A lot has changed since I last went to the movies five years ago, and it seems that now everyone dresses up as the characters in the film. I was thrilled to get out my Ken costume, which I never knew I would have a use for.

During the film, I laughed, I cried, I reminisced. And as I left the theatre, I thought: “I’m sure I can squeeze a sermon out of this.”

Yes, that’s right, welcome to your Shabbat morning dvar Torah on the theological metaphysics of Barbie World.

Don’t worry if you haven’t seen the movie: I promise that will not help this make any more sense.

To help put this into perspective, I’ll give a quick summary of the storyline. Margot Robbie is a Barbie girl, in a Barbie world. Her life in plastic is fantastic. She is driven by the power of imagination. Life is her creation.

In Barbie World, a doll can be anything. A President, a marine biologist, a Nobel Laureate, a mechanic, a pastry chef, or a lawyer. Even a rabbi.

But then a great intrusion comes into Barbie’s dream world. She finds that she now has cellulite and existential dread. This plastic world of fantasy suddenly starts to turn into something… horrifyingly human.

Barbie therefore must travel to the world in which people play with her, to find out what is going on in the world of real girls.

The result is distressing. It turns out that the real world is defined by misery and hatred, and, in this world, girls absolutely cannot do anything they want.

I am interested in the interplay between these two worlds. In the plastic world, anything is possible, but none of it matters. In the human world, everything matters, but nothing is possible. These two versions of reality conform to two popular narratives.

The first is that this world is just a simulation. That view is being propogated right now by Elon Musk and Neil deGrasse Tyson. It says: none of this is really real. Our world is like Barbie World: it is someone else’s fantasy that we are stuck in, playing roles. Anything is possible, but only the terms of the magnificent computer directing our lives.

I understand why that idea is so appealing. The word is a mess. There is something reassuring about believing that none of it is really happening and it’s all out of our control.

Although today this idea can appeal to new innovations in quantum physics, it is actually a very old idea. In the 17th Century, Irish philosopher Bishop George Berkeley promoted a similar philosophy, called “immaterialism.” We are all, he said, simply ideas in the mind of God.

Berkeley continues: if this world is just an illusion, your only duty is to conform to the role you have been given. You must blindly follow authority. We must all submit to the law and do as we are told.

Barbie has been told that she must fulfill the stereotype she has been molded in, and she has no choice but to accept it.

We need not wonder why a group of billionaires would like us to think this way. If reality is just an illusion, we just have to accept our place. And there’s no point resisting it, because the script has already been written, and none of it means anything anyway.

But the alternative world of the Barbie film – the human world – is not compelling either. In the human world, everything is made up of futile facts. It’s all real, and there’s nothing you can do about it. The grass is green. People grow old. You will get cellulite. Patriarchy is inevitable. It is all meaningful, but its only meaning is that everything is deeply, existentially depressing.

This is also a very popular worldview right now. It is best encapsulated by conservative talk show host, Ben Shapiro, whose dictum is “facts don’t care about your feelings.”

And that idea can be seductive too. The world is changing so fast and so much. Why can’t everyone just accept that everything is the way it is and stop moving so much?

Ben Shapiro offers brutal reality as an antidote to too many ideas. You think this world is horrible? Tough. You’re lumbered with it. This vulgar materialism, that says everything just is the way it is and nothing will ever change, is just as reactionary as the immaterialism that says nothing matters.

So, let’s get to the point. What does Judaism have to say about this?

Is this all just a simulation so that we are all just living in a fantasy world?

Or is this all the cold, hard, truth of reality?

In the 20th Century, Jewish philosopher Ernst Bloch tried to offer a third way. Bloch was a religious socialist from Germany, who fled around Europe as the Nazis took power everywhere he went. For him, it was deeply important to develop a view of the world where the unfolding horrors of fascism could be stopped. Any metaphysics that kept people from changing their circumstances had to be resisted.

Bloch turned to great religious thinkers of the past to remind people: it doesn’t just matter what is; it matters what could be.

This world is real, and the one thing we know about reality is that it is constantly in flux. Everything is as it is, and everything will be different.

Everything is subject to change. Everything that is is also something else that is not yet.

Ice turns into water turns into steam. Acorns become sprouts become mighty trees. People grow and age and learn. Societies progress from hunter-gatherers out of feudal peasantry and move to abolish slavery.

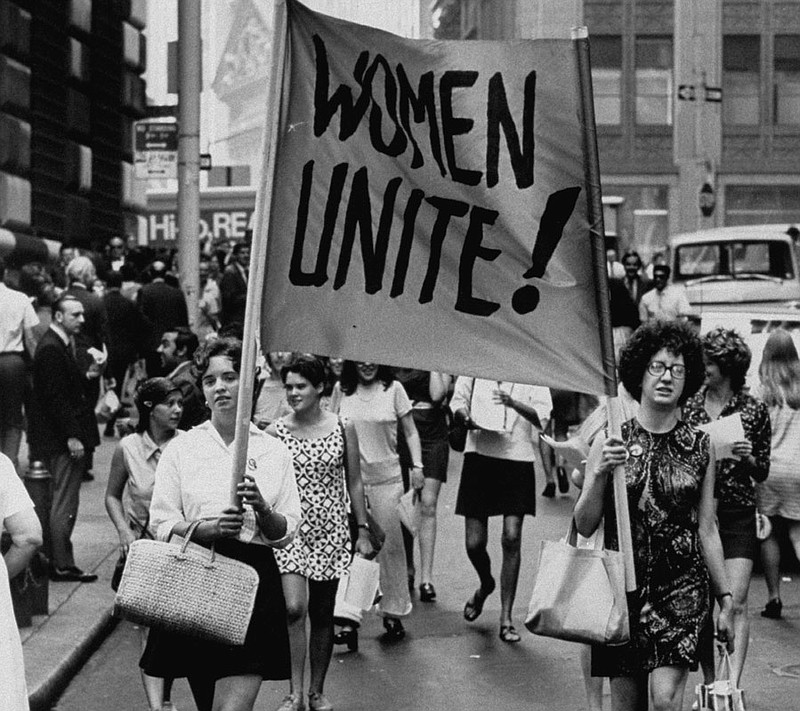

In all of their forms, these things are exactly what they are, and are also everything they could be. They are only what they are for a brief moment as they are becoming something else. The movement of water into ice is just as real and possible as the movement for women’s equality.

To put it another way: this world is real, but it doesn’t have to be. There are so many other very real worlds we could live in.

Ernst Bloch would have loved the metaphysics of Barbie World. It doesn’t just leave us with the misery of the real world or the pointlessness of the fantasy world. It shows us that both worlds speak to each other. The real world can become more like the fantasy world, and the fantasy world can become more like the real one.

This is the Jewish approach. Our task is not just to accept the world but to change it. As Rabbi Jonathan Sacks used to teach: “faith is a protest against the world-that-is by the world-that-ought-to-be.” Faith, for Sacks, is the demand that this imperfect world could be more like the utopian one. Like Bloch, Sacks talked about Judaism as the “religion of not-yet,” always moving towards what it would one day be.

This is what animates the Jewish religious mind: the possibility that this world, here and now, could be transformed into the vision we have of a perfected Paradise.

So, how do we get there?

Once again, we have to take our inspiration from Barbie. When Barbie wanted to get from the fantasy world to the real one, first, she got in a car, then on a boat, a tandem, a rocket, a camper, a snowmobile, and finally a pair of rollerskates.

To bridge the gap between worlds, all she had to do was put one foot in front of the other.

That is what we must do too. We must take small steps in our pink stilettos, and set out towards the real fantasy world.

Utopia already awaits us.

Shabbat shalom.