This is the week of our Torah dedicated to love stories. Our religious texts often contain laws or stories of struggle, but this is a unique reprieve, in which we are offered some romance.

At the beginning of our parashah, Sarah dies, and Abraham bargains for the perfect burial site. He wants to ensure her burial arrangements are in exact order. Later, he will be buried beside her, so that they can be joined forever in the hereafter.

The Talmud clearly picks up on how sweet these negotiations are, because it embellishes a story of what happened many centuries after they had died. Rabbi Benah was marking burial caves. When he arrived at the Cave of Machpelah, where Abraham and Sarah were buried, he found Abraham’s faithful servant Eliezer, standing before the entrance.

Rabbi Benah said to Eliezer: “Can I go in? What is Abraham doing?”

Eliezer replied: “Abraham is lying in Sarah’s arms, and she is gazing fondly at his head.”

Rabbi Benah said: “Please let him know that Benah is standing at the entrance. I don’t want to barge in during a moment of intimacy.”

Eliezer said: “Go on in, because, in the higher world that they inhabit, souls no longer experience lust. All that is left is love.”

Benah entered, examined the cave, measured it, and left.

It’s such a beautiful story. It teaches what an ideal relationship should be, where a couple loves each other long after death.

Perhaps, most significantly, it tells a story of mature love; of what happens when relationships really do last, and people carry on loving each other until their last days. I think we all know of such couples, but their stories rarely appear in our culture. We get romantic comedies. We get depictions of what love is like when it’s just starting out, but not so much about how it endures. Our media shows the hero get the girl, but not how they make their relationships work.

Don’t get me wrong. I love a good rom com. Yes, I did think Ten Things I Hate About You was a masterpiece when I was a teenager. And I absolutely did binge watch both series of Bridgerton on Netflix.

They all follow a predictable plotline. Two loveable heroes, and you’re rooting for them both. They encounter a tribulation. They overcome an obstacle. There’s a grand gesture. They realise they’re supposed to be together. In the end, there’s a wedding and they all live happily ever after.

In a way, that’s the story that we find immediately after Sarah’s funeral. Abraham realises that Isaac needs a wife. He sends out a search party, led by ten camels. He sets a test: whichever woman offers water to the camels by the well is the one meant for Isaac.

Immediately, we root for Rebekah. She is beautiful. She’s strong. She’s hard-working. She offers to feed all the camels, and rushes back and forth, drawing water from the well, feeding an entire herd of camels. Obstacle surmounted, we get our grand gesture. She is presented with a huge gold nose ring and two huge gold bracelets. She accepts. Their families rejoice. Everyone agrees that this was arranged by God.

There’s just one snag to reading a romantic comedy into all of this. The hero in the story isn’t Isaac. The man who goes out with all the camels, sets the challenge, starts the relationship, and makes the big gesture, is Abraham’s servant, Eliezer. By rights, if this were a love story directed by Richard Curtis, the wedding would be between Rebekah and Eliezer!

Isaac isn’t even involved. They’re engaged and the deal is done before the couple have met. Rebecca doesn’t know what he looks like. When Isaac later comes clopping along on his horse, Rebecca asks who it is. We have to hope that she was impressed, but we can’t be sure.

All we know is that, once married, Isaac feels comforted after the death of his mother. The heroin in our story, at the end, is reduced to a replacement mum for her husband. A love story this is not.

But, do they at least go on to have a happy marriage? Of course not. They were forced together as strangers as part of an economic arrangement.

In the entirety of our Torah, they never say two words to each other. They just pick favourite children and pit them against each other. They trick each other, lie, and form an unbelievably dysfunctional family.

The whole thing is a nightmare. It’s far more Silent Hill than Notting Hill.

This could never have been a love story! We’d never have got Sandra Bullock narrowly missing out on an Oscar for her heart-wrenching performance as Rebekah. We can only wish for Sacha Baron Cohen bumbling as a comedy father Abraham.

90s cinema didn’t invent romantic love, but it was far closer to its origins than Isaac and Rebekah were. The idea of romantic love, as we know it, was born out of the Enlightenment.

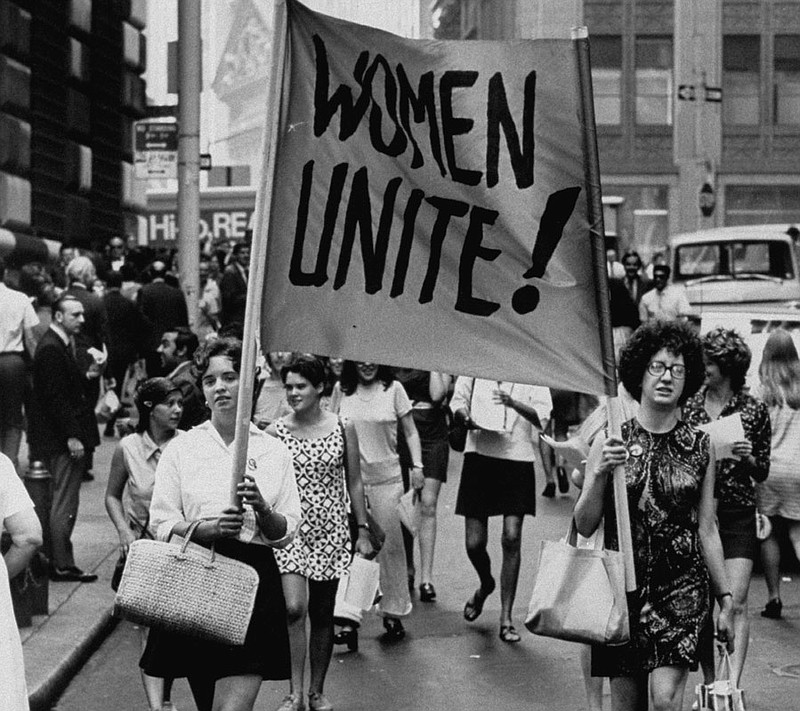

During the Age of Reason, philosophers had the wild idea that partnerships between people might be based on more than just combining property and keeping families happy. They suggested that marriage might not just be a way for nobility to make treaties between nations, but borne of a deep feeling common to all people. They even offered up the radical idea that women were people, and might have an opinion on their relationships too.

In those heady days, Judaism split between those who accepted the ideas of the Enlightenment, and those who did not. We, who embraced those fantastic ideas of equality, became the Movement for Reform Judaism.

As we accepted the ideas of love between equals, our rituals and ceremonies have progressed with us.

In a traditional ceremony, the woman is acquired with a ring. The ring is, in its origin, a symbol that the woman has been purchased. When Rebekah received her nose ring and bracelets, she was effectively accepting the shackles of her new owner.

In our ceremonies, both partners to the wedding mutually acquire each other, or even forgo rings in favour of an alternative symbol of equal partnership. Both partners encircle each other under the chuppah, showing their shared space.

Whereas in a traditional ceremony, a woman may remain silent, Reform weddings require explicit consent from both parties. Both read their vows, and some couples choose to produce their own.

This may now seem obvious and intuitive, but it is only because the ideas of the Enlightenment have taken such hold. Love – the idea that people can be equal and caring partners – has had to be won.

Love is really a Reform value. It is something special to our movement. Our ancestors spent centuries fighting for the idea of meaningful love, so that we could celebrate it today in all its forms. You can only really celebrate love in a place that really believes human beings are equal.

And that is why Sarah, holding Abraham in her arms, gazing lovingly at his head, joined with him in an immortal embrace, was the first Reform Jew.

Shabbat shalom.

Parashat Chayyei Sarah, 5783