Hello, I am back from my holidays in Spain and France. I brought you all back some lovely little trinkets from The Louvre. Just don’t tell anybody you got them from me.

I spent my holiday thinking about how easy it is for me to travel, and how impressive my journey would seem to previous generations. I wondered about what it was like in earlier centuries for people travelling the world.

In 1532, a great king travelled across the Atlantic to meet a previously unencountered tribe. The king was, in some ways, disgusted by the society he encountered, which was rife with inequality, governed by a despotic ruler, near constantly in a state of war, and yet to develop serious hygiene practice.

He was, however, impressed by the luxuries he saw in the local king’s palace, and intrigued by the sophisticated religious culture the people had developed.

The indigenous people went by many names, but the locals called themselves “the English.”

That’s right, in the early 16th Century, an Aimoré king travelled across the Atlantic from Brazil to the court of King Henry VIII and attended the palace as a distinguished guest.

We are used to thinking of international travel in the Tudor Age as something that voyagers from England, Portugal, Italy and Spain did to the so-called “New World,” but plenty of people also went the other way.

Recently, the historian Caroline Dodds Pennock released a book called On Savage Shores, which looks at the people who travelled from the Americas to Europe. They gave their own verdicts on European society, often quite damning of its inequality and sanitation.

Dodds Pennock is well aware that, by telling these stories, she is reversing the gaze. To the indigenous travellers, it was the Europeans who were the strange exotic outsiders.

If this feels surprising to us, it is probably because we are so in the habit of imagining that rich colonising men go out and see the world, but we don’t often think of those same men getting looked at by the world.

There is a reason that Abraham’s story of setting out from Haran was so compelling to its ancient listeners. Most people did not travel more than a mile from their own town. The world beyond was a mysterious and exciting place. They could only hear about the journeys, people, animals, and plants that others saw from testimonies, like those given in the Torah.

Abraham’s trek belongs, then, in a similar category of travel literature to Homer’s Odyssey, which was likely told as an oral story, and then committed to writing at a similar time to Abraham’s journey in the Torah. Odysseus encounters singing sirens, multi-headed monsters, and lotuses that make you forget your home.

Abraham, on the other hand, goes on a thousand-mile hike with no less than the One True God. Along the way, he marries a foreign princess, meets the king of Egypt, does battle in the Dead Sea with local lords, and meets angelic messengers over a meal.

This story must have remained compelling to many generations of Jews afterwards. Medieval Jews were used to living in one place. They may have been visited by merchants and Crusaders. Some may have gone away on fixed routes as merchants, and there were times when whole communities had to leave in haste.

But the idea that one of their own – the first ever Jew – went out on such an exciting adventure would have been thrilling to the Torah’s audience.

We know much of what other people thought of the Jews they met. Medieval accounts describe Jews almost as a people fixed in time; like a noble relic from a simpler age. The European travellers who encounter Jews treat them with a combination of scorn and exotic interest. In that sense, the Jews of Europe had more in common with the colonised people of the Americas, who were similarly treated as foreign oddities.

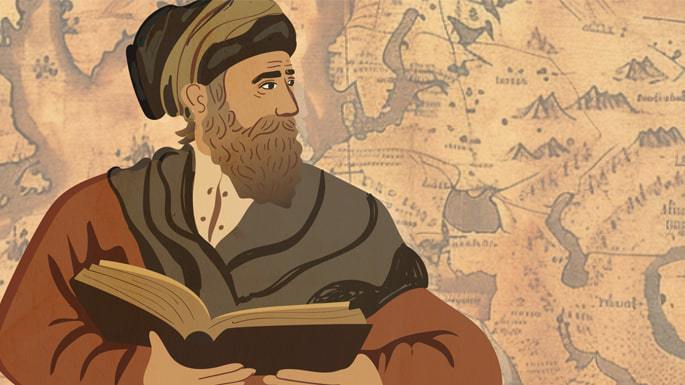

Bucking the trend, however, was a fascinating figure of the 12th Century, called Benjamin of Tudela. Born in the Spanish kingdom of Navarre, Benjamin went out on a journey tracing the Jewish communities of southern Europe, northern Africa, and south west Asia.

He took a long route on pilgrimage to Jerusalem that brought him through countries we would know today as Italy, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and Iran. He seems also to have travelled around the Arabian peninsula, looking for the Jews of Africa, but never reaching the Gondar region of Ethiopia, where he might have found them.

Benjamin recorded all of his encounters in Hebrew, in a book called Sefer HaMasa’ot, the Book of Travels. His chronicles were so fascinating that they were reproduced over many centuries, and translated into Latin and most European languages.

Today, Benjamin’s records have attracted scholarly attention, not least because they subvert our expectations of who goes exploring and who gets explored. Benjamin writes with fascination and joy about the Pope in Rome and the Caliph in Baghdad.

Most importantly, when Benjamin meets Jews in other countries, he is at once meeting his own people and meeting people entirely different from himself. When he sees how other Jews do things differently, he feels joy in diversity. When he sees Jews doing well, he feels pride; and when he sees other Jews in a persecuted condition, he suffers with them as his own.

This is the great blessing of Benjamin’s travelogue: he can see the world through two sets of eyes – as both an outsider and as an insider. When he travels, he is never quite the colonialist going out to comment on others, but he’s never just looking at his own people. This gives him an impressive position of humble curiosity.

As British Jews, we may learn to do the same thing.

We have a blessing by dint of our position. That blessing is a special ability to look at the world through multiple sets of eyes.

We can, indeed, look at the world through European eyes. We are Europeans, and we belong here. We can see England as it is imagined by the English, where this island is the centre of the world, its monarchs the most illustrious, its culture the highest human attainment. We should not shy away from seeing the best in Europe: we are part of it, and there is much to love.

We can also, if we choose too, see this continent through outsiders’ eyes. We can see its flaws, its delusions of grandeur, and its odd habits. We can be the best possible internal critics of our country, because we understand what it is to belong, and what it is to feel like we do not.

The danger in either of these sets of eyes is that we turn them into a haughty gaze. Like the early colonialists, we have the capacity to see every other culture as backward and barbaric, or its people and lands as subjects for exploitation. Inverting the gaze, we might come to see the Europeans as horrible invaders, without directing the critical lens on ourselves.

But if, instead, we can approach the whole world with modesty, we can see every nation and every place with loving curiosity. With humility, we can see ourselves as fellow travellers with everyone else, discovering this wonderful world together.

If we can do this, then, like Abraham, we may truly learn to walk with God.