The things you hate in others are the things you hate in you.

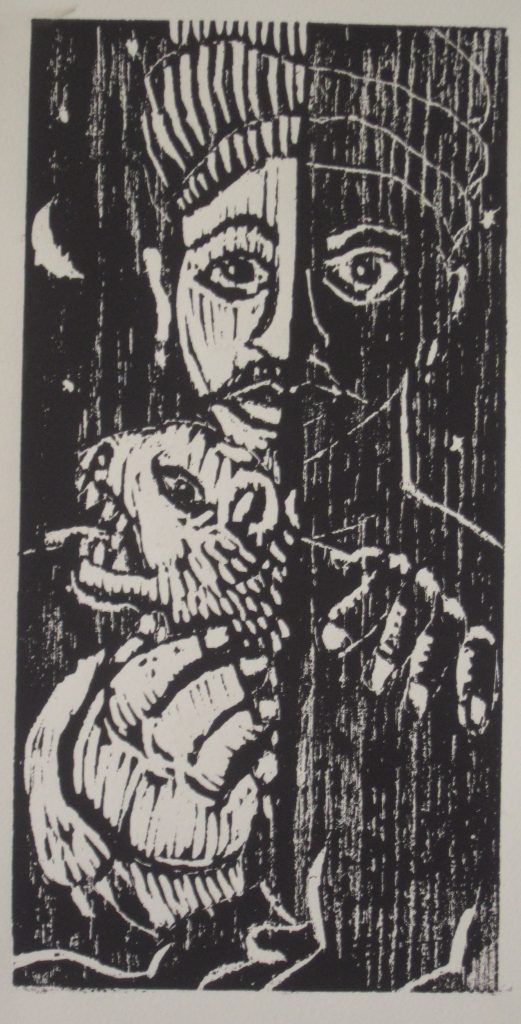

All too often, we create monsters out of others because we fear there is something monstrous in ourselves. We turn outsiders into figures of hate because there is something we cannot stand inside ourselves.

In the Talmud, Laban is called the trickiest of tricksters. He came from a family of tricksters, in a town of tricksters, and all he ever did was trick.

Now, Laban was indeed a trickster. He was a thief and a manipulator. But was he really the worst of the worst? Most importantly, was he really worse than Jacob?

Laban did wrong, multiple times. He behaved appallingly.

From the outset, he took Jacob in on false pretences.

Laban told Jacob that, if he worked for him for seven years, he could marry his younger daughter, Rachel. Jacob adored Rachel, and was willing to do anything for her, so fulfilled his obligations.

Then, on the day of the wedding, Laban swapped out Rachel for her older sister, Leah. Laban made Jacob work another seven years to marry the woman of his dreams.

Once Jacob had married both daughters, Laban continued to trick and deceive. He kept trying to rob Jacob, arbitrarily changing the terms of the contract.

Jacob says that Laban had tried to swindle him with new rules ten times. In our midrash, the rabbis say it was in fact a hundred. Laban absolutely stole, and absolutely tricked.

Now, can we compare this to Jacob?

Only last week, we saw how Jacob tricked his father and his brother to steal from them. Jacob dressed up as his brother, pretended to cook like his brother, and stole his brother’s birthright. Jacob took advantage of his elderly father, who was going blind, to swindle him out of a blessing.

Jacob, too, stole and tricked.

To read the rabbinic tradition, however, you would think it only went one way!

The midrash bends over backwards to exonerate Jacob. It says that his father, Isaac, knew what was going on all along, and was only pretending to be deceived. It says that his mother, Rebecca, was given prophecy by God, so she knew what the future of her sons entailed. Throughout rabbinic commentaries, we get apologia for why Jacob was really right to receive the birthright, and why Esau would have been a terrible choice.

None of this is in the text. It is really a PR campaign to protect Jacob’s reputation.

Laban, by comparison, is subjected to thorough demonisation.

The rabbis say that Laban sought to kill Jacob, despite there being no evidence of it. They go further: Laban wanted to massacre the Israelites entirely so they would have no future. Laban wanted to subjugate the Israelites worse than Pharaoh ever could. The rabbis say Laban lived hundreds of years, and could think of nothing else but swindling Israelites throughout that entire time, motivated only by spite. They call him ugly, and stupid, and say he slept with animals.

Contrary to the plain reading of the text, our tradition turns Laban into a monster, with every flaw exaggerated to absurd degree. They warp him from being a simple trickster into a demonic tyrant.

Our rabbis’ goal is to divide the world into the two camps: the innocent and the evil. On the one side, they have Jacob, who, no matter what he did, can never be held accountable. On the other side, they have Laban, the pinnacle of malice. No matter what may have motivated him, Laban will always be depicted as a corrupt crook, lusting after the death and misery of others.

In fact, the crimes of Jacob and Laban were almost identical. Laban tricked; so did Jacob. Laban stole; so did Jacob.

There is a good reason why the rabbis would want to defend Jacob and castigate Laban in this way. Jacob is us. He changed his name to Israel and became the founder of the Jewish people. If Jacob is bad, so are we.

Laban is our enemy. If he can be excused, what does that make us? How can we be the good guy, if he is not the bad one?

Naomi Graetz, a scholar at Ben Gurion University, compiled all these sources and suggests that what is going on here is a classic case of negative projection.

We know that Jacob did those bad things. But, if we throw them all onto Laban, they no longer stick to us. By constructing Laban as a monster, we can feel assured in the positive self-image we want to hold.

This, she says, is what groups often do. They create “others” – people that they imagine to be different to them – so that they can throw at them the worst fears of what they themselves might be.

The things we hate in others are often, really, the things we like least about ourselves.

Hating others gives us an easy way to escape our own feelings of discomfort. If we can hate them, we don’t have to look too hard in our own mirror.

In mediaeval Europe, that was a big part of how antisemitism functioned. Jews were the “other” onto which their neighbours projected all their anxieties.

The Jews, according to the antisemitic imagination of the time, were usurers, stealing money from people. In the Middle Ages, most money-lenders were not Jewish. They were Christians. At this time, certain Christians were also becoming very wealthy as landlords and merchants. Rather than deal with it as a social problem shared by everyone, they racialised it. They turned it into a Jewish problem, so that they did not have to face it as their own.

Even the blood libel, a mediaeval conspiracy theory that Jews drank Christian blood, can be understood as projection. As part of regular Catholic services, they drink the blood of Jesus, in the form of wine. Clearly feeling some guilt about their own rituals, they thrust this fear onto the Jews. It is not us who drink blood, it’s them!

It is probably not a coincidence that the modern antisemitic trope of Jews ruling the world came about when the European empires were at their height.

Antisemitism was a way for Europeans to resolve their discomfort about who they were by turning it into hatred of someone else.

Still, if I only talk about how bad and racist others once were, I would be projecting. The point is not that they can do it, but that we can.

We are very capable of making demons where there are just people. We can just as equally project our own fear by turning it into hatred of others.

We need to remember that the world is not made of heroes and villains. Humanity cannot be divided up so easily.

If we look at the biblical story, as it appears in the Torah, Laban is not a monster. Nor is Jacob. They are just people. Flawed, messy, human beings, doing wrong, and making mistakes. They both did wrong. But neither of them were evil.

The Torah gives us a whole host of complicated characters. They are not models of perfect behaviour. They are not even moralising cautionary tales. They are just a reflection of reality: which is complex and scary. We learn best from our imperfect prophets.

Rather than trying to resolve our anxieties with hatred, let us look inside ourselves.

When you see something in someone else that you hate, ask: what is it in me that makes me feel this?

When another group seems like devils, ask yourself: are we really angels?

People will do wrong. All the time. They will mess up and cause pain in all kinds of ways.

Most of the time, we cannot change that.

But we can work on the things we can change in ourselves.

We can forgive the things we cannot change.

And if you accept that you are capable of harm, without it making you evil, you may be able to have compassion for yourself.

And you may find that you love yourself, after all.

You may see yourself the way God sees you. As an imperfect human who makes mistakes. Not a monster. Just a mess. A thoroughly lovable mess.

And if you can love yourself, warts and all, you may find you have less space left to hate others. You may find that you contain more compassion and empathy than you knew.

The things we hate in others are the things we hate in ourselves.

The things we love in ourselves, we can love in others too.

Shabbat shalom.