Fifteen years ago, the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie gave a powerful speech, in which she warned about “the danger of the single story.” This, she says, is how you create a single story: “show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become.”

Because of the single story told about Africa, Westerners knew it only as backwards, poor, and disease-ridden. They did not know how diverse, interesting and resilient Africans were. They did not know that Africans were not, in fact, one people with one story, but billions of people with billions of stories.

She warns her listeners: “The consequence of the single story is this: It robs people of dignity. It makes our recognition of our equal humanity difficult. It emphasises how we are different rather than how we are similar.”

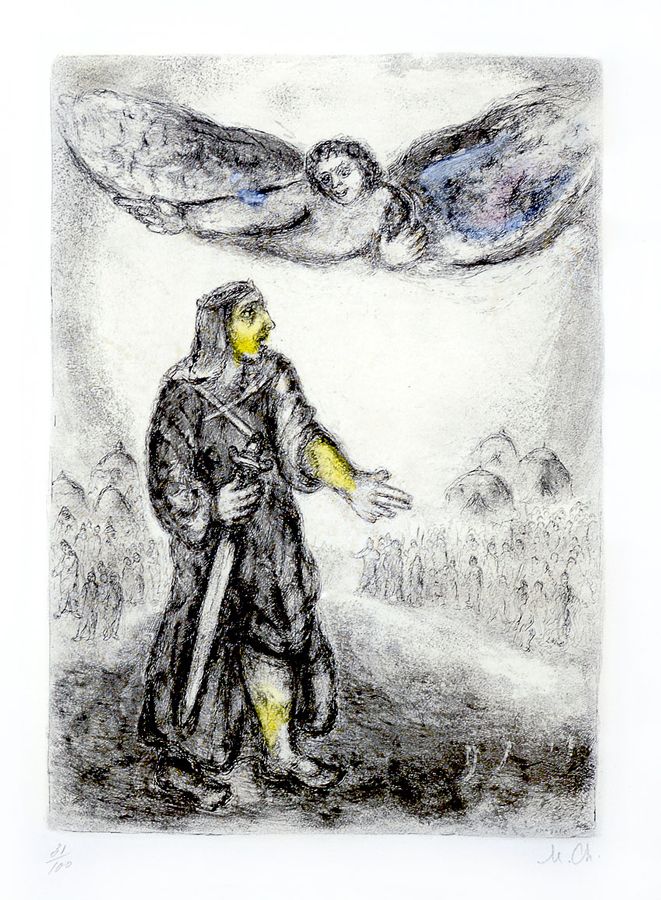

In the book of Joshua, we are presented with a single story about the Israelites and their enemies. In our haftarah, Joshua gathers the tribes of Israel at Shchem and presents his account of the conquest of Canaan. He declares:

You crossed the Jordan and came to Jericho. The citizens of Jericho fought against you, as did also the Amorites, Perizzites, Canaanites, Hittites, Girgashites, Hivites and Jebusites, but I gave them into your hands. I sent the hornet ahead of you, which drove them out before you—also the two Amorite kings. You did not do it with your own sword and bow. So I gave you a land on which you did not toil and cities you did not build; and you live in them and eat from vineyards and olive groves that you did not plant.

In Joshua’s single story, the Israelites are a nation united at war. They all came over at once and went to conquer the land of Canaan. Their enemies were diverse in name but unified in mission. In the list of warring tribes that came up against the Israelites, there is no distinction. Every one of them fought the Israelites. Every one of them lost. By God’s miraculous deeds, the Israelites took over the entire country, and now they have a whole land, ready-made, for them to inhabit.

But wait. There is a flaw with this single story. Just as Joshua decrees that the entirety of these foreign nations has been wiped out, he also warns the Israelites not to mix with them.

All of these other tribes have been completely driven out of the land of Israel; all of them have been vanquished; now the only people left are the Israelites.

But even though the Israelites are the only people remaining, you must not marry the others; or get involved in their cultural practices; or go to their shrines with them and worship their gods.

The Jewish bible scholar, Rachel Havrelock, has written a book looking at why this contradiction is so stark. She suggests that, while the Book of Joshua would love to tell a single story of unanimous military victory, it cannot get away from what the people see with their own eyes.

In reality, all the nations that the Israelites “drove out” are still there. The Israelites are still meeting them, marrying them, striking deals with them, and fraternising with them.

Joshua is putting together the war story as a national myth to bring the people together. In his story, the Israelites must be one people and so must all their enemies. Victory must be total and war must be the only way.

In fact, Havrelock finds that there are lots of contradictions in the book of Joshua. It says that the nation was united in war, while also describing all the internal tribal disagreements and all the rebellions against Joshua.

It says that they took over the whole land, but when it lists places, you can clearly see that plenty of the space is contested, and that the borders are shifting all the time. It says they took over Jerusalem, and also says that it remains a divided city to this day.

So what is the reality? Archaeological digs suggest it is very unlikely that the conquest of Canaan ever happened in the way the Book of Joshua describes. The land was not vanquished in one lifetime by a united army. Instead, more likely, the Israelites gradually merged with, struck deals with, and collaborated with, lots of disparate tribes.

They were never really an ethnically homogenous group. They were never really a disciplined military. They were a group of people who gathered together other groups of people over many centuries to unite around a story. Ancient Israel was the product of cooperation and collaboration.

Our Torah takes all the different stories of lots of different tribes and combines them into a single narrative. That is why the Torah reads more like a library of hundreds of folktales than a single spiel.

But a government at war needs a single story. It needs to tell the story that there is only one nation, which has no internal division. It needs to tell the story that there is only one enemy, and that the whole of the enemy is a murderous, barbarous bloc. It needs to insist that the enemy must be destroyed in its entirety. It needs to tell the story that war is the only way.

Reality, however, rarely lives up to the single story that war propaganda would like us to believe.

Over the last few months, we have been bombarded with a single story of war. We are all at war. Not only Israel, but the whole Jewish people. We are all at war until every hostage is freed from Gaza. We are all at war until Hamas is destroyed. We are all at war and there is no other way.

But hidden underneath that story are other stories. Suppressed stories. Stories that suggest Israel may not be united in war.

There is the single story that Gaza must be bombed to release the remaining hostages.

There is another story. Avihai Brodutch was with his family on Kibbutz Kfar Aza on October 7th. He survived. His wife, Hagar, was taken hostage, along with their three children, aged 10, 8 and 4. His whole family and his neighbours were taken hostage.

Only a week later, at 3am, Avihai took a plastic chair and his family dog, and went to launch a one-man protest outside the Israeli military offices. He insisted that blood was on Bibi’s hands for refusing to negotiate. He said that Netanyahu was treating his family as collateral damage in his war. He initiated a rallying cry: “prisoner exchange.”

This has become a demand of Israeli civil society. They will swap Palestinian prisoners for the Israeli hostages. This was achieved, when 240 Palestinian prisoners were swapped in return for 80 Israelis and 30 non-Israelis captive in Gaza.

There are still over 100 hostages in Gaza. There are still around 4,000 Palestinian political prisoners in Israeli jails. Around 1,000 are detained indefinitely without charge. Around 160 are children.

It is simply the right thing that Hamas should release the hostages. It is also simply the right thing that Netanyahu should release the Palestinian prisoners. If they did agree, everyone would be able to return safely to their families. Doesn’t that sound more worth fighting for than war?

There is a single story, promoted by Netanyahu, that Israel must fight until it has destroyed Hamas.

There is another story. Maoz Inon’s parents were both murdered by Hamas on October 7th. As soon as he had finished sitting shiva, he took up his call for peace. All he wanted was an end to the war.

Speaking to American news this week, he said: “A military invasion into Gaza will just make things worse, will just keep this cycle of blood, the cycle of death, the cycle of violence that’s been going for a century.”

His call for peace is echoed by other families of those who lost loved ones on October 7th. They have lobbied, produced videos, and sent letters to Netanyahu, begging to be heard.

Some are desperate for the government to recognise that further death is not what they want. Now, as Netanyahu has killed more than 20,000 Palestinians, their call has still not been heard.

And after all those dead, is Hamas any closer to being destroyed? Of course not. All this bombing does is ensure that a new generation of Palestinians trapped in Gaza will grow up to hate Israel.

This war is how you get more terrorists. It’s how you ensure that war never ends. Wouldn’t it be better to fight for a ceasefire than to fight for a war?

There is a single story that the nation is united in war.

There is another story. This week, 18-year-old Tal Mitnik was sent to military prison in Israel for refusing to fight in the war. Although this news has barely made it into English-language media, many Israelis have expressed their support.

Writing to Haaretz, one refusenik wrote: “I was inside. We were so brainwashed there. I refused and I’m not the only one. I have a family and this is not a war with a clear purpose. […] My children will have a father and I hope yours will too.” Another parent wrote: “My son is also refusing. I will not sacrifice him for Bibi.”

There is another story: that this is Netanyahu’s war, not ours.

There is another story: that war is not the answer.

There is another story: that every captive must go free.

There is another story: that all bombs and rockets must end.

There is another story: that we will not give licence to any more bloodshed.

There is a story that the nation is at war. In times of war, the government must tell that as the only story, to blot out alternative stories, to ensure that war is the only way.

But there are other stories. And, if we tell those other stories, there will be other ways.

Shabbat shalom.