One day, word came to Joseph, “Your father is failing rapidly.” So Joseph went to visit his father, and he took with him his two sons, Manasseh and Ephraim.

When Joseph arrived, Jacob was told, “Your son Joseph has come to see you.” So Jacob gathered his strength and sat up in his bed.

Jacob was half blind because of his age and could hardly see. So Joseph brought the boys close to him, and Jacob kissed and embraced them. Then Jacob said to Joseph, “I never thought I would see your face again, but now God has let me see your children, too!”

He drew them close, so close, and kissed their foreheads, then offered his blessing, his last testimony upon his grandchildren. He placed his hands on his grandchildren’s heads and said:

“The whole world hates us! They’ve always hated us, right from Pharaoh until today. They’ll never accept us, because they’re jealous of us. They can’t stop thinking about us, even though we’re a tiny fraction of the world. Well, good! We’re going to keep being Jewish to spite them. That’s it, boys, be Jewish to wind up the antisemites. As long as they hate us, wear your yarmulkes.”

Of course, this is not what Jacob said to his grandchildren.

What would have happened to Jews and Judaism if this was all Jacob had to pass on?

Ephraim and Mannasheh would have nothing on which to base their identities but a negative. They would see themselves as Jews only by victim of circumstance. Their choices would be to reluctantly accept their Jewish status as a miserable burden from previous generations; or to concoct a paranoid worldview that lashed out at everyone; or to ditch being Jewish as soon as they got the chance.

Jacob would just have left the boys a neurotic mess, with no pride in themselves or joy in their lives.

Jacob would not have said this to his children, but what are we teaching to ours? Are we teaching them to love being Jewish, with all its culture, rituals, festivals, beliefs, and ways of building community? Are we showing them how to love themselves and their heritage so that they can delight in it for many generations?

Or, are we imparting a negative identity based on misery and fear?

If you open up some of our communal newspapers or listen to some of our representative bodies, it is very much the latter. Maybe it is not as vulgar as the parody I just made up for Jacob, but it comes through in how they talk, and what stories they choose to tell.

It is as if, for them, Jews only exist because of antisemites, and our Jewishness is only exerted when defending ourselves against antisemitism.

This idea is not new.

In 1944, as the war came to an end, French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre was trying to understand antisemitism. He wrote “Portrait of an Antisemite,” in which he looked to his contemporary antisemitism in France. Sartre saw antisemitism as a lie to uphold class distinctions. The rich relied on antisemitism because it gave them an excuse to put the blame for inequality and injustice somewhere else. The poor turned to antisemitism because, by creating outsiders, it gave them a feeling of belonging to a nation in which they really had no portion.

Antisemites, he said, were people who couldn’t face their own reality, and absconded from their own freedom, to project their fears onto Jews, both real and imagined. From this, he coined the famous saying that “if Jews didn’t exist, antisemites would invent them.”

This was a useful way to begin to understand antisemitism – as a fear constructed about Jews, but in spite of what any Jews were actually like.

Sartre then goes on to ask a question: “does the Jew exist?” That is, if antisemites are just angry at imaginary Jews, what does that make of real Jews? Sartre concludes that Jews do exist, because of their shared experience of antisemitism. Jews exist in response to the persecution they face. Quite literally, he says, “the antisemite creates the Jew.”

The Jews themselves, he said, were outside of history, but victims of its oppression. If antisemitism were to disappear, then, so, too, would Jews. If only everyone were to throw off the shackles of class society, the Revolution would resolve the contradictions that antisemitism needed, and Jews would be able to assimilate into a newly-ordered utopia. Then, they could give up being Jews, and finally become citizens of their countries.

What he outlines is really a popular Bolshevik understanding of antisemitism, sprinkled with existentialism. For many opponents of antisemitism, its appeal was that it could suggest a way out of hatred and racism.

But, for those of who are Jews, that’s not helpful at all. If being liberated as people means being destroyed as Jews, why would we want such a thing?

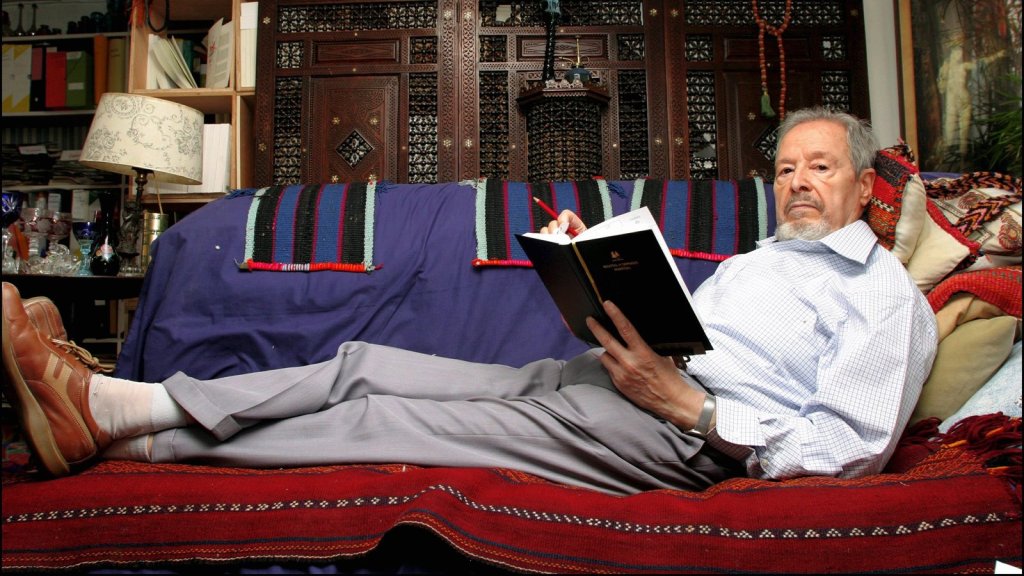

Sartre had a friend, interlocutor, and fellow intellectual, in Albert Memmi. Like Sartre, he was a French-inflected socialist. But, unlike Sartre, Memmi was a Jew. Born in Tunisia in 1920 to a poor Jewish family, Memmi became a leading thinker, and a revolutionary in Tunisia’s war for independence. Sartre admired Memmi, and brought his anticolonial writings to a European audience.

In response, Memmi wrote “Portrait of a Jew,” and its follow-up, “The Liberation of the Jew.” Memmi was able to describe first-hand experiences of antisemitism on two continents. His personal struggles with prejudice elucidated very clearly why Jews would not want to assimilate into Christian France, even in the classless society Sartre imagined. Centuries of racism and religious discrimination showed him that neither Christianity nor Frenchness offered much hope for Jewish emancipation.

More interestingly, Memmi decided to answer for himself the question, “does the Jew exist?” For Memmi, the answer was a resounding “yes.” Jews exist, and, contra Sartre, have our own history, culture, and civilisation. Yes, that has been created in response to antisemitism, but also in spite of it. Jews were constantly creating our own culture.

Jewishness, said Memmi, was what Jews decided to create in each generation, and could be constantly remade, as part of Jews’ engagement with their own heritage. For Memmi, if antisemitism did not exist, Jews still would. Even if, as many Bolsheviks imagined, the world could be freed of superstitious religion, the Jewish national culture would carry on, and thrive in new ways.

So, antisemitism may create the Jewish condition, but it was the Jews who created Jewishness. We were the authors of our history.

After the service, we will hear from Rachel Shabi, as she talks to us about antisemitism and its challenges. Her thoughts are prescient, and we should pay close attention to them. We need to understand antisemitism, where it comes from, and how to combat it.

Yet we must remember that studying antisemitism can only tell us about antisemites. It cannot teach us about Jews.

Jews make Jews. We decide who we are. Through our love of our heritage and community, we build up Judaism, and we make it what it should be.

So, when we talk to the younger people in our communities, we cannot let their identities be formed by fear of antisemitism.

We must tell them why we have chosen to keep on being Jewish, and give them good reasons to keep it up too. Whether raised Jewish, converted, or affirmed, all of us have chosen being Jewish, and for good reasons that are bound up in love, not defined by hate.

Tell them about your favourite recipes and the best of Jewish songs. Show them Jewish art and take them to Jewish plays. Celebrate the festivals with them because you truly want to bring them to life. Mourn and fast with them because it is filled with meaning.

Teach them that God has given us a sacred task on earth; that we exist in this world to perfect it. That everything we do can light up divine sparks. That we are called upon to unify all that exists with its Creator.

Bless them with the words that Jacob actually spoke, and say:

“May the God before whom my grandfather Abraham and my father, Isaac, walked—

the God who has been my shepherd all my life, to this very day, the Angel who has redeemed me from all harm. May the Eternal One bless these children. May they preserve my name and the names of Abraham and Isaac. And may their descendants multiply greatly throughout the earth.”