After our wedding, everyone was excitedly sharing photos and videos. Laurence pored over them and made albums.

I liked them, but the pictures felt a bit flat. What I was craving was words.

I wanted to re-read everything everyone had said. I went about collecting the speeches people had given, and recounted them again. On honeymoon, Laurence and I re-read our vows to each other, this time pausing and discussing them.

I discovered anew how much more I loved words than pictures or videos. Pictures are static. Even videos, because they only caption one moment from one perspective, feel too final.

To me, words feel so much more alive. Stories are such a great way to engage with events and ideas, because they can be retold so many times and in different ways.

Isn’t this, after all, what religion is: storytelling to access something sublime and unfathomable; a collaboration by people sharing their best narratives and ideas?

We have inherited a literary tradition, our Torah, which is an exercise in storytelling: a process of openly wondering at the world through poetic sagas and emotion-filled songs.

For some, however, these stories fall flat. They see the words the way that I see pictures.

Fundamentalists will look at our story of a donkey talking to a prophet about an angel and think: that must be the historical truth of what happened.

Similarly, the New Atheists look at this beautiful poetic piece about the prophet Balaam and think: how stupid must religious people be to believe this nonsense?

This is not just a misunderstanding of Scripture. It’s a misunderstanding of storytelling itself.

Seemingly, it does not occur to them that this might be an invitation into conversation. They can’t comprehend that this might be a poem, crying out to be read aloud, sung, chanted, interpreted, and retold to make sense of all the wonders of the world.

Perhaps these talking animals and sword-wielding celestial beings aren’t part of history textbooks but reveal a different kind of truth altogether.

In Britain, we are mercifully spared from most of these types of fundamentalist reading. We don’t have to deal with as many evangelical Christians as our American cousins do.

But we have our own local brand of biblical literalists. They are the radical atheists who have got to know our sacred texts solely for the purpose of showing how irrational they are. The most famous of them is Professor Francesca Stavrakopoulou, a biblical scholar at the University of Exeter.

In 2021, Stavrakopoulou brought out her most recent work, God: An Anatomy. The book’s objective is to show that the God of the Bible was an embodied being. He was a gargantuan man with a big beard who sat on his throne in the Jerusalem Temple, gobbling up the sacrifices priests burned for Him.

The God of the Bible, Stavrakopoulou argues, was just like any other ancient god: basically a massive person with all the associated wants and desires. She collapses about 4,000 years of history and three continents into one culture and seeks to show that the biblical god was just like all the others.

And, like all the others, the biblical god had a body.

Sometimes, her evidence for this scant. There are entire pages dedicated to making quite wild claims about the biblical god, appended with just one footnote that points to an obscure translation of a verse from the Psalms.

But, overall, there is plenty of material to go off. If you open up any page of Tanach, you will probably find God described in anthropomorphic terms.

Take our haftarah.

This week’s reading comes from the book of Habakkuk, a 6th Century BCE Prophet in Judah. The book is a vivid war fantasy, where the prophet describes the Judahites crushing the invading armies, some time in the mythic past, and hopes that it will happen again.

Throughout the text, God comes alive as a warrior. He (and I’m going to use the masculine pronoun advisedly here) is an embodied fighter on behalf of the people.

God’s hand lights up with radiance; God’s feet trample over mountains; God’s piercing eyes make the nations trembled with fear.

God has all the equipment of an ancient military commander. He rides in on a chariot with His horses and shoots out arrows from His archer’s bow. God rips the spear from the opposing general’s arm and stabs it into his head.

How are we supposed to read this?

Well, for a biblical literalist, you have to take it at face value. That’s exactly what Stavrakopoulou does. She makes the case that this was precisely how the ancient biblical authors and audience understood their god.

Their god was a big bloke with some massive weapons and blood lust.

Stavrakopoulou draws on other ancient gods, whose worshippers also describe them in embodied terms. The Canaanite high god El also had radiant arms. The Akkadian god Enki also trampled over mountains. The Assyrian god Ashur also fought with a bow.

The Israelites, then, were just riffing on old themes. Like the Pagans around them, they were silly enough to believe in all that religious nonsense of big beings. The biblical god was no different to Zeus or Jupiter.

Overall, reading Stavrakopoulou, you get the impression of someone listening to a concerto who can identify every note from every instrument but cannot hear the music. Her entire objective is to show that the tune isn’t even that good because other songs have been written before.

All the way through, it seems like a strange motivation for going to all the effort of learning Scripture and Ancient Near Eastern texts. Then, we get to the final chapter, entitled “Autopsy,” and we understand her true objectives.

She concludes: “the God of the Bible looks nothing like the deity disected and dismissed by modern atheism. […] Their dead deity is a post-biblical hybrid being, a disembodied, science-free Artificial Intelligence, assembled over two thousand years from selected scraps of ancient Jewish mysticism, Greek philosophy, Christian doctrine, Protestant iconoclasm and European colonialism. In the contemporary age, this composite being has become a god who forgot to create dinosaurs and failed to account for evolution; a god who allows cancer to kill children but hates abortion…”

Stavrakopoulou despises religious belief. So, if she can demonstrate that the biblical god was just like the Egyptian pantheon, and that this embodied god could be killed, then she can also strip the modern god of His powers and kill Him too.

This is the worst of Enlightenment hubris. 19th-century anti-religionists imagined that all religion was just silly superstition, which would eventually be washed away by the cold science of reason.

Our movement, like all progressive religions, has consistently argued for an alternative approach. We see all of history as an evolving effort to understand the sacred mystery beyond our comprehension.

It almost certainly is true that, before Ezra led the exiles back from Babylonian captivity in the 4th Century BCE, most Israelites did worship a small pantheon of Canaanite deities. The Prophets from before this time regularly condemn them for it.

But, while they may have been idolaters, they were not idiots.

If you told one of them that you’d just seen the fertility goddess Asherah out for a stroll in the marketplace, or that the storm god Baal came to your house this morning for a cup of tea, they would think something was wrong with you.

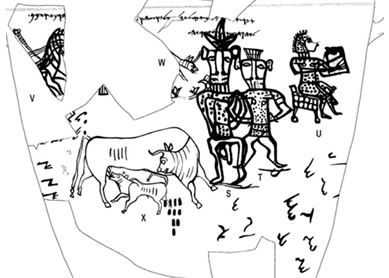

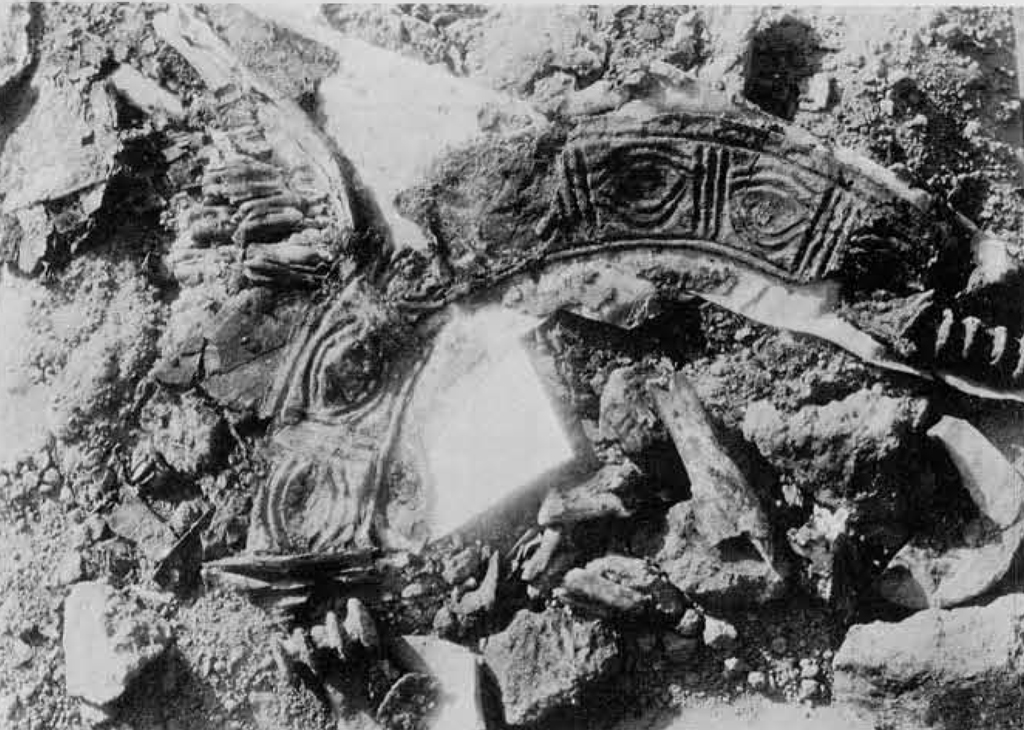

Another scholar of ancient religion, Iraqi Assyriologist Zainab Bahrani, helps us make sense of the ancient worldview. For the Mesopotamians, images were not reproductions of originals like portraits and photographs are for us today.

Instead, they saw their icons as ways of writing existence into being. They were in an active process with their gods of creating reality.

In matters of religion, literal interpretations are dead-ends. Words like metaphor don’t do it justice. Symbols like clay deities stand in for whole cosmologies. They are ways that human beings have tried to understand something that, by definition, is beyond our comprehension.

Perhaps most importantly, Stavrakopoulou misses what a massive departure it was that ancient Israelites abandoned all images in favour of a predominantly literary culture.

In a society where you cannot depict God, but can only engage in description and storytelling, you have to be more imaginative when you try to make sense of infinity.

Poems, sagas, and speeches, like those from our Tanach, are never fixed in their meaning. They are openings that invite listeners to think with them, talk back to them, and struggle for deeper understandings.

When someone reads a text too literally, they strip it of its vitality. Atheists and fundamentalists, both literalists of different kinds, strip the soul from the search for divine truth.

Tell stories, make poems, create art, look for that great truth beyond our reach… and don’t take any of it too seriously.