In Judaism, night comes before day. The day begins when the sun sets and the first stars appear in the sky.

This has been the way of the world since its mythic origins.

In the beginning, there was endless darkness. Then God said “let there be light.” And there was light.

And God separated the light from the darkness. The first distinction. And the darkness God called night, and the brightness God called day.

And there was evening, and there was morning. A first day.

Having created nights and days, God populated them with matter. At the end of each period of creation, there was evening, then there was morning. Each day.

During the sixth day, God created human beings and placed them in a garden. Then there was evening.

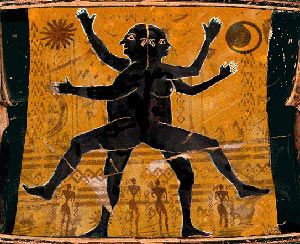

The first human beings had never seen an evening before. They did not know that the sun could set. They did not know the difference between night and day.

What must it have been like for the first sentient beings to realise who they were and who their Creator was, only to see the sun disappear? How frightened they must have been!

Perhaps they called out to God and asked for guidance. But that evening marked the beginning of the seventh day, and God was resting. God did not answer them.

Our Talmud teaches that when the first human beings saw their first nightfall, they fell into despair. Adam feared that the sun had disappeared as punishment for his sin. He worried that the world would now return to the endless darkness with which it began.

Eve cried. She fasted and prayed. Adam and Eve wrapped their arms around each other and held their bodies close as they prepared for the end.

Then the dawn broke.

And they realised: this is the way of the world.

The world began in autumn, at the festival of Rosh Hashanah.

When the first winter nights crept in, and they saw the length of days decreasing, they panicked once more. Now in exile from Eden, they had no way of knowing what would come next.

Again, they fasted, wept, and prayed.

Then the spring came, and brought with it longer days.

And they realised: this is the way of the world.

We begin with darkness. Light follows.

There is evening. Then the dawn comes.

There is winter. And it always becomes spring.

This is the way of the world.

We can observe this dialectic in almost all matters of life. Our suffering is followed by joy. Our struggles are replaced by triumphs.

Some days feel like endless nights, but the dawn is always waiting for those who are patient for it. So we hold each other close and wait for the sun to rise.

This is the way of the world.

These trends appear, too, in history. There will be periods of decline followed by ages of plenty. There will be economic busts, and there will be booms. There will be war, but peace will come.

This is the way of the world.

But human history is different from all other natural rules. The order of night and day and the structure of the seasons was predetermined before we arrived on this earth.

History, on the other hand, is made by human beings. History is the one area of life where we can, collectively, choose what happens. Our actions determine whether we live in the winter of war or bountiful springtime.

So, it is incumbent upon us not just to hold each other and wait for morning, but to drag the sun over the horizon and demand that day appears.

In 1969, “Shir LaShalom,” became the anthem of the Israeli peace movement. In the final stanza of the song, we sing out: “Do not say the day will come. Bring on the day.”

Just as people make the active decision to go to war, peace is also a choice. Those who want an end to war cannot just wait in the darkness.

We sang Shir LaShalom in this sanctuary on Simchat Torah. I felt, and I think many of you did too, truly jubilant at the news of ceasefire and hostage release. After two years, we could finally see a possible end to the suffering.

My jubilation was tinged with pain as I remembered the last time that Shir LaShalom was chanted throughout synagogues.

That was in 1995. Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat had shaken hands on the lawn of the White House. They had agreed to the Oslo Accords.

While already imperfect and tentative, the Oslo Accords of three decades ago were the last major effort at a comprehensive peace deal between the Israelis and Palestinians. They paved the way for mutual recognition and the possibility of two states.

High on the dream of peace, Rabin joined Peace Now protesters in Tel Aviv Square and sang along to Shir LaShalom. With the lyrics still in his breast pocket, Rabin headed to the car park. There, a far right fundamentalist waited for the Prime Minister, and shot him dead.

There is still a copy of Shir LaShalom, stained with Rabin’s blood. There are those words, covered in the blood of a man who tried to make peace: do not say the day will come, bring on the day.

Yes, we must indeed bring on the day. But there are some who want to return us to endless night.

An Israeli fanatic shot dead Rabin to stop his day from dawning.

When Hamas saw the prospect of the Oslo Accords creating two states, they launched suicide bombing attacks on public transport. They took control of Gaza and promised endless war.

The Israeli far right wrested control over the offices of government. They promised there would be no Palestinian state and that every effort to achieve one would be swiftly repressed.

It saddens me that, even in the brief interludes since Rabin’s assassination when Netanyahu’s party has not had control over the legislature, few Israeli politicians have attempted to break from their logic of violence and occupation as the only answer to the Palestinian national question.

Daybreak always comes, but there are those who prolong the darkness, and we have been living through a terribly long night. The call to bring on the day from earlier generations has been eclipsed by militarism and fear.

We have endless war. This is the way of the world.

But this is the way of the world as some have chosen to make it. And we can make the world another way.

On Monday, we saw the first thing in a long while that looked like a sun beam.

We celebrated the hostages coming home and an end to the bombing of Gaza. It was the first reminder we have had in a long time that peace is possible, and war is a choice.

We are able to bring on the day.

Now we must create even more sunshine.

But we have become so accustomed to darkness that the dawn may even be painful.

In daylight, we will have to look hard at the choices that made this war so prolonged and destructive. We will likely see that peace was possible much earlier and that more hostages might have come back alive sooner. We may ask searching questions about the morality of this war.

In the light of day, we will have to look hard at what Israel has become, and what the spiritual state of our Jewish institutions now is.

But we must bring on the day. We cannot return to the long-lasting night of war, murder, zealotry, and extremism. We cannot let anything that happened in the last two years ever happen again.

Throughout this dark night, our Progressive Jewish counterparts in the Israeli Reform Movement have been pushing hard for serious change.

They have been protesting outside Netanyahu’s house every Saturday evening. They have been joining Palestinian olive farmers in the West Bank to protect them from settlers. They have been demanding a real overhaul of the deep, structural causes of this century-long conflict.

My month with Rabbis for Human Rights before I began here helped positively frame my rabbinate. Although the picture on the ground is bleak, it made me realise just how many people are desperately trying to create daylight in the darkest contexts.

I hope that we will not fall into complacency now because the hostages are home. The task of peace building is more pressing than ever.

I want us to draw ever closer to those who are defending human rights and trying to bring about a future based on dignity and equality. I hope that, next year, we can bring a full delegation of Progressive Jews to support the West Bank olive harvest. I hope this can be a moment where we truly embrace the cause of peace.

This is not the seventh evening of creation. It is not the time to rest. We cannot leave our colleagues alone in this struggle now.

This is the first dawn of a new morning.

It is an opportunity for real accountability. It is a chance for meaningful peace building. It is the first crack of sunshine, and we have to drag out every possible ray of light to join it.

We must wrest the light into the darkness.

We cannot say the day will come.

We must bring on the day.