“How many more signs do you need that God is not there?”

This was the question one congregant asked last week when I went round for a cup of tea. In fact, a few of you have asked similar things recently.

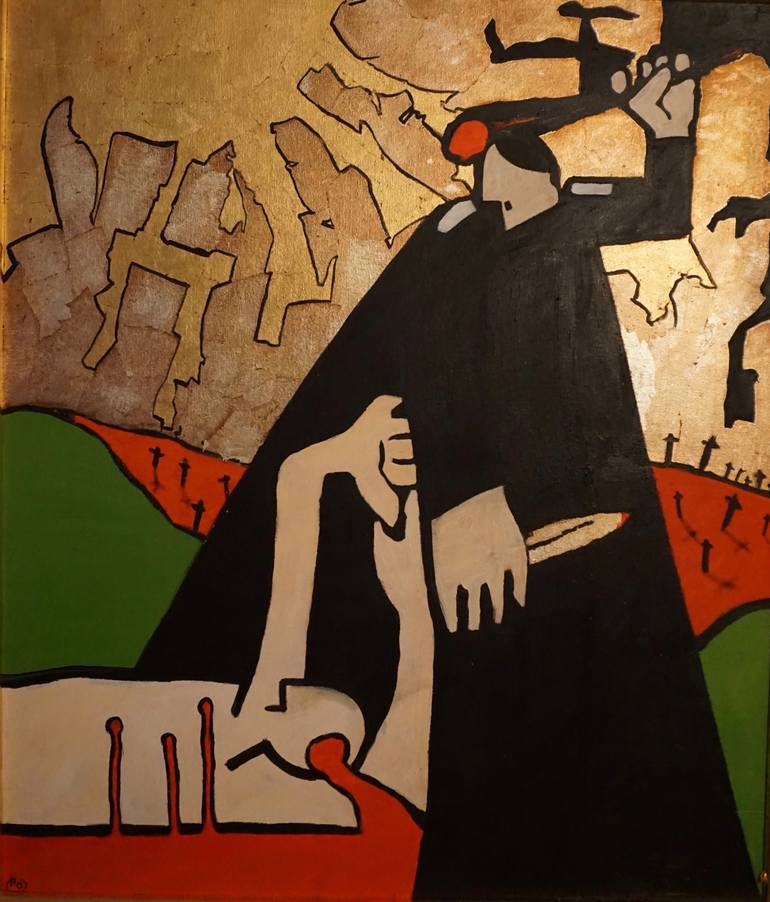

None of you was asking out of arrogance or triviality, but expressing a real despair at the state of the world. The ongoing war, which has claimed far too many lives, is enough to incite a crisis of faith in even the most devout believers.

Why will God not just stop the war? It is a serious question, and one that deserves a serious answer.

How desperate are we all to see a ceasefire, to see Gaza rebuilt, to see the hostages returned home, to know that the Israelis will no longer hide in bomb shelters, to know that no more people will be rushed to hospitals, to see an end to all the violence and bloodshed?

And it goes deeper than that. How much do we all wish that none of this had ever happened; that there was no war for us to wish to end?

In our anguish at the cruelty, we cry out to the Heavens. There is no answer from On High, so we wonder if there is Anyone there listening at all.

I will not be so presumptuous as to imagine I have the answers. I do not know the nature of God and can give no convincing proof of how our Creator lives in this world. In fact, if I found anyone who thought they did, I would consider them a charlatan.

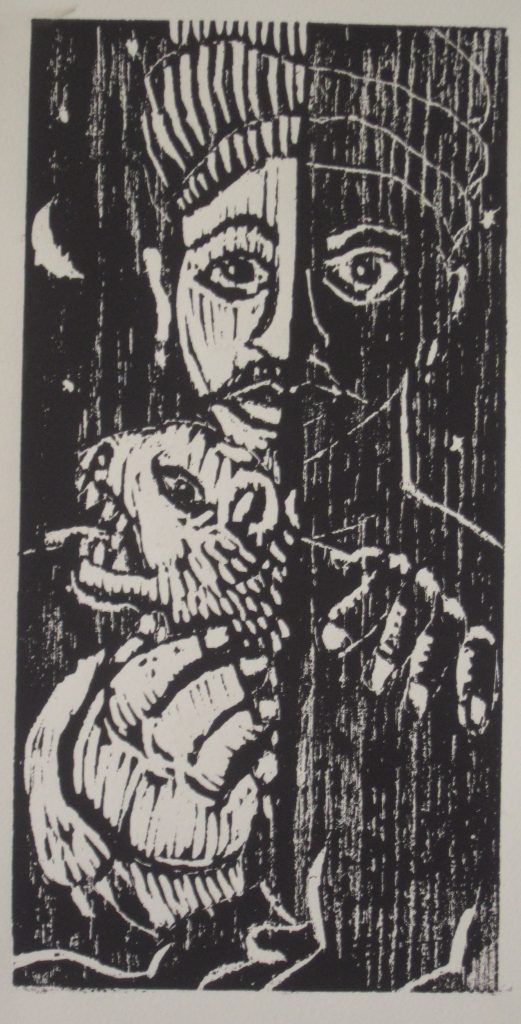

The great 15th Century Sephardi rabbi, Yosef Albo, said: “If I knew God, I would be God.” We are, all of us, animals scrambling in the dark, as we try to make sense of the mystery.

But we come to synagogue so that we can scramble in the dark together, feeling that if we unpick the mystery in community, we will get further, and develop better ideas. Allow me, then, to share some of my own thinking, so that we can be in that conversation together.

How many more signs do you need that God is not there?

In our Torah, there were times when God did indeed show signs of presence. In the early chapters of Genesis, God walks through the Garden of Eden in the cool of day. At the exodus from Egypt, God came with signs and wonders and an outstretched arm. As the Israelites wandered in the desert, God appeared as a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night.

This is the kind of sign that we might want from God now, then.

At a hostel in Jerusalem, I met an evangelical Christian who was absolutely convinced that everything happening in the Middle East was already foretold by the Bible and that God was about to rain down hell on the Palestinians and then all the Jews would finally accept Jesus.

Suffice to say I do not think such a God would be worthy of worship.

And I highly doubt this is the kind of divine intervention any of us would embrace.

Is there an alternative way we could wish for a sign?

Some great indication that Someone greater than us is involved in the story and cares about human suffering. Perhaps just a gentle hand to reassure us everything will be OK.

Deep down, most of us know that no such sign will come.

God did, however, send another sign in the Torah. A sign, perhaps, not to look for signs. A sign that God was not going to get involved, no matter how desperate it all seemed.

The rainbow.

At the start of the story of Noah, the world was filled with violence. Everyone had turned to war – nation against nation – all against all. The entire planet was rife with destruction.

God slammed down on the reset button. God sent a flood so catastrophic that it killed everyone bar one family. The flood was like a thorough system cleanse, designed to strip the earth back to its original state and allow Noah to rebuild.

Then, as soon as the rains had stopped and the land had returned, God looked at the devastation, and swore: “never again.”

God promised Noah: “I will maintain My covenant with you: never again shall all flesh be cut off by the waters of a flood, and never again shall there be a flood to destroy the earth.”

God hung a rainbow in the sky, and told Noah it was a symbol that there would be no more divine interventions:

“When I bring clouds over the earth, and the bow appears in the clouds, I will remember My covenant between Me and you and every living creature among all flesh, so that the waters shall never again become a flood to destroy all flesh.”

The rainbow, then, is a sign that God is there, and a sign that God will not get involved. Even if humanity goes back to being as violent as it was in the Generation of the Flood, God is not going to step in and destroy as at the start.

If the rainbow is a sign that God will not come and strike people down when the world is in crisis, it is also a sign of the other half of the covenant. Human beings must now be God’s hands on earth. We have to be the ones to do what we wish God would.

For Jews in the rabbinic period, every rainbow was a reminder to them that God would not act, so they had to take the initiative. They would look up at the sky and say “blessed is God, who remembers the covenant.”

According to the Jerusalem Talmud, no rainbow was seen during the entire lifetime of Rabbi Shimeon bar Yochai. He was so righteous and brought so many others to do good deeds that there was no need to be reminded any more of the covenant. Bar Yochai was one who acted so much like he was God’s actor on earth that even God did not need to send reminders.

The idea that human beings had to be God’s hands became even more important in the post-Holocaust world. Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits escaped from Germany in 1939 and went on to become one of the leading Orthodox rabbis of the 20th Century. For him, a traditional religious Jew, grappling with the enormity of the Shoah, he had to find a way to deal with God’s seeming absence at Auschwitz.

So, Rabbi Berkovits said, the problem lay not with God’s inaction, but with humanity’s. In his book, Faith After the Holocaust, Berkovits wrote:

“Since history is man’s responsibility, one would, in fact, expect [God] to hide, to be silent, while man is going about his God-given task. Responsibility requires freedom, but God’s convincing presence would undermine the freedom of human decision. God hides in human responsibility and human freedom.”

What Berkovits is saying is that it might be in God’s nature to prevent catastrophe, but it would undermine human nature if God did. In order that people can realise our freedom and our full potential, God has to stand back.

It seems that, in almost every generation, Jews are asking why God does not intervene to stop violence.

In each generation, we find an answer: God does not intervene, because that’s our job.

It’s not that any of these classical sources doubt God’s existence or question God’s presence. They just don’t think it is God’s responsibility to act. It is ours.

There is no flood coming to wipe out war or lightning bolt coming from the sky to strike down the wrongdoers.

We began with a question.

How many more signs do you need that God is not there?

Perhaps we can now reframe it positively.

How many more signs do you need that you must act?

God is not going to stop war. So we have to do our bit to bring it to an end.

Even in our small corner of the world, we have to do all we can to push for peace and justice.

So, on the days when you find yourself looking for the sign, you be the sign.

You need to be the sign to somebody else that there is hope in this world.

You need to be the sign that peace is possible.

You need to be the rainbow.

Shabbat shalom.