We must build a wall to protect you from the Moabites.

We must build a wall. You cannot trust the Moabites.

The Moabites are on the other side of the salty Dead Sea and the Jordan River. A river is not big enough to keep the Moabites away from our land. They will take everything we have if they get the chance.

The Moabites are dangerous and brutal. They will destroy you if they get the chance.

We must destroy the Moabites before they can destroy us. We must kill their kings. Their king Eglon is a murderous tyrant. You will never be safe as long as he reigns. You must kill him.

You must kill every Moabite that stands in your way. You must capture the Moabite city of Heshbon. We need it to keep the Moabites away from us.

We must build a wall to protect you from the Moabites.

They must never come near you.

You must never meet them.

Because, if you met the Moabites, you might see that they are not monsters. You might see that they are like you.

And then you would not be able to kill them.

And then you would ask why we are building walls.

And then you would ask who was building these walls.

So you must always abhor the Moabites. You must fear them and revile them.

We must build a wall to protect you from the Moabites.

It must be high enough to protect you from them. It must be high enough to protect you from yourselves. It must be high enough to protect you from peace.

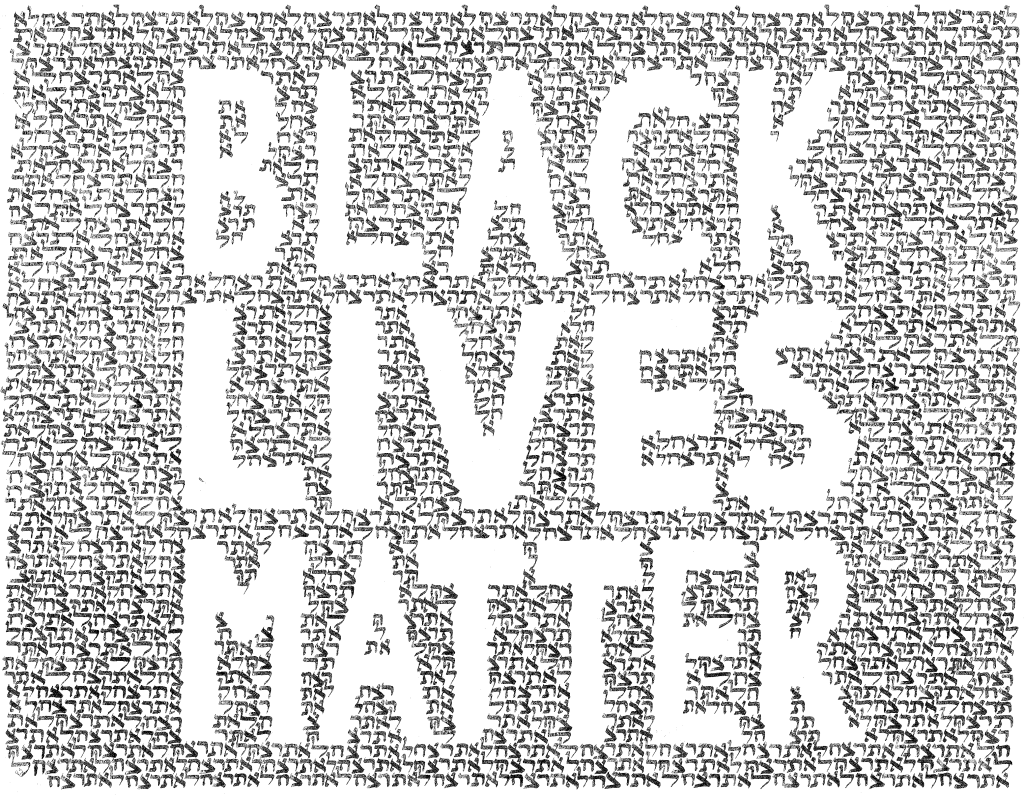

You may not immediately notice it, but nestled in this week’s Torah portion is an early example of war propaganda. In the vulgar and violent story of Lot is an origin myth for the Israelites’ greatest enemy: the Moabites.

The scene begins as God destroys Sodom and Gamorrah, two cities so wicked and licentious that they have to be wiped out and turned into the Dead Sea.

Only Lot and his daughters escape from that awful place. They retreat into the mountains on the east of the Jordan. There, the two daughters get Lot drunk, seduce him, and use him to sire their children.

The oldest is called Moab. And to really drive the point home, the Torah adds explicitly: the father of the Moabites.

The women in this story are not even given names. They are just grotesque plot devices to tell us how awful the Moabites are.

Those people, Israel’s nearest neighbours to the east, are so wicked that they came from Sodom. Their ancestors are so twisted that they were born of incest, drunkenness, and assault. It is a story to inspire revulsion in its Israelite listeners.

This is part of a general campaign of literary warfare against the Moabites, continued throughout the Torah.

Isaiah promises that the Moabites will be trampled like straw in a dung pit. Ezekiel vows endless aggression and possession. Amos says the whole of Moab must be burned down. Zephaniah swears that Moab will end up just like Sodom, a place of weeds and salt pits, a wasteland forever.

The war propaganda reflects real wars. The ancient Israelites did repeatedly wage war, conquer, and capture Moabites. They did kill their kings, and they did turn Moab into a vassal state.

Based on the Moabites’ texts, we can see that it also went the other way, and that Moab also captured, conquered and slaughtered Israel.

We do not know how many Israelites or Moabites died in these wars. We do not know how many people grieved their families and homes. All that remains is the propaganda of the competing tribes.

Today, it is hard to imagine why anyone would have hated the Moabites so much, or even that we would believe the hyped-up stories of how vulgar they were. With centuries of hindsight, we can see that they were probably very similar to the Israelites, but dragged into wars for the glory and material wealth of their kings.

Of course, there were dissenting voices at the time. The Book of Ruth can be read as a polemic about love between Israelites and Moabites. It is a beautifully humanising story where the central character, Ruth, is portrayed as a Moabite who is kind, loving, devoted to her family, and committed to Israelites.

As long as there has been war propaganda, there has been anti-war propaganda, and our Torah contains it all.

This Shabbat, we honour Remembrance Day. We think of all of those who died in wars past, and those who served their countries in military operations. This feels so close to our hearts, as we reflect on the great toll wars took on military personnel and their families, including many in our communities.

We remember the pain of those who have lived through and died in the awful wars that have passed.

This solemn day dates back to the armistice of the First World War, on November 11th 1918. The following year, England hosted France for a shared banquet as they recalled the ceasefire. From then on, it became an annual day of reflection on the horrors and sacrifices of war.

During the First World War itself, even as the conflict was ongoing, many challenged the war. The great British-Jewish soldier-poet, Siegfried Sassoon, charged that the war had been whipped up by jingoistic propaganda.

In July 1917, Sassoon published “A Soldier’s Declaration,” which denounced the politicians who were waging and prolonging the war with no regard for its human impact.

Sassoon lambasted “the callous complacence with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share, and which they have not sufficient imagination to realise.”

It is true that people like me, who enjoy peace, cannot even contemplate the pain that people went through in fighting wars and enduring bombing.

Today, we honour them.

Honouring them does not mean parroting propaganda and whipping up war.

Quite on the contrary. It is the duty of every civilian to ensure as few people as possible ever have to fight in wars. It is our responsibility to minimise the number of people who suffer and die in armed conflicts. It is our task to pursue peace.

We, who will never know the sacrifices of the front line, must heed Sassoon’s call, and resist the drive to war.

So instead:

We must tear down every wall with the Moabites.

Yes, with the Moabites, and, yes, with the Germans, the Russians, the Chinese, the Koreans and the Iranians.

We must find commonalities and engage in shared struggles.

We must learn to trust our fellow human beings and distrust the propaganda of war.

We must cease all killing. The machinery of war has destroyed too much and taken too many lives. We must endeavour to put an end to violence and destruction.

We must learn to understand the people we are told are our enemies.

We must tear down every wall.

Shabbat shalom.