His disciples were dismayed. “Where are you going?” they asked.

“To blot out the name of Amalek!” he replied.

The students were anxious. They shuffled in their seats. They knew who Amalek was. They knew what the injunction to blot out Amalek’s name meant.

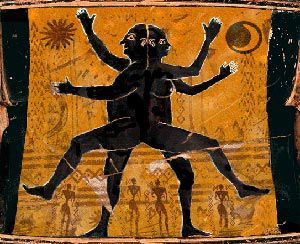

When the Israelites were wandering in the desert, the Amalekites attacked them from behind, targeting the weakest members; the old, the ill and the tired. The book of Deuteronomy adjured them: “blot out the memory of Amalek from under Heaven. Never forget.”[1] This call in the Torah spoke to far more than historic memory. It was a call to violent revenge. Surely this couldn’t be what the rebbe meant?

One of the rebbe’s students stood up. “Rebbe, you can’t be serious?”

“Of course I’m serious,” said the rebbe. “It’s Purim.”

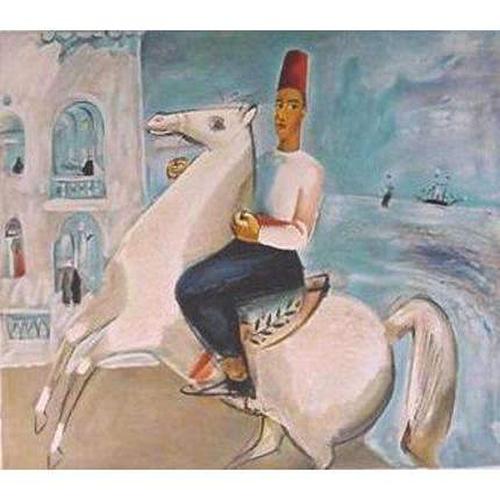

Purim? Purim, of course. It was the time to read the story of Esther. Haman, the wicked adversary of the Jews in the story of Esther, was an Amalekite. Haman was a descendant of Agag, the king of Amalek. Haman had plotted to kill the Jews in their entirety. As they read the Megillah, at every mention of his name in the scroll, the disciples had been booing to drown out the word. By the end of the story, Haman’s fortunes have been completely overturned. The king decrees that, instead of Haman being able to kill all the Jews, the Jews can kill all of Haman’s supporters and descendants. They go on a fortnight-long massacre, killing 75,000 people.[2]

This has always been interpreted as part of the act of blotting out the name of Amalek. Surely this couldn’t be what the rebbe meant? Surely he didn’t think that violence and genocidal rampaging had any place in Judaism? It was a bawdy story, not an instruction manual. What could the rebbe be thinking? The students followed him out into the streets, rushing after him as he pattered away down the cobbled path.

One of his students caught up with the rebbe, panting, saying: “Sir, with the greatest respect, I think you may be mistaken. Our Talmud teaches us that we no longer know who the nations are. Empires and diasporas have scattered us. Nobody knows their lineage. We cannot possibly know who the Amalekites are any more.”[3]

The rebbe was undeterred. “You do not need to know somebody’s ancestry to know who Amalek is,” he said, as he carried on walking. “We know our enemy.”

Another student shot up and interjected. “Sir, with the greatest respect, I think you may be mistaken. Our commentators argue that the duty to blot out Amalek is upon God. The Torah says that Amalek should be blotted out from under Heaven. That is, it is Heaven that will destroy Amalek, not us.”[4]

“Nonsense,” said the rebbe. “Judaism calls us to action. We cannot wait for God to solve our problems. We must go and address them now.”

He marched on, now with the whole village trailing behind him. Everybody was agitated, determined to keep him from doing something foolish.

Another student challenged the rabbi. “Sir, with the greatest respect, I think you may be mistaken. Nahmanides teaches that we cannot attack Amalek out of a sense of revenge, but only out of a sense of the honour of God. If you seek destruction now, you will be violating this mitzvah, not honouring it…”

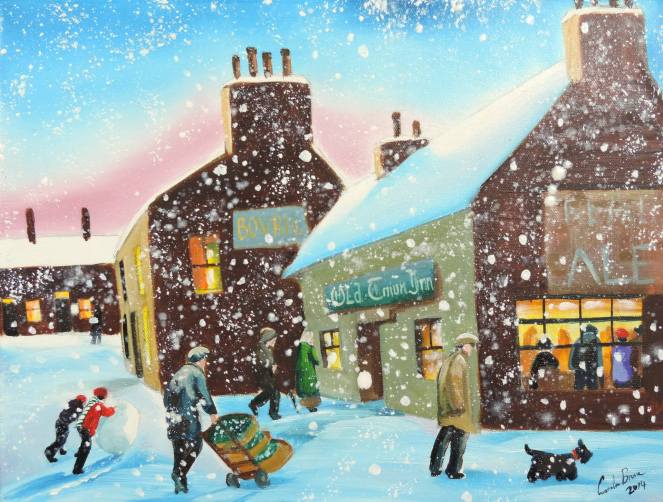

It was too late. The rebbe had already arrived at the nearest village. He headed straight down for a Cossack inn, and burst open the doors. The folk band stopped playing. The publicans looked up in stunned silence. The Jews huddled outside, expectantly looking in. The rebbe stretched out his hand.

Silence. A moment that felt like an eternity. Then, suddenly, a Cossack got up and took the rebbe’s hand. To everybody’s surprise, they began to dance. The band started playing again. Some of the students tentatively made their way into the inn. They, too, began dancing with Cossacks. Before long, all the Jews and all the Cossacks were dancing. This Purim party spilled out into the street. They danced all through the night until they could feel the veins in their feet pumping. They laughed until their bellies ached. They ate and drank and comingled until nobody could tell who was Jew and who was Cossack.

As the sun came up, the rebbe and his students fell about in a heap outside the pub, laughing. “That”, said the rebbe, “is how you blot out the name of Amalek. You see, Amalek is not a person. Amalek is the part of us that wants to trample the weak, just as Amalek did to Israel in the desert. Amalek is the part of us that wants to crush difference and secure power, just as Haman did to the Jews in Shushan. Amalek is any part, in any of us, that chooses hatred. The reason our sages told us not to turn to violence to blot out Amalek is because Amalek cannot be destroyed by violence; only by love. That is our weapon against hatred.”

This is a lesson we have to learn again and again, in every generation. When this week began, we woke up to the news of Muslims being killed at their places of worship in New Zealand. This week has seen yet more attacks on mosques. In Birmingham, a vandal took a hammer to the windows of several masjids across the city. The rise of the far right has spread to the Netherlands, where fascists have made significant gains and unseated the government.

We live in times when the violent attack the vulnerable; when hatred seeks out to take over; when diversity is under threat.

It is understandable that we should feel fear. It is righteous that we should feel anger. But we must also greet these times with an open and outstretched hand, willing to accept that a better world is possible, hopeful that people can change, faithful that we can drown out the impetus to hatred. We must be ready to dance. That is how we blot out the name of Amalek.