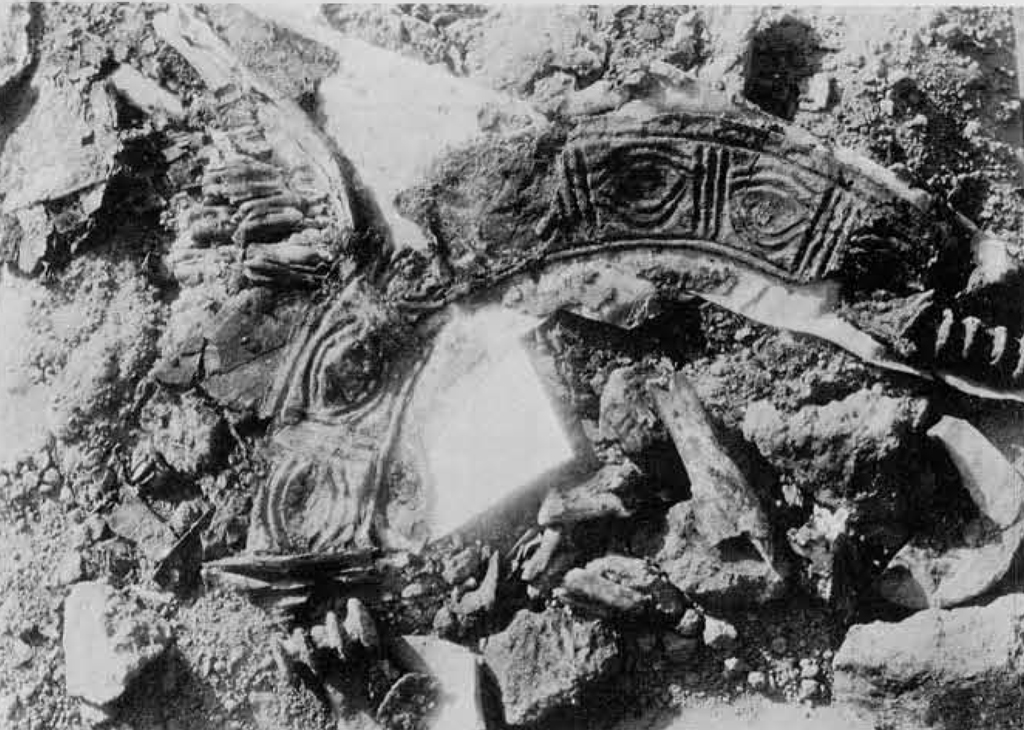

In 1922, archaeologists dug up a site in modern-day southern Iraq. There, they found incredible spans of gold and sophisticated armour, and Iron Age Sumerian artefacts, encased within stone walls. They dubbed this place “the Royal Cemetery of Ur,” an ancient Babylonian mausoleum.

On that site, they also discovered evidence of hundreds of human sacrifices. Among the human sacrifices, a considerable number were children.

Nearly all of the skeletons were killed to accompany an aristocrat or member of the royal family into the afterlife. Some had drunk poison. Some had been bashed over the head with blunt objects. After their death, many were exposed to mercury vapour, so that they would not decompose, but would remain in a lifelike posture, available for public display.

This site dates to sometime around 2,500 BCE in the ancient city of Ur. According to our legends, another figure came from the ancient city of Ur sometime around 2,500 BCE.

His name was Abraham.

In the biblical narrative, Abraham wandered from Ur to ancient Canaan, where he began to worship the One God, and founded Judaism.

The world in which Abraham purportedly lived was rife with child sacrifice. Across the Ancient Near East, archaeologists have uncovered remains of children on slaughtering altars. They have found steles describing when and why they sacrificed children. They have found stories of child sacrifice from the Egyptian, Greek, Sumerian, and Assyrian civilisations.

So problematic was child sacrifice in the ancient world that our Scripture repeatedly condemns it. The book of Leviticus warns: “Do not permit any of your children to be offered as a sacrifice to Molech, for you must not bring shame on the name of your God.” The prophet Jeremiah describes disparagingly how the Pagans “have built the high places to burn their children in the fire as offerings to Baal.” In the Book of Kings, King Josiah tears down the altars where people are sacrificing their children.

Abraham put a stop to the practice of child sacrifice. It seems to happen suddenly, and without warning, and with even less explanation. No reason is given why he abruptly ended all the cultural deference that had gone before and opposed an entrenched religious practice.

The question we now must ask is: why?

One reason that comes to mind is that it is so obviously immoral. Surely it should be self-evident that you don’t kill kids! But that wasn’t obvious to all the people around Abraham. And that wasn’t obvious to traditional commentators, either. In their world, the morally right thing was always to obey God.

A traditional reading says that Abraham stopped child sacrifice in obedience to God. In the story we read today, Abraham is called upon by God to go up on Mount Moriah and slay his son. Only at the summit, when he holds up his arm to murder Isaac, does God stop him, telling Abraham that he has proved his devotion to God by not withholding his son, and that he does not have to kill Isaac.

Yet there are several problems with this story. If we adhere to the traditional reading, God still wanted child sacrifice, and felt that doing so would prove Abraham’s devotion. In fact, nearly all traditionalist readers interpret it this way,saying that obedience before God should be a sacred virtue. A conservative reader of the Bible says that the moral of the story is that we should be subservient to God, and do what we are told.

God said not to perform child sacrifices, so we no longer do. That would mean, then, that if God had said child sacrifice was permitted, we would still be doing it.

In 2007, the Israeli philosopher Omri Boehm offered a radical reinterpretation of the story of the binding of Isaac. The story, Dr Boehm argues, is not about Abraham’s fealty to God, but his disobedience. Dr Boehm shows how, reading against the grain of traditional interpretation, this is not a story where God changes tact and decides not to ask for child sacrifices anymore, but where Abraham rebels against authority and refuses to commit murder.

For Boehm, what was truly radical about the Binding of Isaac was that it set out a new set of values, completely at odds with those of the Ancient Near East. Where other cultures practised child sacrifice because it was part of their established culture, Abraham resisted and put life above law. Where others encouraged obedience to authority, so much that poor people could be killed in the palaces of Ur to serve their masters in the afterlife, Abraham made a virtue of rebellion. For our ancestor Abraham, refusing to follow orders, even God’s, was the true measure of faith. By not killing, even if God seemingly tells you to, you show where your values really lie.

This is not a story about obedience, but rebellion. And that message – of resistance against authority in defence of human life – has much to teach us today.

Boehm reconstructs what the archetypal story of child sacrifice was in the Ancient Near East. Across many cultures and time periods, there was a familiar refrain to how the story went. The community is faced with a crisis: some kind of famine, natural disaster, or war. The community realises that its gods are angry. To placate the gods, the community leader brings his most treasured child and sacrifices him on an altar following the traditional rites. Then, the gods are pleased and the disaster is averted.

We can see that the biblical narrative clearly subverts the storytelling tradition that was around it. In other cultures, the community leader really did sacrifice his special child, and that really did please their Pagan god. In our story, the community leader does not sacrifice his special child, and the national God proclaims no longer to desire human sacrifice. This is already then, a bold message to the rest of the world: you might sacrifice children, but we will not.

Boehm takes this a step further and looks at source criticism for the text. Most scholars of Scripture accept that Torah is the work of human hands over several centuries. One of the ways we try to work out who wrote which bits is by looking at what names for God they use. Whenever we see the name “Elohim” used for God, we tend to think this source is earlier. Whenever we see the name “YHVH” used for God, we tend to assume the source is a later edit by Temple priests.

The story of the binding of Isaac is odd because it uses the name “Elohim” almost the entire way through, until the very end, when the angel of God appears and tells Abraham not to kill Isaac. That means that most of the text is from the early tradition and only the very end part, where the angel of God tells Abraham not to kill Isaac, comes from the later priests.

So, Boehm asks, what was the earlier version of the text? If you take out the verses where God is YHVH and have only the version where God is Elohim, what story remains?

Well, in the version that we know, where both stories are combined, an angel of God calls out and tells Abraham not to sacrifice Isaac. That’s the bit where God is YHVH. If you take that out, and have only God as Elohim, Abraham makes the decision himself. No angel comes to tell him what to do. Next, if we cut out the parts where God is YHVH, there is no praise from the angel, telling Abraham he made the right choice. Instead, you get a story where Abraham deliberately disobeys his God because he loves the life of his son more.

The earliest version of the text, before the Torah was edited and a later gloss was added, is one in which Abraham is commanded by God to sacrifice Isaac, goes all the way up Mount Moriah, and then refuses. Without prompt or praise from God, Abraham decides to sacrifice a ram instead of his son. In the earliest version of the biblical narrative, when source critics have stripped away priestly edits, God tells Abraham to sacrifice his son and Abraham rebels.

The earliest version, then, is an even more radical counter-narrative to the other stories of the Ancient Near East. Not only do we not sacrifice children. We also recognise that sometimes you have to say no to your god. In this version, rebellion is more important than obedience, especially when it comes to human life.

This isn’t just a modern Bible scholar being provocative and trying to sell books. In fact, Boehm shows, this was also the view of respected Torah scholars like Maimonides and ibn Caspi. These great mediaeval thinkers didn’t think of the Torah as having multiple authors, but they could see that multiple stories were going on in one narrative. One, they thought, was the simple tale of obedience, intended for the masses. But hiding between the lines was another one, for the truly enlightened, that tells the story of Abraham’s refusal.

Boehm terms this “a religious model of disobedience.” By the end of the book, you go away with the unshakable impression that Boehm is right. True faith, he says, is not always doing what you think God is telling you. Sometimes it is reaching deep within your own soul to find moral truth. Sometimes you really show your values by how you defy orders.

In his conclusion, Boehm takes aim at Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, an American religious leader, who lives in the West Bank settlement of Efrat. Rabbi Riskin had said, in his analysis of the binding of Isaac, that Abraham was a model of faith by his willingness to kill his son. Riskin insisted that he was willing to sacrifice his own children in service of the state of Israel.

This, says Boehm, is precisely the opposite of the message of the binding of Isaac. The point was not to let your children die. The point was to bring a final end to child sacrifice. The point was not to submit to unjust authority, but to rebel in defence of life.

Rabbi Riskin does not realise it, but by offering child sacrifice, he is really advocating for the Pagan god. He is describing the explicitly forbidden ritual of allowing your children to die.

Abraham thoroughly opposed these false gods who demanded ritual murder. They were idols; and child sacrifice a monstrous practice that we were supposed to banish to the past. The very essence and origin of Jewish monotheism is its thorough rejection of killing children.

Boehm could not have known how pertinent his words would become. This year has been one of the worst that those of us connected to Israel can remember. Beginning on October 7th, with Hamas’s horrendous massacres and kidnappings, the last Jewish year has seen us rapt in a horrific and seemingly never-ending war.

This year, thousands of Israelis were killed. This is the first time in a generation that more Israeli youth have died in war than in car crashes. Reading through the list of names, it is remarkable how many of the soldiers were teenagers.

That is not to even mention the 40,000 Palestinians whom the IDF have killed. According to Netanyahu’s own statements, well over half were civilians. Around a third were children. As famine and food insecurity rises, the risk of deaths will only accelerate. It has been agonising to witness, and I cannot imagine how painful it has been to live through.

Yet, during my month in Jerusalem, I saw that the voice of Abraham has not been extinguished. There are few groups I hold in higher esteem than the Israeli peace movement. Against untold threats and coercion, in a society that can be intensely hostile to their message, they uphold Abraham’s injunction against killing.

One of the leaders of the cause against war was Rachel Goldberg-Polin. On October 7th, her 19-year-old son, Hersh, was kidnapped by Hamas. His arm was blown off and he was taken hostage in Gaza. From the very outset, Mrs. Golderg-Polin argued fervently for a ceasefire and a hostage deal that would bring her son home. She warned that the only way her son would come home alive would be as part of political negotiations.

At the end of August, as Israeli forces neared to capture Hersh as part of a military operation, Hamas shot her son, Hersh, in the head.

Rachel Goldberg-Polin’s refusal to give up hope, refusal to sacrifice her son, and steadfast insistence on peaceful alternatives is a true model of Abraham’s faith.

And it involves serious rebellion too. When I met with hostage families in Jerusalem, I was shocked to hear how, for protesting against the war to bring their families home, they had been beaten up by Ben Gvir’s police. I saw this with my own eyes when I marched alongside them. People shouted and jeered at them, and the police came at them with truncheons.

In July, when I went with Rabbis for Human Rights to defend a village in the West Bank against settler violence, we were joined in our car full of nerdy Talmud scholars by a surprising first-timer. A strapping 18-year-old got in to volunteer in supporting the Palestinian village. What was most remarkable was that he himself lived in a West Bank settlement.

He explained that he had refused to serve in the military. He did not know that others had done it before, or that there were organisations to support Israeli military refusers. Instead, he said, he thought to himself: “if I don’t go, they won’t kill me; if I do go, I might kill someone.” What could be a truer expression of Abraham’s message: no to death! No to death, no matter the cost.

He really had to rebel. For refusing to serve in the war, the conscientious objector I met spent seven months in jail. Still now, there are dozens of Israeli teenagers in prison because they would not support the war.

Throughout my time in Jerusalem, I attended every protest against the war and for hostage release that I could. One of the most profound groups I witnessed was the Women in White, a feminist anti-war group going back decades. One of these women, with grey hair and the look of a veteran campaigner, held a placard that read in Hebrew: “we do not have spare children for pointless wars.”

Is this not exactly what Abraham would say? We will not sacrifice our children on the altar of war!

Theirs is truly the voice of Abraham, the true voice of Judaism. It is the voice that opposes child sacrifice. Theirs is the voice that upholds the God who chooses life.

Talmud tells us that, when we blast the shofar one hundred times on Rosh Hashanah, we are repeating the one hundred wails of Sisera’s mother when she heard her son had died. Sisera was, in fact, an enemy of the Israelites, who waged war on Deborah’s armies, and was killed by the Jewish heroine, Yael. Still, at this holy time of year, we place the grief of Sisera’s mother at the forefront of our prayers.

We take the cry of every mother who has lost a child and we make it our cry.

Thousands of years after the Sumerian Empire had ceased existing, archaeologists dug up its remains, and saw a society that practised child sacrifice. From the very fact of how they carried out murder and permitted death, the excavators could tell a great deal about what kind of society this was. One that killed people to serve their wealthy and their gods.

One day, thousands of years from now, historians may look upon us too, and ask questions about what our society was like, and what we valued. May we take upon ourselves the mantle of Abraham.

May they look back and say that we chose to value life. May they look back and see that our people despised death and war. May they look back on us and see a society that practised faithful disobedience.

Amen.