When they lived in Eden, Adam and Eve did not have to labour for their food. Yet, in the moment that they were expelled from paradise, God gave them stern instructions on what they would have to do.

God warned: “Through painful toil you will eat food from it all the days of your life. By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return.”

Where once they had a homeland, the original people were cast out into a state of permanent exile, to live in the world with all its struggles.

This fable, though mythic, tells us something true about how human beings came to have the life we do. While there was probably never really an original idyll where people lived without work, there was a moment, millennia ago, when humanity’s ancestors shifted how they lived.

For most of our history, we had wandered. All people were nomadic. They hunted and gathered, migrating between caves and carrying temporary shelters all over the neolithic continents.

Then, as the last Ice Age ended, around 11,000 years ago, people discovered that they could store seeds from one year to the next. They developed agricultural systems, with plots of land dedicated to growing crops. Having once roamed the earth, they could stay put in a single place, which would be their land.

Cain and Abel are archetypal characters who tell us about this great change. Abel was a nomad, who herded flocks and grazed them over the hills. His name means “breath” or “waif” – for, like a cloud that drifts across valleys, he wafted without leaving a trace. He was a symbol of the old way of constant movement.

Cain, his brother, had a name which meant “acquire” or “possess.” Just as God had warned his parents when they were cast out from Eden, he worked by the sweat of his brow. He laboured on the soil, where he sowed, grew, and harvested plants for food.

At the dawn of civilisation, these were the two types of people: those who cultivated the land in fixed places; and those who travelled with no fixed abode. Everything that was movable, like herds and clothes, was held by the nomads, the Abels. Everything immovable – like allotments and orchards – was owned by those who settled, the Cains.

Our Torah says that God favoured Abel over Cain, and it probably felt that way. While agriculture can keep people settled and build lasting cultures, it is unpredictable. One bad year of too much rain, or not enough, or bad seeds or infertile soil, can leave an entire community famished and ruined.

A pastoralist, on the other hand, has a tough but durable existence. The life of a shepherd means much moving, but that is part of what makes their life sustainable. Sheep can be moved to wherever water is healthy and available. A goat can graze on thistles and other crops that people find inedible.

So, yes, to the ancient mind, it may have seemed like God looked more kindly on the one who wandered than the one who farmed.

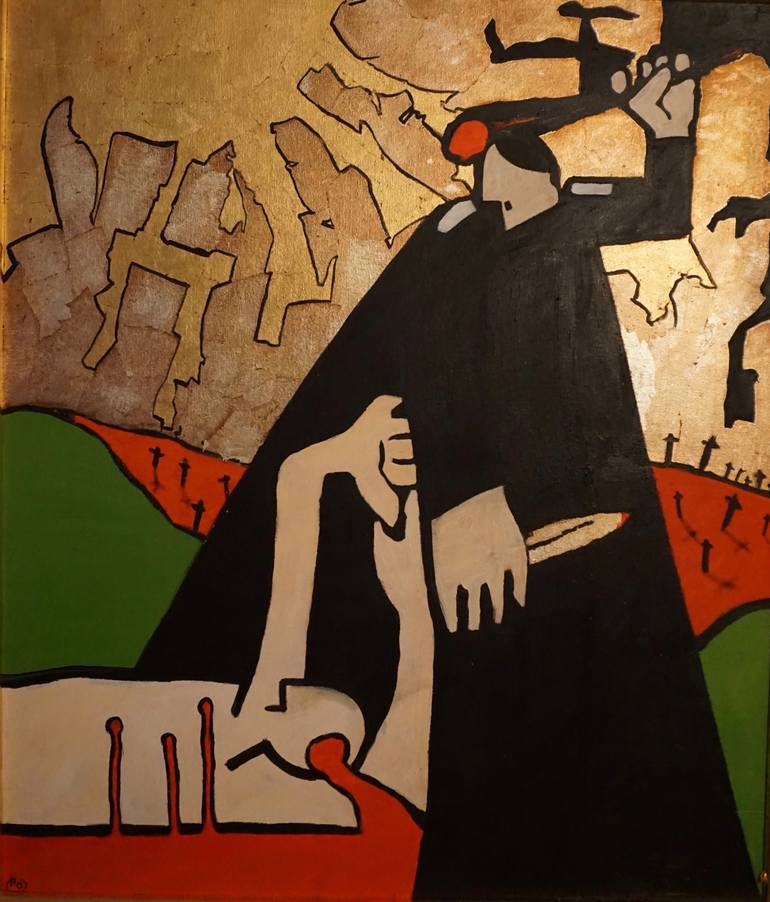

Cain killed Abel.

The one who tilled the land and made it his home sought to destroy that wandering waif. Perhaps, indeed, he did. Perhaps the founders of the earliest civilisations enforced their new way of life with violence and coercion.

But not successfully. As soon as Cain commits the first murder, God tells him what he will become. Cain cries out at his punishment: “Today you are driving me from the land, and I will be hidden from your presence; I will be a restless wanderer on the earth, and whoever finds me will kill me.”

For killing Abel, Cain would become Abel. Having been the acquirer, he would take his place as a nomad. Having been so sure in his farmland, Cain would return to the ancient ways of roaming.

God said to Cain: “Abel had no homeland. Now neither do you. Abel was forced to wander. Now you will wander too.”

Generations passed, but the draw of homeland was irresistible. In ancient Mesopotamia, Abraham was called “ha-ivri” – border-crosser; the one who passed between places.

He heard the voice call out: “Go, get going, to a land that I will show you,” and Abraham traversed to Canaan, to a new land where he hoped he would settle.

He took his family, and his possessions, his movable goods that had sustained him in all his wanderings, and went in search of home.

But, having reached the land that God would show him, he saw it and he left. He pitched his tent and built an altar, then carried on to Egypt. When he returned, he did so as a nomad, travelling with his flocks, threatened by the Canaanites and Perizites who had acquired the land, as Cain had once done.

Abraham sought a home, and found one, but it was never a permanent space. He had wandered to be in one place, but in that one place, he found he had to keep on wandering.

Abel, Cain, and Abraham all wandered. So did the Israelites in the desert. Deep in our ancient stories, there is an idea that, while a settled home may be desirable, migration is part of the human experience. We may dream of Edens, but life is unpredictable, and fortune may force us to move.

In Torah stories, we learn the survival of migrants, passed down from generations who knew what it meant to move with the seasons.

It is a deep knowledge, from before we were Israelites or even Jews, stretching back to our history as neanderthals.

Please do not imagine that I am romanticising exile. Travelling breeds resilience and creativity, but it is far from idyllic.

Instead, wandering is an inevitability.

In every community and in every family, if you go back far enough, you will find a traveller. In the stories of our Torah, you learn that it could be you.

Abel was a restless nomad, and we may wander too.

Shabbat shalom.

I learnt this Torah from Rabbi Joel Levy at the Conservative Yeshiva in Jerusalem.